Last week the temperature in Antarctica hit an all-time high of 65 degrees Fahrenheit on Feb. 6, only to beat that record a few days later on Feb. 9, when it hit a high of 69.3 degrees. During this small period of time, a massive iceberg spanning about 116 square miles broke off of the Pine Island Glacier.

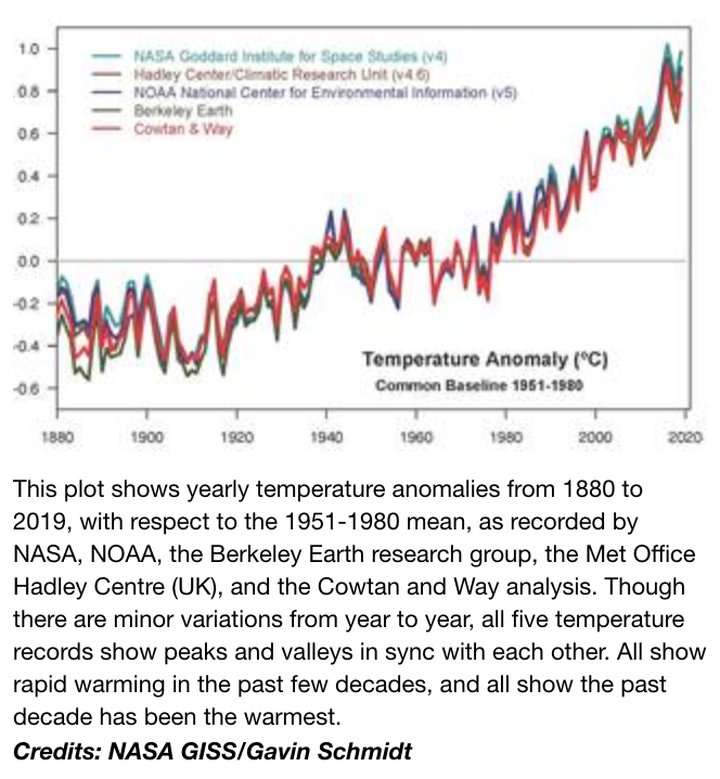

The effects of climate change are starting to be seen as the world heats up to all-time highs. The global temperature for January was the warmest ever recorded. This is just after a joint announcement from NASA and NOAA that the 2010s was the hottest decade on record and that each decade since the 1960s has been warmer than the one preceding it.

“We crossed over into more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit warming territory in 2015, and we are unlikely to go back,” said Gavin Schmidt, the director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, in a statement for NASA on Jan. 15. “This shows that what’s happening is persistent, not a fluke due to some weather phenomenon: we know that the long-term trends are being driven by the increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

Courtesy of NASA

The statement goes on to point out that rising temperatures are contributing to exactly what happened in Antarctica: “mass loss” of glaciers during “extreme events, such as heat waves, wildfires [and] intense precipitation.”

The warming temperatures will contribute to a rising sea level. Here in the Humboldt area, Aldaron Laird has been studying the effects of sea level rise on the Humboldt Bay for the past 10 years. He says that Humboldt Bay is experiencing the fastest rate of sea level rise on the West Coast because the bay sits on a tectonic plate that is being pulled down as the sea level rises. Laird told the Outpost that over the past 100 years or so the waters around the bay have risen around 12 to 18 inches.

About 75 percent of the shoreline around the bay is artificially made, with a majority of it being earthen dikes from the late 1800s. Laird said there are 41 miles of dikes and that they are nearing a critical moment.

Courtesy of Aldaron Laird

“The biggest thing we discovered is that the tipping point for us on the bay is when the water rises two to three feet, which we can experience by 2050,” Laird said. “With just a foot of sea level rise, king tides will start over topping most of the dikes around the bay.”

These dikes protect around 7,500 acres of former salt marshes. Currently resting on those former marshes are homes, Highway 101 and utility infrastructure such as water lines, gas lines and fiber optic cables. The dikes have already been breached at times during king tide events.

In 2005, a storm rolled in with the king tide on New Year’s Eve bringing with it massive flooding. Laird said this event was a 9.6 feet high water event, with the average king tide high water mark being about 8.8 feet.

According to a 2013 study done by Laird, the water levels overtopped dikes around the bay in several locations. The Federal Emergency Management Agency ended up giving $11 million to Reclamation District #768, a small public agency on the north end of Arcata Bay, to rebuild the five miles of dikes that it manages.

So with just a foot of sea level rise, king tides will overtop the outdated barriers on a regular basis. That rise in the sea is expected to come within the next 20 to 30 years.

According to a 2019 County report, the communities of King Salmon, Fields Landing and Fairhaven/Finntown have about 20 years before their landscapes and residential communities are dramatically impacted from rising sea levels.

###

From the intersection of Sole Street and Buhne Drive in King Salmon, it’s about a 100-foot walk to the west to the top of a small dune. The dune rises only about 10 feet and gives you a 360-degree panorama view of the beauty of Humboldt County. The sandy dunes, a few small jetties and rocked and sloped banks are the only major protections for the small town from a rising sea.

The November 2019 report from the Humboldt County Planning Commission says that by 2040, the waters in Humboldt Bay should expect to rise about 1.6 feet, and with it, “king tides will tidally inundate the entire community of King Salmon.”

Back in the 1940s, canals were dug out and sold as access for fishing boats, making King Salmon the community it is today. The entire community sits on 176 acres, but only about 36 acres are developed. There are wetlands, residential communities, businesses and power-generating facilities that sit on the land lined with artificial shorelines.

The sand dunes to the west of town are artificially made. Back in the 1970s, the sand pit eroded so much that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ended up making two jetties to dissipate the incoming waters and created the current dune system in order to protect the town.

Shoreline erosion has already been an issue at Buhne Hill in King Salmon, which has seen about 1,480 feet of its face erode into the sea between the years of 1890 and 1950. This is mostly due to “wave-induced erosion” from the manipulation of the mouth of the bay. Back in 1890, the Humboldt Bay entrance jetties were constructed, and they ended up funneling “high energy waves” at Buhne Hill. Rising sea levels will exacerbate the problem.

Courtesy of Humboldt County

PG&E has an electrical power generating station as well as spent nuclear rod storage facilities atop Buhne Hill. The spent nuclear rod storage facilities are a little over 100 feet away from the sea and are stored in dry storage casks that use helium gas as a cooling method instead of water. With current sea level rise projections, the rock revetment and seawall currently protecting Buhne Hill from erosion may be overtopped during king tides “as soon as 2076 under the extreme scenario, or by 2093 under the high-risk projection,” the County report reads.

PG&E’s current long term plan is to store the nuclear rods onsite until a national repository is built. However, there aren’t any plans to build one.

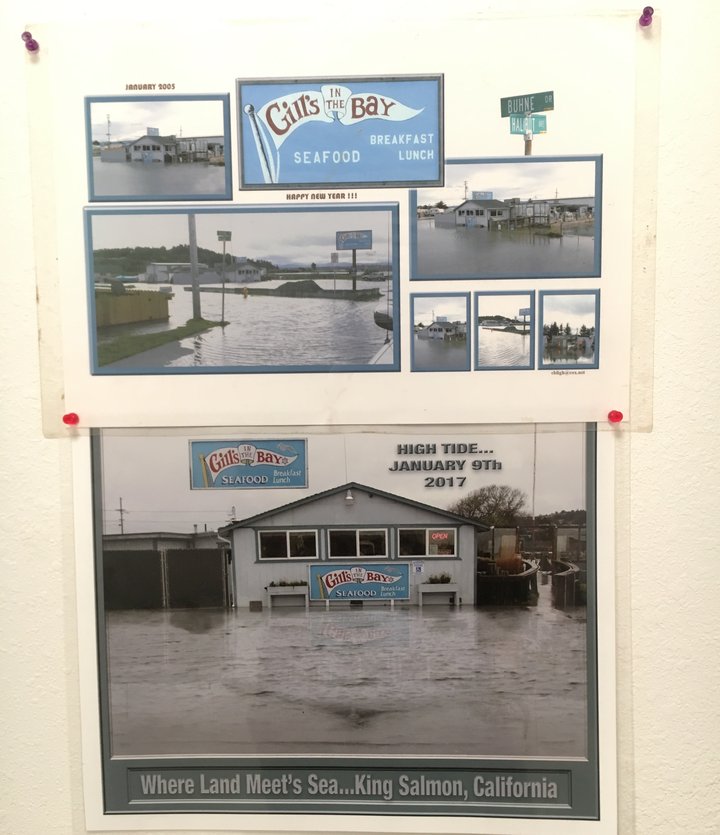

King Salmon Avenue is the only road in and out of the community, and is also in danger of being topped during king tides. The County report estimates that with 1.6 feet of sea level rise, king tides will submerge about 950 feet of the road. Flooding due to tidal inundation in King Salmon has already happened a few times in recent years. Back in January of 2017, the high tides flooded the parking lot of Gill’s by the Bay.

Historic flooding at Gill’s in the Bay. Photo by Freddy Brewster

Other effects of sea level rise include flooding due to rising groundwater and saltwater intrusion. Laird said that the rising groundwater is the secret killer to any sort of development in areas susceptible to rising sea levels.

“Rising groundwater is really the reason why building barriers to sea level rise is just a short-term measure,” Laird said. “You could have a nice rocked dike protecting an area from being tidally inundated, but the low-laying areas behind the dike are all going to flood from rising groundwater. You don’t want to over-invest in building fortified dikes along the shorelines when all of the low-lying areas behind it are going to flood.”

###

The communities of Fairhaven and Finntown rest on former sand dunes just to the north of Humboldt Bay. Saltwater intrusion will be one of the main concerns in Fairhaven and Finntown. As the sea level rises, the saltwater will push the freshwater to the surface, which can cause pooling. The pooling of the groundwater is expected to cause a problem with the septic systems in these areas.

“By 2040, saltwater intrusion could affect underground septic tank leach field systems in the area east of Lincoln Avenue in Fairhaven on a daily basis,” the county report states.

Much like King Salmon, these two communities will face chronic tidal inundation during king tides by 2040 and will be “perennially flooded” with an estimated 3.3 feet of sea level rise by 2065. The residential areas are generally unprotected from rising sea levels and only have sandy shorelines breaking the “reflective waves that bounce off the sea wall in front of the railroad grade across from the entrance to the bay,” the County report states.

Fields Landing is already dealing with side effects from rising sea levels. Currently, water rises out of the storm drains in the small town during king tides, causing flooding in the streets.

Courtesy of Humboldt County

An old railroad grade extends out into the bay on the north and south ends of the community, which provides a possible pathway for tidal inundation as soon as 2040 during king tides. With just 1.6 feet of sea level rise, king tides will inundate the residences and businesses in the low-lying areas of Fields Landing and by 2065, “nearly all developed areas of Fields Landing could be chronically inundated” during the monthly high water marks.

###

But the County is working on solutions. Back towards the beginning of 2019, the County began a collaborative project with the Redwood Coastal Energy Authority, and the cities of Arcata, Eureka, Blue Lake, Ferndale, Fortuna, Rio Dell and Trinidad to develop plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The “Climate Action Plan,” as it is called, aims to identify the main causes of GHG emissions, set a reduction target for the community to meet and then formulate an interagency plan for the best ways to reduce them.

“With this [Climate Action Plan], the County will work with residents to develop emissions reduction strategies that enhance our local economy, improve community health and build resilience to climate-related hazards,” a statement reads on the County website.

So far, the CAP partnership has had six meetings so far. Five of the meetings were with members of the public in a handful of committees to workshop ideas on how to best address climate change.

The County also has a plan for how to best retreat from the rising sea. John Ford, the director of the Planning and Building Department, said the County plans to address sea level rise with three phases: recognizing the change, protecting the infrastructure for as long as feasible and then a planned retreat.

“The basic concept is to resist sea level rise and respond to it as long as feasible,” Ford told the Outpost. He went on to say that protecting the areas is only viable if it is economically sustainable. Currently, the County has no cost estimates as of yet, but Ford said protecting the value of the homes is “one of the things we are concerned about.”

He said one of the earliest improvements that the County could invest in is raising King Salmon Avenue. Another option are for homes to be raised with breakaway ground levels where the sea can pass through them without damaging the main living areas. There are currently two such residences that were recently constructed in King Salmon.

The homes with breakaway bottom levels in King Salmon. Photo by Freddy Brewster

But these aren’t really long-term solutions; they are just sort of delaying the inevitable. Laird said that the communities will be able to exist for only as long as the utilities will be able to serve those areas, and he doubts there is enough money to raise all of the properties in the future flood zones.

“Essentially the communities of King Salmon and Fields Landing and Fairhaven are not really going to be able to exist with two and three feet of sea level rise,” Laird said. “They will just be underwater, and we will probably lose those communities. When the utilities can’t service those properties, they are not going to be habitable.”

Laird said he would like to see the County create a “sea level rise hazard zone” around the bay. He said the zone would mark the extent of the projected sea level rise of one meter and would help to prevent any new developments from being built within the zone. It would also prevent any sort of redevelopment of existing structures already in the zone.

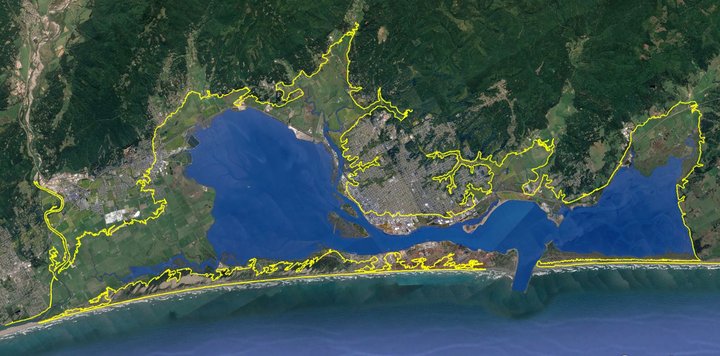

Laird said another fix is to better educate the public of the possible future effects. He said he created a map of future sea level rise projections that extend out to 2120. Everything under a certain level is just a “temporary development that is going to be inundated,” Laird said.

“Instead of squabbling about one foot of sea level rise or two or three feet, let’s just look at where it is going to be a century from now,” he continued. “We shouldn’t be building permanent infrastructure that needs to be protected from rising sea levels.”

Laird’s estimation of 20 feet of sea level rise by 2120 demarcated by the yellow lines

CLICK TO MANAGE