UPDATE, March 7, 3:28 p.m.: The Coastal Commission voted yes. Read about it here.

# # #

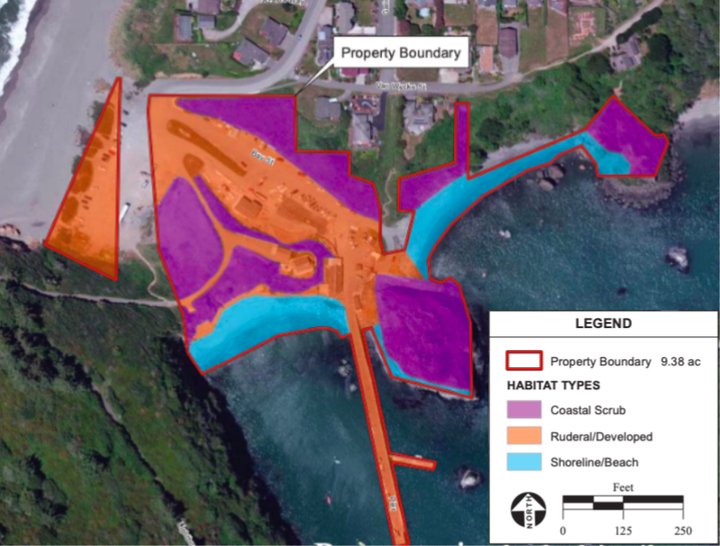

The site for the Trinidad Rancheria’s proposed interpretive visitor’s center, near Trinidad Harbor and the pier, is currently home to a tackle shop, a storage shed and facilities for boat cleaning and maintenance. | Photo from a Coastal Commission staff report.

Almost two decades ago, the Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria purchased nine parcels along the Trinidad Harbor waterfront — 10 acres of land that includes the Seascape Restaurant, the pier, a rental home, Launcher Beach (where, as the name suggests, boats enter the harbor), a parking lot and plenty of open space.

Now, the Trinidad Rancheria wants that property placed in federal trust status, a legal maneuver that would effectively remove the land from the State of California, the County of Humboldt and the City of Trinidad for administrative (and property tax) purposes.

The federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) encourages tribes to do this, saying, “[a]cquisition of land in trust is essential to tribal self-determination.” Sovereign tribal nations shouldn’t be bound by state and local regulations, the thinking goes.

By placing lands in federal trust, tribes also get access to grants for housing and energy-development projects, among other benefits. The Trinidad Rancheria says it “wishes to keep the land in trust for future generations.” It also intends to complete a stormwater improvement project and build a 1,300-square-foot visitor center on the property.

The BIA has already conducted an environmental assessment and determined that the project is consistent with agency regulations, and on Thursday the matter goes before the California Coastal Commission. Why does the Coastal Commission have any say over the matter? Because of the federal Coastal Zone Management Act, which requires that any federal activities affecting coastal resources be as consistent as possible with state management policies.

The commissioners are likely to get an earful. Indeed, they’ve already received more than 100 pages of written correspondence opposing the project.

The Rancheria’s pursuit of federal trust status for this scenic and much-used property has inspired intense push-back from a variety of directions, including local kayakers and other beachgoers who worry that the Rancheria might block public access, plus others who say the move could lessen environmental protections and limit public input on development projects.

The project has also inflamed long-standing grievances between local tribal entities, provoking the ire of both the Tsurai Ancestral Society and the Yurok Tribe, both of which dispute the Rancheria’s claims to what they say is their own ancestral territory.

In an outraged letter to the commission sent late last week, Yurok Tribal Chairman Joseph L. James called the proposal “distressing, deeply offensive, and wholly inappropriate.” He specifically challenged the Rancheria’s ancestral claims to the land in question. Members of the Trinidad Rancheria have ties to the Yurok, Wiyot and Tolowa tribes, according to their website.

“While the Rancheria may indeed have a few members with some Yurok ancestry,” James says in his letter, “the same can be said for dozens of tribes spread across the country due to intermarriage among various tribal communities. That fact does not give those tribes, nor the Rancheria, any right to trust land within another Tribe’s jurisdiction.”

The Yurok Tribe also objects to the Rancheria’s plans for an interpretive visitor center “within Yurok Ancestral Territory,” and James says in his letter that the Tribe “demands” that former Humboldt County supervisor and Trinidad Rancheria member Ryan Sundberg, who is participating in his final meeting as a Coastal Commissioner this week, recuse himself from the decision due to a conflict of interest.

The Tsurai Ancestral Society, a nonprofit whose members are direct descendants of the Tsurai Village, a Yurok settlement that was located in present-day Trinidad, raised many of the same objections. In a letter to the Coastal Commission dated Feb. 27, the society’s chairman, Axel Lindgren III, voiced deep concerns over the project’s proximity to sacred burial grounds, and to the Rancheria’s ownership of the nine parcels in question.

“The parcels were previously held in fee by a private individual who took them from the Tsurai inhabitants through the Homestead Act of 1862,” Lindgren said in Feb. 20 letter to the commission. “To separate us from our village through placing pieces of it into trust, with anyone other than the Yurok Tribe, is denying us our rights to practice our religion, ceremonies and traditional ways of our culture that are strongly tied to the land itself.”

The letter sent last week has an even more urgent tone.

“The Tsurai were able to withstand the push from extermination of their existence by the California Governor, and by local vigilantly [sic] groups,” it says. “We have been able to maintain a solid, unbroken connection to our village as we never left.” The Rancheria’s proposals, Lindgren suggests, represent an existential threat to his people. “The Tsurai may have been able to outrun the vigilantes, but the knife of another tribe putting our sacred places into trust is the one that will cut our throat.”

Most of the general public’s objections to the project stem from concerns over public access and the loss of state oversight that would take place if the land is placed in federal trust. The California Coastal Act gives residents the opportunity to participate in the coastal development permit process and other public hearings regarding coastal resources. It also guarantees public access to the state’s beaches.

Federal trust lands carry no such assurance, and several letters to the Coastal Commission argued that the protections offered under the National

Environmental Protection Policy Act (NEPA) pale in comparison to those guaranteed by the Coastal Act. One commenter, for example, referred to the Trump administration’s plans to gut the protections in the federal Clean Water Act.

Trinidad City Manager Dan Berman also submitted a letter enumerating the city’s concerns, which include public access, the rightful land ownership, and the potential loss of tax revenue (including $4,000 in property taxes annually, sales tax from the Seascape Restaurant and bait shop, and transient occupancy tax from the rental home).

The Rancheria’s properties, including the pier, do not extend beyond the “normal high-water mark.” | Map adapted from Coastal Commission graphics.

Coastal Commission staff notes that placing land into federal trust status is a decision for the BIA. The Commission’s role in this case is limited to deciding whether or not the project is consistent with the Coastal Act. And after negotiating some concessions and promises out of the Rancheria, staff has decided that it is. They’re recommending that the Commission concur with the BIA’s consistency determination and approve the project.

Staff does address many of the public’s most pressing concerns. Regarding public access, the staff report says that the Rancheria has agreed to adopt a tribal ordinance promising to coordinate with Coastal Commission staff regarding any future development proposals or changes in public access. (The Rancheria, for its part, says it has no plans for such development.) The Rancheria has also vowed to give the City of Trinidad and other “known interested parties” an opportunity for local input, should such an occasion arise, and it agreed to provide Commission staff with design details for the stormwater improvements and the visitor center, once those plans are prepared.

In a March 1 letter to the commission, Rancheria CEO Jacque Hostler-Carmesin said, “These actions demonstrate that the Rancheria is committed to open public access and has been since negotiations to purchase the properties began. Trinidad Rancheria has owned the harbor properties since 2000, and has never wavered in its commitment to public access in the nearly 20 years since [Emphasis in original].”

At the very least, the pier must remain open to the public. As commission staff notes, the Trinidad pier is listed in the National Tribal Transportation Facility Inventory, which means that it must be open and available for public use.

Hostler-Carmesin’s letter also said, “All Rancheria projects, past, present and future will consider impacts to the harbor environment first and foremost. Allegations that the Rancheria’s actions will harm the environment are extremely false.”

However, neither the staff report nor Hostler-Carmesin’s letter spell out exactly what “coordination with Coastal Commission staff” entails. The Outpost reached out to the Rancheria for comment but did not hear back before this story was posted.

The Yurok Tribe is skeptical of the arrangement. James argued in his recent letter that “an ordinance that could be changed at the whim of the Rancheria is toothless and illusory.” As an alternative solution, the tribe suggested that the Rancheria enter a binding agreement with the BIA and the Coastal Commission, abdicating its tribal sovereign immunity.

Regarding the Rancheria’s rights to the harbor properties, Hostler-Carmesin notes that members “are people of historic Yurok origin,” and she says, “one tribe’s claim of jurisdiction over the entirety of Yurok ancestral territory is completely inappropriate.”

She also says fears about damage to the Tsurai Village and burial grounds are unfounded, as are concerns about environmental damage.

The Coastal Commission staff report notably doesn’t address concerns about Sundberg’s conflict of interest. Sundberg did not respond to a request for comment, though he told the Times-Standard, in a story published Monday, that he does intend to recuse himself from the deliberations.

The hearing is taking place in Los Angeles tomorrow, with the Rancheria’s application about halfway down the day’s agenda. The meeting can be streamed online at cal-span.org.

# # #

DOCUMENTS:

CLICK TO MANAGE