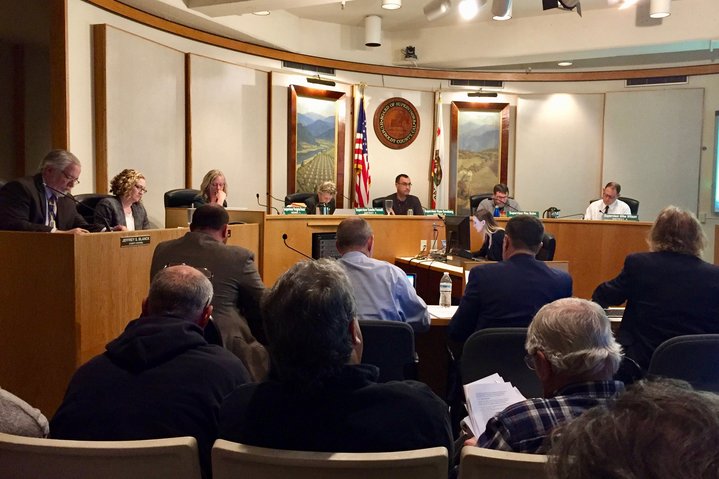

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors met Monday to start deliberating on the proposed Commercial Cannabis Land Use Ordinance.

On Monday morning, when Humboldt County Planning and Building Director John Ford presented the Board of Supervisors with a comprehensive new set of proposed weed regulations, he called it “literally a gift,” one that came “with a bow wrapped around it.”

It almost sounded like he was telling the board they didn’t need to do anything but vote up or down on the policy measures that had already been developed by the Humboldt County Planning Commission. He told the board that the commission had done “some very heavy lifting” over the course of 13 public meetings, and what they’d come up with was “really a complete proposal.”

Seeking to refute claims that the process has been rushed, Ford recounted the public process that led up to yesterday’s hearing, a process that included numerous workshops, 20 public meetings and a variety of consultations with local cities and tribes.

Yurok Tribal Heritage Information Officer Frankie Myers addresses the board.

But the public comment period at yesterday’s meeting proved that locals still have plenty to say about how the county should regulate the marijuana industry here in the most famous weed county in the world.

Roughly three dozen people got up to address the board (a few more than the 30 we erroneously reported yesterday), and they represented a wide variety of perspectives — from Fortuna officials who want pot gardens kept as far away from their city as possible to weed entrepreneurs hoping the county rules will maximize their competitive advantages.

The ordinance itself, which was released on Friday and totals more than 2,000 pages, including the Final Environmental Impact Report (FEIR), would allow a major expansion of legal cannabis activities countywide. For example, it would reopen the permit application period and, if a separate resolution is approved, establish a cap on the number of cultivation permits and total acres of growing area — 5,000 permits or 1,250 acres, whichever comes first.

The ordinance would also allow cultivation to take place in more places across the county’s unincorporated areas, not just on prime agricultural soils. It would allow existing grow sites to expand, encourage cannabis support facilities, create new permit types (including one compatible with the state’s flexible microbusiness license) and allow permit holders to run multiple activities, such as “canna-tourism,” weed farm stays, farm-based retail sales and pot-themed special events.

The new rules would allow for a maximum of four cultivation permits per applicant, and the biggest weed garden allowed on a single parcel would be eight acres. And the Planning Commission created an incentive measure in hopes of bringing more growers into the fold of legalization: Any applications to permit existing grow operations that the county receives by Dec. 31, 2018 would be processed at 100 percent of the current size of the grow. Same goes if the applicant hopes to take advantage of the county’s Retirement, Remediation, and Relocation (RRR) program. Any applications received during 2019 would be processed at just 50 percent of the current size of the grow, and any received after that would either need to comply fully with the new ordinance or be considered a new cultivation operation.

A couple of more controversial measures in the Commercial Cannabis Land Use Ordinance (CCLUO) received a good deal of public comment. Those were the removal of a 600-foot setback requirement from school bus stops for weed activities, and a discretionary permit requirement for any marijuana business asking to locate within a local city’s “sphere of influence.”

That latter proposal is of particular interest to the residents and leaders of Fortuna, a city that has decided it wants nothing to do with any of this weed business. Following Ford’s two-hour rundown of the policy specifics in the CCLUO, Fortuna Mayor Sue Long got up to address the board. She objected to a proposal that would allow cannabis businesses to apply for discretionary permits if they’re within 1,000 feet of city limits, aka the “sphere of influence.”

“We’re asking for no permits in the sphere of influence,” Long said. She acknowledged that city leaders didn’t give enough input early in the process, but she said the bottom line is that Fortuna has considered its position on marijuana and decided, “We just don’t want any.”

Fortuna City Manager Mark Wheetley seconded Long’s comments, adding that areas within the city’s sphere of influence may eventually be annexed. He also suggested that the county take a second look at the environmental impact report with an eye toward “sustainable water management.”

Environmental concerns were a running theme during public comments, starting even before the meeting.

Tribes and conservationists held a press conference outside the courthouse at 8:30 a.m., half an hour before the meeting started. Scott Greacen, conservation director for Friends of the Eel River, said county leadership facilitated the green rush, allowing it to grow to an unsustainable and irresponsible size.

“Realistically what we’ve got to do at this point is radically downsize” the industry, Greacen said. “From our perspective the absolutely key thing is we have got to protect the watersheds that are critical to keeping salmon and steelhead going in Humboldt County but also on the North Coast.” The key to that, he added, is not so much in regulations but rather the environmental analysis, with watershed-specific data.

As for the proposed 5,000-permit cap on cultivation, Greacen said it’s meaningless. “It’s complete bullshit. They’ll never get 5,000 permits.” He said the local industry can’t support that many growers, and even if it could the county couldn’t effectively regulate them. “If you’ve got three or six county code enforcement people, there’s no way you’re going to meaningfully regulate 500 permitted operations, much less the 5,000 we’re talking about now,” Greacen said.

Craig Tucker, the Karuk Tribe’s natural resources policy advocate, echoed Greacen’s call for a watershed-by-watershed environmental analysis, saying that’s what’s necessary if the county wants to create a cannabis industry that’s good for both the economy and the environment. “Right now it’s destroying fish, and it’s killing water quality,” Tucker said.

And Frankie Myers, the heritage information officer for the Yurok Tribe, said he wanted to inform the supervisors that certain watersheds within the tribe’s ancestral boundaries serve as their culture’s church and school. “This isn’t a cannabis issue for the tribe; this is an extractive industry issue,” Myers said.

As for those directly involved in the cannabis industry, they, too, had suggestions for how the ordinance could be improved.

Bruce Ayers, owner of Southern Humboldt Concentrates, said the county needs to focus less on permitting growers, who are abundant, and more on other steps in the supply chain, including cannabis manufacturing and distribution. He said outdoor-grown weed is selling for $500 a pound and being considered biomass. “The cultivation permit you issued me is worth nothing unless I’m able to manufacture it into something of value,” Ayers said.

Others complained about the “bureaucratic red tape” involved in complying with state and local regulations.

Alex Moore of Honeydew Farms said his company has received 30 state licenses, and he urged the board to remove the proposed limit of four one-acre cultivation permits. Noting that local growers are competing against people whose counties have no such caps, Moore said, “Don’t limit a company’s ability to grow into a large statewide brand.”

Bus stop setbacks were also a topic of some discussion. While the Fortuna contingent argued in favor of the previous ordinance’s 600-foot setback requirement, Ian Herndon of Humboldt Boutique Gardens cried foul. After investing tens of thousands of dollars into his business it was stopped in its tracks by the sudden appearance of new bus stops, he said. And he argued the setback requirement doesn’t make sense for indoor grows or manufacturing operations because their operations remain obscured to passers-by.

Fourth District Supervisor Virginia Bass seemed to validate Herndon’s complaints later in the meeting when she observed, “There do seem to be several pop-up bus stops happening.”

Terra Carver, executive director of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, offered a list of policy suggestions, including raising the size limit on operations considered “artisanal” from 3,000 square feet to 10,000 square feet, and she urged the board not to change any conditions of approval for applicants located within the spheres of influence of local cities.

It was clear from both the volume and tenor of the public comments that people in the industry are feeling uneasy. In fact, one man, SoHum resident Mark Richard, said he’s been having panic attacks. Growers are downright scared to hear about pounds selling for as low as $300, he said. “It would be a shame to see this industry go away,” he added.

After nearly two hours of public comment, Board Chair and Fifth District Supervisor Ryan Sundberg said, “The good news is we’re not gonna pass this today.”

The supervisors directed staff to bring back a range of options to consider for both the cultivation permit cap and bus-stop setbacks.

And here’s an important takeaway: The public comment period for this ordinance was extended to March 28. Comments can be sent to Director John Ford (jford@co.humboldt.ca.us) or your county supervisor.

The public hearing was continued to April 10 at 1:30 p.m.

CLICK TO MANAGE