Photo courtesy Humboldt County Growers Alliance, by Anda Ambrosini.

###

The County of Humboldt is preparing to hand out more than $1.2 million worth of services to local residents who’ve been impacted by the war on drugs — specifically, cannabis prohibition. Anyone who meets the eligibility requirements can apply for up to $10,000 in reimbursement for a range of services, including permitting and license fees, business development assistance, even loans and grants to set up solar electrical systems or build water storage capacity.

This infusion of capital into the region’s cannabis economy comes via the county’s Project Trellis Local Equity Program (Version 1.0), which got its funding from the state’s Bureau of Cannabis Control, plus local Measure S tax revenues.

It’s a not-insignificant windfall for the burgeoning legal weed industry, and it looks likely to be just the first in annually recurring waves of state and local money ushered in by Senate Bill 1294, the California Cannabis Equity Act of 2018. And it has sparked conversations within the industry about who is most deserving of the help and how the money can best be put to use.

In recent years the concept of equity has been trending, you might say, in the realms of politics, education, health care and more. (See recent stories on COVID-19 vaccine distribution, for example). Equity has become something of a buzzword, albeit a meaningful one that sparks conversations about such issues as diversity, representation and systemic oppression.

But what does “equity” mean in the context of cannabis? Does it differ depending on which community you’re in? Or the upbringing you had? Or your race and gender? Locals in the cannabis industry, county government and beyond have been grappling with such questions as they attempt to help level a playing field that’s been uneven for generations.

Under SB 1294, the specific criteria for issuing awards are developed by local jurisdictions. (We’ll get into how Humboldt County developed its criteria below.) But broadly speaking, the legislation is intended to address what its author, SoCal State Senator Steven Bradford, calls the “devastating impact[s]” and “long-term consequences” of cannabis prohibition.

That includes racial disparities in marijuana arrests and convictions. It also includes the trauma endured by Southern Humboldt families whose properties were raided by paramilitary forces during CAMP operations.

But should those two examples be given equal weight? How do you compare one person’s injustice to another’s in the quest for equity?

“It’s really hard because they’re not apples and apples,” Drew Barber, owner of East Mill Creek Farms, said in a recent phone interview. “Generally speaking, Humboldt County’s equity issues — and this is not without counterpoints — but it’s mostly Anglos who have, for one reason or another, chosen to participate either in this community or in the cannabis economy.”

“There’s no question, Humboldt County was adversely impacted by the war on drugs. … Having your home raided by the National Guard, kids taken away from their family — that’s a pretty big deal.”

—Drew Barber

Which isn’t to say that people here didn’t suffer from cannabis prohibition. “There’s no question, Humboldt County was adversely impacted by the war on drugs,” Barber said. “Nobody [living in SoHum] was unaffected by the low-flying helicopters over the years. Having your home raided by the National Guard, kids taken away from their family — that’s a pretty big deal.”

Barber believes reparations in the form of equity programs are appropriate for people who endured such experiences. “But when we look at the African American plight in cannabis [prohibition], it’s much longer-term and it’s much more targeted,” he said. “They don’t get to make a choice about their race.”

Black people are 3.6 times more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana possession, despite similar usage rates, according to a 2020 data analysis from the ACLU.

“Native Americans also,” Barber added. “How can we stand here and talk about egregious things that happened to us over the last 30 years when they’ve suffered much more heinous and systematic trauma? … The argument is easily made: ‘Hey, you wouldn’t have this land to grow weed on if you didn’t steal it.’ Which is 100 percent true.”

###

Should cannabis equity programs attempt to address such historical injustices? Or should the focus be more narrow?

Andelain Roy was born and raised on a cannabis farm, and one of her earliest memories is the deafening sound of CAMP helicopters descending on her family’s SoHum property. As troops with machine guns rappelled out of the thundering aircraft, Roy remembers an adult swooping her up and running for cover.

“This person was holding me, covering my mouth, and I could feel his heart pounding,” Roy said. “Here we are, just a family. I mean, yeah, we had several cannabis plants in the garden, but it was mostly orchards.” The experience was formative, she said. “It was terrifying.”

As kids, Roy and her closest friends adopted a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy regarding their parents’ livelihoods, and this culture of secrecy left gaps in their understanding of the industry.

“I feel legacy cultivators weren’t really able to develop their business skills,” Roy said. The highly regulated legal market involves countless tasks that her parents never had to deal with, like getting licenses and permits from myriad government agencies and navigating metrc, the state’s online track-and-trace program. “There’s a big need for education on even how to start your business and run it compliantly,” Roy said.

But like Barber, Roy is aware that others have faced more significant barriers to success in the industry.

“Unfortunately, I feel like the Black and brown community, they were affected a lot more than someone like me,” she said. “I’m white, so it’s much easier for me to function in the world. I have a lot of conversations with my community, which is mostly Caucasian: ‘Is this fair? Is this right? Should I even apply [for equity funding] as somebody with my privilege?’”

As a woman, though, she has faced discrimination in the industry — men who’ve dismissed her as a “hippie with flower crowns” rather than the competent professional she is. (Roy owns DewPoint Farms, a licensed cultivation operation near Honeydew.) Her gender and her upbringing qualify Roy to apply for Humboldt County’s first round of equity funding.

“Do I deserve it?” she asked. “Yes, I think so.”

But does she deserve it more than, say, Alonzo Bradford? In a recent phone interview, Bradford told the Outpost he’s pretty sure he’s the only African American dispensary owner in Humboldt County. (He co-owns Dr. Greenthumbs in Myrtletown with Cypress Hill emcee B-Real.)

A second generation “legacy” farmer, Bradford (no relation to the Senator who authored SB 1294) came to Humboldt at the dawn of legalization because a friend of his weed-growing father had property for sale. Bradford said discrimination threw up numerous hurdles in his attempts to get established here. Some of them were due to the color of his skin.

“I would have to explain to people the experience I went through as 24-year-old African American from Los Angeles,” he said. “Like, when I told [prospective landlords] that I planned to open a dispensary legally, people said, ‘I don’t believe you’ or, ‘I’d rather not risk it,’” Bradford recalled.

He also faced discrimination for being an outsider — someone without connections in local government or a family name that goes back multiple generations in Humboldt.

“There’s not enough talk about the gatekeepers. … When it comes to being African American, you tell people your experience and they dismiss it. You’re constantly having to prove yourself.”

—Alonzo Bradford

“There’s not enough talk about the gatekeepers,” Bradford said. “When it comes to being African American, you tell people your experience and they dismiss it. You’re constantly having to prove yourself — to your landlord, to the county [government], to locals who feel like you can’t grow because you don’t have land that goes back generations.”

That’s another kind of privilege that should be factored into equity equations, Bradford said: land ownership. While plenty of Humboldt County residents got arrested and even jailed for growing cannabis, many of them retained ownership of their land, he noted. After getting busted they could just borrow some seeds from a neighbor and start up again. Meanwhile, Bradford said, Black people in the Bay Area and Southern California were serving hard time for selling the product grown in our hills.

“When we think of equity up here [in Humboldt], it shouldn’t be a Black or white thing,” Bradford said. “It should be [about] what’s fair for the community, what makes it right. It should give a leg up to those who didn’t have those opportunities.”

###

So how does the cannabis equity funding work here in Humboldt?

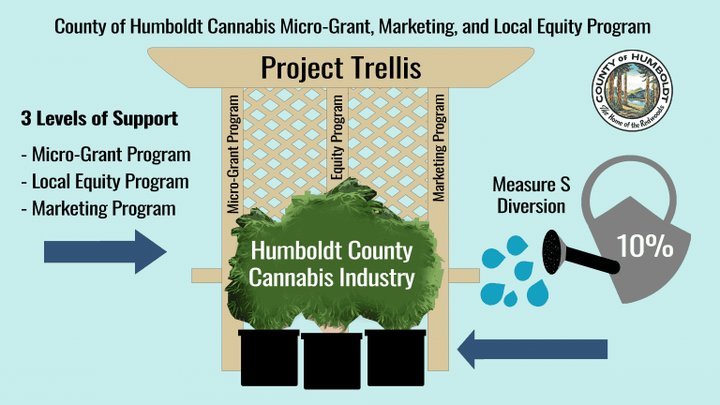

Version 1.0 of the county’s Local Equity Program is being administered by the Economic Development Department. The Outpost recently spoke with Scott Adair, that department’s director, and Peggy Murphy, an economic development specialist who’s overseeing Project Trellis, the county’s three-tiered cannabis support initiative. (The tiers include the equity program, a micro-grant program and a marketing program.)

Adair explained that the county’s eligibility criteria and list of services were developed in collaboration with the Humboldt Institute for Interdisciplinary Marijuana Research (HiiMR) and the California Center for Rural Policy (CCRP) at Humboldt State University. In 2019, those two research institutions released a joint study called the Humboldt County Equity Assessment, which includes a list of findings and recommendations based on “a data-informed look” at how cannabis prohibition impacted the community.

That report informed the eligibility requirements in the county’s cannabis local equity program manual. Some of the criteria are simple. For example, any woman, person of color or LGBTQ individual working in the industry (or even those who used to work in the industry) qualify. As do people in the industry who’ve been arrested and/or convicted of a non-violent weed offense, or who were subject to asset forfeiture due to a “cannabis-related event.”

Locals who’ve experienced “sexual assault, exploitation, domestic violence, and/or human trafficking” while working in the industry also qualify, as does anyone who became homeless as a result of marijuana enforcement. Other criteria are based on local poverty rates, time living in the county and — one of Bradford’s suggestions — operating a small-scale garden on property you don’t own.

Adair said the county’s program is not designed to address social equity writ large. “It’s more about the inequity that exists between some individuals who may face different levels of barriers to access, or who have greater leverage or privilege over others,” he said. “The equity program offers support for those who can’t overcome those barriers on their own.”

That support could come in the form of fee waivers or deferrals, technical assistance, employment skill training or a variety of other services. As noted above, eligible applicants can apply for up to $10,000 per service.

Humboldt County was proactive in developing its Local Equity Program. “I believe ours was the first completed [in the state],” Adair said, adding that the HiiMR and CCRP have gone on to help neighboring counties and other jurisdictions develop their own equity assessments.

Getting on the ball so quickly helped the county secure nearly $3.7 million in funding from the state, but it also locked the county into a contractual agreement with the Bureau of Cannabis Control. That means the eligibility criteria for this round are fairly rigid and largely dictated by the state’s Bureau of Cannabis Control, according to Adair.

But Murphy said the county has applied for another round of funding through the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz), and hopefully that source funding will be available annually.

“Equity programs are evolving at the state and local level,” Murphy said. “We plan to continue to get community engagement and gather more data so we can improve our understanding of those affected populations.”

Some people working in the local cannabis industry have been critical of the county’s equity efforts thus far, and they have suggestions for how the system might be improved.

Timo Espinoza is a second-generation grower who came to Humboldt from San Francisco, where he’s been “equity verified,” meaning he has met the city’s criteria for its own cannabis equity program. The equity issues in the Bay Area are largely about gentrification, Espinoza said, noting that minorities and cannabis businesses alike have been pushed out by tech companies like Twitter.

Grassroots organizing efforts among cannabis advocacy groups in San Francisco had a major impact on the city’s equity program, and Espinoza said there should be similar efforts here in Humboldt.

“Only the community can voice their needs,” he said. “I understand to an extent what the needs are, but let’s be real. My trauma and my needs are different than Humboldt County’s.”

Espinoza, who’s Black Latino, is running a manufacturing and distribution facility in Arcata, with a delivery-retail component, and he said he’s faced discrimination locally.

“I’ve had the police called on me just for being on the property — my property,” he said. “I’ve been pulled over multiple times on the freeway coming up [from San Francisco].”

Yet he doesn’t believe equity, in this context, should be all about race. “I believe it’s not about demographics; it’s about how you’ve been affected by the war on drugs,” he said. “Humboldt County’s a special place. Nobody else had to deal with CAMP raids like you did.”

His idea for the equity program? “I would say let’s set up mental health services for people who do have PTSD from the helicopters,” he said.

Barber said the money would go farther if it could be awarded to businesses, co-ops or industry organizations such as the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, which could help more locals acquire the executive and business skills necessary to succeed in the regulated marketplace.

“My take is if you give someone a $10,000 grant to participate in a business that costs multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars … in community that’s already relatively impoverished, it doesn’t seem like recipe for success,” Barber said. “I wouldn’t recommend that someone get involved [in the industry] largely or in part because they got a $10,000 grant. … It seems like recipe for disaster for them.”

And by the same token, for someone who’s already fully licensed, up and running, $10,000 in services isn’t likely to make or break them, he said.

Barber is a member of an agricultural cooperative of cannabis cultivators called Uplift, and he argued that if co-ops like his were allowed to apply for cannabis equity funding, “you could get so much more bang for your buck that way.”

Alternatively, he argued that Humboldt’s cannabis community should work to improve its connections with urban counterparts in Oakland and San Francisco.

“Historically, over the last 35 to 40 years, we’ve kind of gotten into this trouble together,” Barber said. “Like, Humboldt grew the weed and our urban counterparts would sell it. The Anglo people in Humboldt got CAMP while the African American people in Oakland were constantly under threat of arrest … . We need to use this equity [initiative] not as competition, but we really need to work together to remedy some of those inequities.”

Working collaboratively could produce benefits throughout the cultivation and distribution chain, he said. “We got in it together, so let’s get out of it together.”

Natalynne DeLapp, executive director of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, said the county simply needs to hear more from the local community. In an emailed statement, she said the HCGA encourages the county’s economic development department to “reach out to the community” and “commence countywide listening sessions to hear directly from those impacted by the war on drugs.”

###

Adair said that while the criteria for this first round of funding is fairly set in stone, and based mostly on requirements from the state, the county is by no means finished developing its cannabis equity program.

“There was admittedly a bit of rush” developing version 1.0 of this program, he said, so his department relied heavily on the county’s 2019 Cannabis Equity Assessment. “We were up against a tight timeframe. … But because we expect this [funding] to be annual, this can be a living program that we can continue to monitor and adjust annually moving forward.” Adair and his staff plan to hold town hall meetings, as they did during the development of Project Trellis’s micro-grant program.

“The industry is going to keep changing and equity will continue changing, so we don’t want an outdated program.”

—Economic Development Director Scott Adair

“The industry is going to keep changing and equity will continue changing, so we don’t want an outdated program,” Adair said. “We will continue to have discussions with the community. … Our challenge has been trying to get these programs developed quickly, which left us with a quandary: When do we stop trying to perfect the program and when to do we get the money out into the community?”

Ultimately, Adair said, the program will benefit the community and the industry, even if the conversations it stimulates are sometimes awkward.

“I think that this is a good problem to have,” he said. “It’s a great discussion, trying to figure out who will get [the benefits] and how to spend this money. … We’ll continue to refine it, and we will need stakeholders to give that feedback so we can, one, give that feedback to the state and, two, incorporate that into improvements in the program moving forward.”

Murphy said the county hopes to hear back from the state regarding the next round of funding by May. And in April or thereabouts, the Economic Development Department plans to release a request for proposals for a cannabis marketing initiative — the third upright in the county’s Project Trellis industry support program.

The money waters the weed, which grows tall and strong on the “trellis.” Graphic: County of Humboldt.

CLICK TO MANAGE