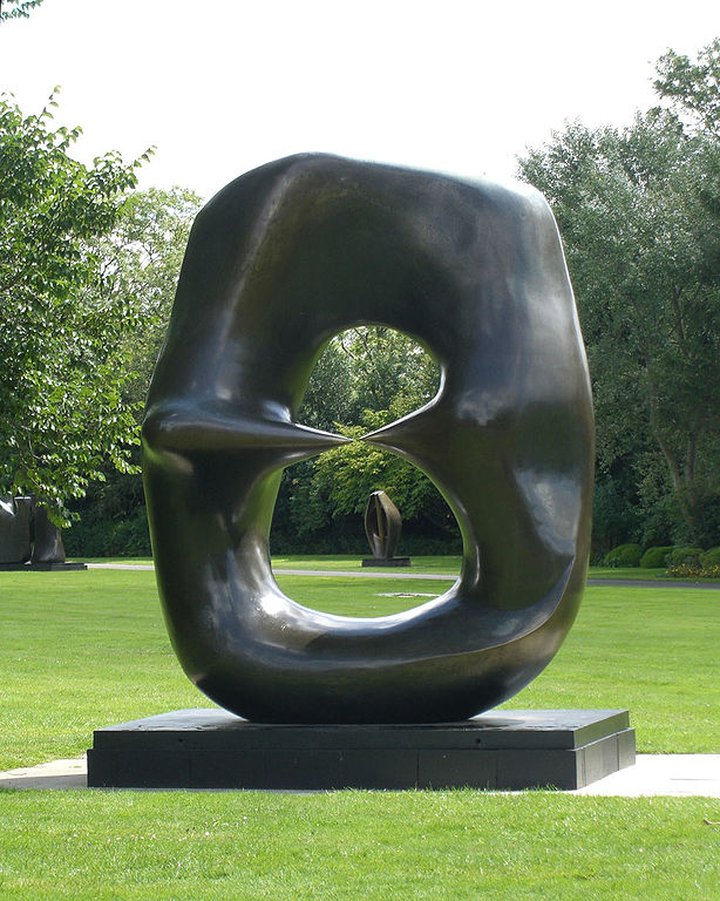

All non-obvious artistic creations — Joan Miró’s enigmatic paintings, Bach’s complicated variations on a single theme, Haruki Murakami’s nutty fantasies, Henry Moore’s perforated bronzes — demand that the audience meets the artist halfway. As viewers/listeners/readers, we are obliged to fill in the many gaps, interpreting what we’re seeing, hearing and reading, so that the experience becomes unique for each of us.

Henry Moore’s “Oval with Points.” (Reguiieee, public domain)

This is nowhere more obvious than with my secret vice: graphic novels. (Don’t call them “comics!”) In the best of them — Sandman, The Unwritten, Preacher, Watchmen, Lucifer, 100 Bullets (aficionados can add what I’ve missed) — the reader does half the work. So, while my wife is watching a British drama series on her iPad, I’m sipping my late-evening Jaegermeister, devouring a cool graphic novel, filling in the action between each panel, creating in my mind what the writers and artists haven’t shown, hearing the voices, making it my own. And thereby making the outrageous yarns (God’s gone missing! Moby Dick’s real! “Death” is a Goth chick! Lucifer…don’t get me started) all the more enjoyable.

It’s really a throwback to my childhood self from nearly 70 years ago, growing up in a provincial town outside London, England. Legend has it that pubs were empty and streets deserted in 1950s Britain on Mondays at 7.30 p.m., when BBC radio aired Journey Into Space (said in a spooky monotone with sounds of a rocket engine in the background). The original 18-episode series (Operation Luna) attracted more listeners than folks watching TV — the last time radio logged a larger audience than the tube. Eight million people listened to the final episode, out of a total population of fifty million.

Andrew Faulds as Captain Jet Morgan on the cover of the Radio Times, December 5, 1954. Faulds later became a Member of Parliament, famously referring to one fellow MP as “an honourable shit” and another as “a fat-arsed twit.” (Wikipedia: low-res, fair use)

Journey

Into Space, which was translated into Hindustani, Turkish and 15

other languages, was thought to be lost in space, as it were, for all

time, due to the BBC policy of erasing tapes (for reuse) three months

after broadcast. In a lucky break, misfiled transcription discs

turned up in 1986, and today you

can listen to the show that fired this 11-year-old

kid’s imagination. (And that of Stephen Hawking and countless

others.) It was all done live, with an eight-piece orchestra in the

studio. Check out the cool sound effects from 1953, if nothing else.

If you have an hour or three, buy me a cup of coffee and I’ll tell you, in excruciating detail, the layout and controls of the first rocket ship to land — in 1965 — on the moon. “Luna” was manned by three intrepid Englishmen and an Australian (“Strewth, cobber!”), in what passed for “diversity” in those days: think Kirk-Spock-McCoy-Scotty, absent visuals. I can also describe to you (series two: The Red Planet) the layout of the pyramid city of Lacus Solis in Mars’ Argyre Desert and how “conditioned” kidnapped Earthlings were able to breathe the thin Martian atmosphere; and (for a second cup) how Jet Morgan and crew thwarted the Martians’ dastardly plan to invade Earth (series three: The World in Peril). It’s all here in my head.

My point with all this nostalgia: had Journey into Space been a TV series, I wouldn’t have been able to describe a fraction of the detail that’s lodged so clearly in my mind over 60 years later. Same with other radio plays of the time, although JiS was a standout, ask any white-haired limey. The fact that we, the listeners, had to fill in all the visual details from our own imaginations is what made those details vivid and memorable.

OK, so Journey Into Space wasn’t exactly high art or even cutting-edge science (the writer, Londoner Charles Chilton, said in an interview before his death in 2013, that “my pursuit of astronomical studies is clumsy and very amateurish”). But the fact that Chilton’s flights of fantasy were presented blind, as it were (one entire episode took place in total darkness!) meant that it was up to us, the listeners, to provide the visuals. In spades.

Are you sure you don’t want me to describe the canals of Mars for you?

CLICK TO MANAGE