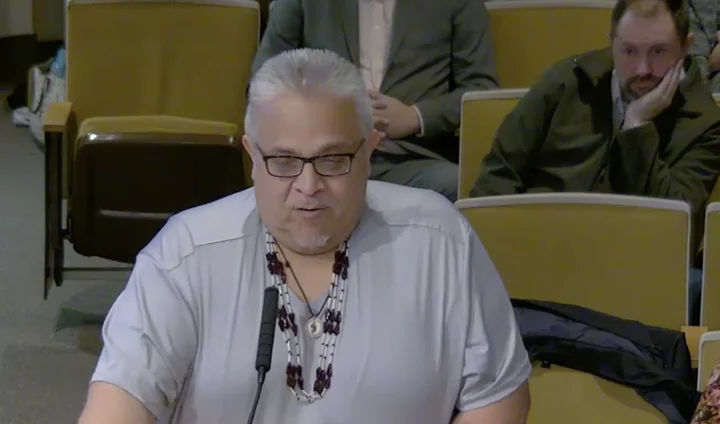

Wiyot Tribal Chair Ted Hernandez addresses the Board of Supervisors as property owner Jeff Meyer looks on. | Screenshot.

# # #

# # #

At Tuesday’s meeting of the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors, Wiyot Tribal leaders stood firm in defense of their right to protect tribal cultural resources, even if it spells doom for a planned cannabis production and distribution compound at the former Sierra Pacific lumber mill site near Mad River Slough.

For close to two years now, a group of out-of-town investors — organized as Humboldt Bay Company, LLC — has been working to develop the vacant 70-acre industrial parcel into a commercial cannabis operation featuring more than seven acres of indoor cultivation space alongside facilities for distribution, manufacturing and more.

However, the project area, on the banks of Humboldt Bay, sits atop a Wiyot village site that was likely destroyed during construction of the mill, according to a county staff report. The three tribes with ancestral territory covering the area — the Wiyot Tribe, the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria and the Blue Lake Rancheria — initially just asked for a tribal monitor to be on hand during construction, with specific protocols to follow should something of cultural significance be discovered.

During the project’s environmental review, however, county staffers in the Planning and Building Department embarked on more formal consultation with the local tribes, as required by the California Environmental Quality Act and Assembly Bill 52. In response to this outreach, the Bear River Band sent the county a letter expressing full support for the project. The Blue Lake Rancheria took no position. But the Wiyot Tribe took a stand.

In August, the Wiyot Tribal Council officially declared the site a Tribal Cultural Resource. Because the county’s Commercial Cannabis Land Use Ordinance (CCLUO) requires a 600-foot setback from such resources, this represented a major roadblock for the development — perhaps even a deal-breaker.

The project backers didn’t give up, though. At today’s hearing they asked the Board of Supervisors to let the project go forward despite the Wiyot Tribe’s objections.

Planning and Building Director John Ford explained the situation to the board, noting that the county’s commercial cannabis ordinance doesn’t have any provision to resolve such a dispute — that is, when two tribes don’t object to a project but a third one does.

Ford’s own reading of the ordinance was clear, though: He told the board that the “black and white” of it says that if a tribe identifies a cultural resource — and “it doesn’t matter if it’s one of three [tribes]” — then the resource “needs to be protected and respected.”

“So, can anything else be built on the site,” First District Supervisor Rex Bohn asked. “Like, could they go back to a sawmill that was there for 74 years?”

Ford explained that while there’s leeway in state environmental law to override such environmental impacts, the county’s cannabis ordinance offers no such wiggle room.

“So it’s not an absolute prohibition on anything other than cannabis,” Ford said.

Wiyot Tribe Chair and Cultural Director Ted Hernandez addressed the board, saying the tribe doesn’t really know what’s buried under the property’s thick layer of cement. In the early 1900s, “everything was bulldozed into the slough,” he said, though he added that there may still be gravesites out there.

He also suggested that the Wiyot Tribe’s position can’t be superseded by those of other area tribes.

“Let me be frank,” he said. “This is Wiyot territory. This is Wiyot ancestral territory; it states in our constitution where our tribal boundaries lie. And I know Bear River is our cousin tribe … and we do recognize that they have Wiyot descendants in their tribe. But once you leave the Wiyot Tribe, you don’t speak for the Wiyot Tribe.”

He said the village site was also a ceremonial site because anytime a resident was sick or died, fellow tribe members would hold ceremonies in his or her house.

“And this is why we have to protect it,” Hernandez said. “We weren’t able to protect this site in the early 1900s when it was destroyed, but now we’re able to.”

Bohn took issue with the timing of this stance. “Working forward, there’s gotta be a better way we can do this,” he said, noting that the Wiyot Tribe had “basically agreed” with other tribes back in October of 2021, when all three tribes asked merely for a tribal monitor to be onsite during construction.

Bohn said this earlier communication — which, according to Ford, was never meant to be released publicly or interpreted as formal approval — put the applicants at ease, convincing them that it was safe to invest more money.

Hernandez responded that the tribe was merely following the terms of the ordinance created by the county. He later added that tribal historic preservation officers “don’t make decisions for our tribe.” That authority lies solely with the tribal council.

Bohn again searched for wiggle room, asking Hernandez if the tribe would be willing to reduce the 600-foot setback.

Hernandez said that if the applicants really want to find out what’s on the property, they’d need to tear up the concrete and conduct a full archeological survey.

John D. McGinnis, at-large tribal council member with the Bear River Band, said his tribe doesn’t consider the site a tribal cultural resource because it’s inaccessible, buried beneath “a couple million cubic feet” of concrete. He also challenged Hernandez a bit, saying “Wiyot land” shouldn’t be interpreted to mean it’s only the Wiyot Tribe’s concern.

“When we talk about Wiyot land, it is all three tribes,” he said, adding that he sees the cannabis project as “a massive opportunity for the county.”

Robert Marshall, the CEO of Humboldt Bay Company’s parent corporation, Victorum, stood at the lectern next with a couple of his fellow executives and told the board that while they didn’t have any formal agreement with Hernandez or the Wiyot Tribe, they were nonetheless “very confused” by this latest development.

They’d paid for an archeological study that found no cultural or archeological resources of any significance, “so in our mind, we were moving forward,” Marshall said. They met with Wiyot tribal council members “hat in hand” and asked what they needed to do, he said.

“This is a passion project for us,” he continued. “This is not just about cannabis. This is about coming in and building a world class, long-term model of the industry.”

Property owner Jeff Meyer also addressed the board, expressing deep frustration with the situation. He referenced the county’s earlier communication with tribes and the archeological study that found no resources.

“They found nothing significant on that property and it was signed off on by all three tribes,” Meyer said. “Done deal. Why are we here? … [The investors] spent up to half a million dollars on this process that the county allowed them to proceed with, and then all of a sudden, for some reason, they asked the tribe again for approval. It was already approved! We have it written. This is a done deal.”

Meyer said he worries about the precedent this sets for future developments.

“The way I understand now, every piece of property I buy could have this tribal influence on it and it’s a shut-down project,” he said.

Meyer acknowledged that there were once two Wiyot villages on the property but said this project wouldn’t negatively impact any artifacts.

“One of [the village sites] is on the north end of 30 acres that can never be used [and would be] turned into a wonderful park. If they find artifacts on it? Wonderful. The other is under three feet of asphalt that’s been rolled over for the last 60 years, and they’re not going to disturb that land,” he said.

Ford reiterated that the three tribes’ earlier request for a survey and site monitor didn’t represent “approval” of the project.

Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone said, “I think these kinds of issues will continue to come up over time because of unclear boundaries between rancherias and tribes and the assertion about who has ancestral rights. … . I don’t know what the solution is there, but I doubt this will be the last time this comes up.”

During the public comment period, Wiyot Tribe member and tribal council secretary Marnie Atkins said the division of Wiyot people’s family and land into separate tribes with distinct territories “is a direct result of colonization and genocide inflicted upon Soulatluk people,” a reference to Wiyot language.

The issue before the board is also a product of that history, she said.

“Our ancestral homelands range from Plhut Gasamuli’m (Little River) in the north to Tsakiyuwit (Bear River Ridge) in the south, from Shou’r (Pacific Ocean) in the west to the first set of Qus (hills/mountains) to the east. Waterways in the ancestral lands of Wiyot people include Baduwa’t (Mad River), Hikshari‘ (Elk River), Wiya’t (Eel River), Girrughurralilh (Van Duzen River) and Wigi (Humboldt Bay).”

As stewards of those ancestral lands, she said, “protecting our traditional cultural resources is one of our most sacred tasks.” Atkins asked the board to consider how’d they’d feel about having a concrete cap put atop Sunset Memorial Cemetery or Ocean View Cemetery.

“I’d like to argue that just because you cannot see a burial [site] or recognize a sacred site does not mean that it does not exist,” Atkins said, and she urged the county to meet with a tribal government and develop a permitting process that considers the federal and state laws protecting such tribal cultural resources.

After the public comment period, Second District Supervisor Michelle Bushnell asked Hernandez if there was any room for negotiations with the tribal council. Bohn asked the same thing, in different words, saying, “It’s not just this project I’m concerned about.”

Hernandez again said the tribe merely followed the methodology of the county’s cannabis ordinance, and he suggested that county staff re-engage with tribes to create a new one or modify the existing one.

“For me it’s pretty simple,” Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson said. “I think that the staff’s interpretation of the ordinance is correct.” In other words, he agreed that there was nothing the board could do but accept the Wiyot Tribe’s decision.

Wilson added that the board could theoretically direct planning staff to reevaluate the existing cannabis ordinance and modify its tribal consultation process, but he worried about further burdening staff given the extensive backlog of work on their plates.

The board debated what to do next — form a new cannabis ad hoc committee? Direct staff to work on new cannabis ordinance amendments? Or simply accept staff’s recommendation and leave it at that?

Bushnell wound up making a motion to do the latter, formally accepting the Wiyot Tribe’s determination that the site is a tribal cultural resource. By all appearances, this effectively kills the planned cannabis facility at the old mill site. The board passed the motion via a 4-1 vote, with Bohn dissenting.

In a separate motion, passed unanimously, the board directed staff to come back at a future meeting with a “comprehensive set of issues” to be addressed under the CCLUO, along with an item to discuss the possible formation of a cannabis ad hoc committee.

CLICK TO MANAGE