The Klamath River past the J.C. Boyle Dam, one of four Klamath hydroelectric dams owned by PacifiCorp, along with Iron Gate, Copco I and Copco II. | Photo: Bobjgalidno, GNU free documentation license, via Wikimedia Commons.

The past 15 years have seen a lot of complex negotiating, arguing and legal wrangling over the Klamath River Hydroelectric Project. For the most part these disputes have been limited to the fate of the four PacifiCorp-owned hydroelectric dams on that waterway.

Not to minimize the stakes there: If the decommissioning goes through as planned (the latest timetable aims for a drawdown sometime in 2021) it will be the largest dam removal project in U.S. history, with major implications for environmental restoration, the salmon fishery, agriculture and local tribes.

But a recent Federal Appeals Court decision is having repercussions that extend far beyond the Klamath River Basin. It’s the result of a legal fight between the Hoopa Valley Tribe and partners in the landmark Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA).

Both sides in this dispute want the dams to come down, but they have long disagreed on the best methods to achieve that end. Hoopa wants to fight PacifiCorp; the others want to work with the dam owner.

Hoopa says the recent court ruling did away with an illegal loophole that was allowing states to hold federal proceedings hostage for years on end. Opponents say the verdict has thrown a wrench into state and tribal efforts to protect the environment, and could have devastating repercussions across the country.

The D.C. Circuit panel’s ruling, issued this past January and upheld under appeal in April, concerns the environmental oversight authority states have under the Clean Water Act.

Critics of the decision, including California, Oregon and more than a dozen other states, plus major environmental groups and several tribes, believe it was deeply misguided. They argue that it not only threatens the prospect of dam removal on the Klamath but also strikes a blow to states’ environmental oversight authority on federally permitted dam and pipeline projects.

In effect, they say, this decision means that license-holders for dozens of dams affecting hundreds of miles of rivers may no longer have to comply with state water laws. The three environmental groups that appealed the January ruling — American Rivers, Trout Unlimited and California Trout — must now decide whether to appeal the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, an attorney for the Hoopa Valley Tribe, which filed the suit against the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), among other defendants, says this ruling brought an end to an “egregious” and illegal bureaucratic stalling tactic that long stood in the way of the tribe’s own dam removal efforts.

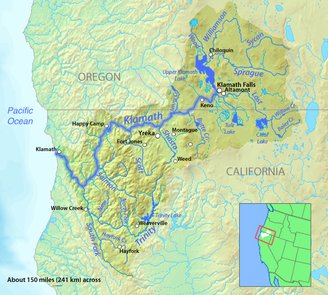

Map of the Klamath River watershed. | Wikimedia Commons.

The case revolves around Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, which says a federal agency can’t issue a permit or license for any project that might result in discharge into U.S. waters — projects such as hydroelectric dams and pipelines — until the states or authorized tribes where that water will be discharged get a chance to review the water quality impacts.

The statute gives states and tribes “a reasonable period of time (which shall not exceed one year)” to either issue or deny a water quality certification. In practice, however, states often take much longer.

For example, as part of the 2010 Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA), the signatories, including PacifiCorp, the state of California, the state of Oregon, the Karuk, Klamath and Yurok Tribes, plus various counties, irrigation districts and nonprofit groups, repeatedly asked FERC to defer that one-year statutory limit. The parties were buying time to negotiate details of the agreement and, they hoped, convince Congress to pass legislation implementing it.

To achieve this delay the parties asked FERC to allow PacifiCorp to periodically withdraw and resubmit their 401 water quality permit application before the California State Water Resources Control Board. Each time they did this it reset the clock on that one-year deadline, giving the parties another year to work with.

Environmental groups, FERC and others say this tactic of withdraw-and-resubmit is exceedingly common.

“For simple projects with complete applications, one year is ample time to make a decision,” reads a statement from the Hydropower Reform Coalition issued earlier this year. “However, in circumstances where the project is complex or the application is incomplete, additional time is often required by a certifying agency to develop the record.”

The environmental protections at the state level, particularly those in the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), often require more extensive mitigation measures than those imposed by FERC.

The Hoopa Valley Tribe disapproved of this approach, as they’ve done before on Klamath dam matters. The tribe was not a signatory to the KHSA or the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA). They felt the terms of the deal wouldn’t provide sufficient water in the lower Klamath to support fish populations, and they doubted that Congress would ever pass legislation to implement the agreement.

The latter doubt, at least, proved justified. The KBRA expired in 2015 due to inaction in the U.S. Congress.

“Hoopa was always opposed something that would delay dam removal, such as the original KBRA,” the tribe’s attorney, Tom Schlosser, told the Outpost. Instead, he said, the tribe wanted FERC to proceed with relicensing the dams because they believed any new license would require PacifiCorp to provide volitional fish passage, per the Federal Power Act, and the only way to achieve that would be dam removal.

From Hoopa’s perspective, the withdraw-and-resubmit tactic stood in the way of bringing down the dams. So in 2012, Hoopa asked FERC to declare that by failing to act within the one-year timeframe spelled out in Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, California and Oregon had effectively waived their authority, relinquishing their right to impose water quality standards.

FERC denied the request, and so in 2014 Hoopa filed a lawsuit in the Circuit Court of Appeals. The case of Hoopa Valley Tribe v. FERC, et al. wended its way through the court system, eventually resulting in January’s Circuit Court ruling in Hoopa’s favor.

The three-judge panel found that California and Oregon were, in essence, holding federal licensing of the Klamath dams hostage. “By shelving water quality certifications, the states usurp FERC’s control over whether and when a federal license will issue,” the ruling says.

The court found that the “coordinated withdrawal-and-resubmission scheme,” as the decision called it, has no legal basis. “Accordingly, we conclude that California and Oregon have waived their Section 401 authority with regard to the Project.”

Schlosser said the ruling was a vindication for the Hoopa Valley Tribe. “By showing that the withdraw-resubmit process was illegal we removed an obstacle to dam removal,” he said.

Others don’t see it that way. Steve Rothert, California director with American Rivers, said the premise underlying Hoopa’s lawsuit — that FERC will be forced to order dam removal — is fundamentally flawed.

“FERC, in its history of issuing hydropower licenses, has never once required a dam owner to remove a dam against its will,” he said.

Rothert thinks it’s more likely that the decision will backfire, causing PacifiCorp to reconsider dam removal altogether. The company’s duty, he said, is to its shareholders alone.

“By forcing this case, [Schlosser] has removed one of the most important economic levers in PacifiCorp’s business decision [to remove the dams], which is, ‘How will the cost of complying with California and Oregon water quality conditions … affect the bottom line of this project?’” Rothert said.

To date PacifiCorp has not indicated that it plans to back out of the dam-removal agreement. Indeed, last month the company entered into an agreement with Kiewit Infrastructure West Co. giving the firm site access to conduct initial surveying and other work for the planned removal of those four dams.

Regardless, the larger implications of the ruling may lie elsewhere.

Schlosser believed the decision would be interpreted narrowly, in part because the parties in the Klamath alliance had a formal, written agreement regarding the withdraw-and-resubmit routine, whereas most other projects utilize the tactic without such documentation. But the case is being treated as precedent, a means by which project applicants can get out from under state environmental review on dam and pipeline projects scattered across the U.S.

It’s being called the “Hoopa exemption,” and licensees across the country are asking for it. Thus far, FERC has been amenable to granting it.

In February, for example, the Placer County Water Agency cited the Hoopa Valley decision as it asked FERC to declare that the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) had waived its certification authority for relicensing of the Middle Fork American River Project.

Placer County had been utilizing the withdraw-and-resubmit technique, at the direction of the water board, since 2012. On April 18, FERC granted the request, using the Hoopa decision as justification. “The Hoopa Valley court did not in any way indicate that its ruling was limited solely to the case before it,” FERC wrote.

Another project: The Nevada Irrigation District, in California’s Nevada County, cites the Hoopa Valley decision in asking FERC to waive the state’s 401 certification for the Yuba-Bear Hydroelectric Project in the northern Sierra Nevada. That decision remains pending.

Last month, PG&E also cited the Hoopa Valley decision in asking FERC to declare that California had waived its 401 authority over the Killarc-Cow Creek Hydroelectric Project in Shasta County. PG&E wants to proceed with decommissioning that project without having to comply with conditions from the state.

Elsewhere, Fortune 100 energy corporation Exelon is trying to get out from under the State of Maryland’s 401 authority over its Conowingo Dam Projects. According to a post in the National Law Review, Maryland’s 401 certification, issued on April 27, 2018, “imposes significant requirements for Exelon to remove itself or pay to have removed the phosphorus and nitrogen that flow from upstream on the Susquehanna River, at a cost of up to $7 billion over the term of the new FERC license.”

Exelon has asked FERC to declare that Maryland waived its 401 authority, per the Hoopa Valley decision, by directing it to withdraw and resubmit its application. That petition also remains pending before FERC.

And in April, FERC relied on the Hoopa Valley case in refusing to overturn its own prior decision that the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation had waived its 401 authority for a gas pipeline project in Pennsylvania and New York.

As noted on the Law360 blog, “FERC acknowledged that it had previously allowed a Section 401 permit applicant to withdraw and resubmit its application, but it said the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Hoopa Valley Tribe casts doubt on whether withdrawal-and-resubmission arrangements are still viable.”

Environmentalists are keeping tabs as more and more licensees cite the Hoopa Valley case in an effort to sidestep state oversight.

Ron Stork, senior policy advocate with Friends of the River, called the circuit court decision “the nightmare we all predicted — except Hoopa. It threatens the whole underpinning of the states’ ability to meaningfully participate in relicensing of FERC jurisdictional hydroelectric projects.”

Stork said FERC “absolutely hates” that states and some tribes have a meaningful role in the relicensing process, and so the agency will seize every opportunity to undermine that oversight.

“Essentially FERC views its job as being an advocate for licensees,” he said.

Stork said this decision couldn’t have come at a worse time, given the influence of the Trump administration.

Here’s why: States and tribes aren’t the only environmental watchdogs on pipeline and hydroelectric dam projects. Federal agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service also have significant input on the relicensing process.

“So we’ve historically had a state team working with federal agencies to improve the project conditions for recreation or fisheries, and FERC and the licensee on the other side trying to minimize cost and maximize profits,” Stork said.

But under the Trump administration, he said, the federal natural resource agencies have more or less switched sides; they’re working as advocates for the licensees rather than environmental protectors. “So the only player that has a meaningful ability to affect FERC are the states,” he said. “That is exclusively and only through their ability under the federal Clean Water Act to issue or deny or set conditions on water quality certifications.”

When courts find that states have waived their authority it means there may be no state-level environmental review until the project is up for relicensing, which could be as long as 50 years.

‘This is a huge deal gone terribly, terribly wrong, and it couldn’t have come at a worse time.’ —Ron Stork

“So you’re taking the state out of the game for perhaps half a century,” Stork said. “This is a huge deal gone terribly, terribly wrong, and it couldn’t come at a worse time.”

Other environmental leaders are equally appalled. “The implications are as great as we had feared,” said Chris Shutes, FERC projects director for the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance. He said that Hoopa’s approach in this case, challenging a common if perhaps rule-bending method of operating, should serve as a cautionary tale.

“To open the door to wholesale change to how business is done and to legal interpretation, that’s a very dangerous way to do business,” Shutes said. “Because once you throw it out there you don’t have control.”

Schlosser said this interpretation is incorrect.

“It’s absolutely wrong that this [decision] prevents the states from exercising their authority to protect water,” he said. “Section 401 requires states to approve or deny within a year. We’ve said all along, and we still say: all states have to do is deny the application.”

That’s exactly what’s happening now.

“California has begun to routinely deny 401 applications in hydropower licensings without prejudice even as to applications it has previously deemed complete, in order to attempt to extend the one-year process,” attorneys from the firm Van Ness Feldman, LLP, noted on The National Law Review.

Rothert, with the nonprofit American Rivers, said that may be fine for projects moving forward, but there are “dozens and dozens” of hydropower dam and pipeline projects that utilized the withdraw-and-resubmit tactic.

“This was the standard practice agencies used,” he said. And leaving all the authority to protect water quality in the hands of FERC would be dangerous.

“We do not consider FERC adequately committed to protecting the environment,” Rothert said. “Their job is to license hydropower projects. Their perspective is not one of river protection or enhancing tribal welfare.”

Schlosser said the parties in the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement should have thought about that sooner.

“It’s not as though they did this [withdraw-and-resubmit tactic] without regard to possibilities of its effect elsewhere,” he said. “They chose to block the Klamath proceedings on an illegal basis, and the fact that they jeopardized some deal made elsewhere … is not my concern.”

The three appellants in the Hoopa Valley case, including American Rivers, have until late July to decide whether to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. Rothert said they’ve been approached by a coalition of more than 20 states asking them to consider doing so, and at least five tribes are organizing for the cause as well.

CLICK TO MANAGE