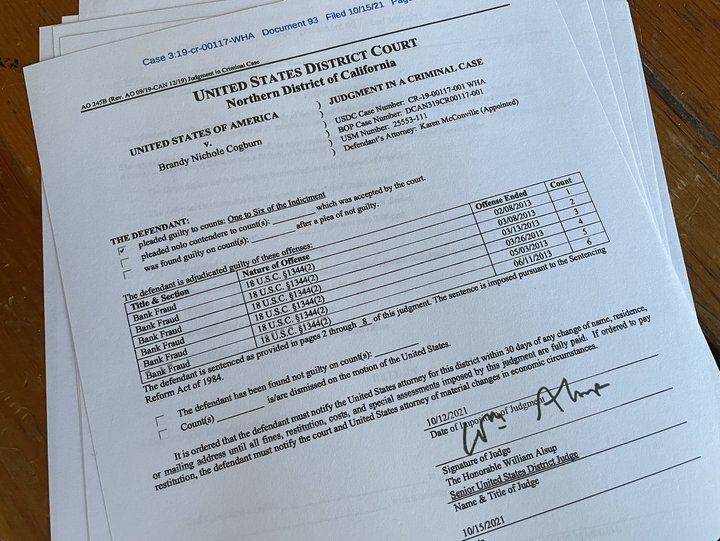

A copy of the judgment.

###

A Manila woman is headed to federal prison next week after pleading guilty to bank fraud committed while working as the fiscal director of the Wiyot Tribe.

Brandy Cogburn, 44, has been sentenced to a 21-month prison term, plus three years of supervised release, and ordered to repay the tribe $95,001. According to court documents, she executed a multi-pronged embezzlement scheme over a period of about five months in 2013 by overpaying herself, cashing out unearned vacation hours and using tribe-issued checks and a debit card for personal gain. She has been ordered to surrender herself on Tuesday, Feb. 1, to begin serving her sentence.

Hired by the Wiyot Tribe in 2012, Cogburn’s employment there ended in 2015, shortly after the Wiyot Tribal Council launched an internal investigation into the tribe’s own fiscal department.

“The primary issue was the failure to complete audits,” Wiyot Tribal Administrator Michelle Vassel told the Outpost in an email. “During that time, it was hard to determine what exactly was going on. Brandy was good at shifting blame and creating an adversary environment which made it hard to see the whole picture.”

She was placed on leave and quit via text message not long afterward, according to court documents. After its internal investigation, the tribe wound up referring the matter to the U.S. Office of Inspector General, whose own investigation would take four years to complete, according Vassel.

In the meantime, Cogburn was hired as the financial controller for the North Coast Co-op. During her tenure there, the Co-op was in a state of upheaval, mired in internal squabbles and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy due to a variety of internal and external factors. A few employees tried to blow the whistle on “financial malfeasance” they’d observed, including irregular accounting methods and a lack of transparency, but management stood behind Cogburn — for a while, anyway.

The North Coast Co-op wound up firing Cogburn in late 2018 for “incompetence” and later sued her in small claims court. The case accused her of embezzlement and theft, saying she racked up $1,366 in unauthorized personal charges on the company’s credit card, wrote the Co-op a check that bounced and absconded with a company-issued laptop.

The Outpost published a couple of stories in late 2018 about the Co-op’s internal strife and financial troubles. The general manager and board president at the time said they had investigated the allegations of embezzlement, with help from the Co-op’s auditor and legal counsel, and found no evidence to support them.

However, the case records on file at the county courthouse include copies of letters that Co-op managers and a hired attorney sent to Cogburn in the summer and fall of 2018. The letters demanded the return of the company laptop and threatened legal action if she failed to reimburse the Co-op for her fraudulent credit card charges.

Calls and emails to the North Coast Co-op’s current board and management this week have not been returned.

As for Cogburn’s Wiyot-related shenanigans, the chickens came home to roost, so to speak, on March 12, 2019, when a grand jury from the U.S. District Court’s northern California division indicted Cogburn on six counts of bank fraud.

According to the indictment, Cogburn wrote a series of unauthorized checks on behalf of the tribe and deposited them into a Redwood Capital Bank account that she controlled. She also used a debit card to withdraw funds from a tribe-owned checking account, falsely telling merchants that she had tribal authorization, and she manipulated the payroll system to give herself an unauthorized raise, issue herself double paychecks, rack up unearned vacation hours and take excessive holiday bonuses.

In interviews with federal authorities, Cogburn’s former colleagues describe her as a rodeo enthusiast who was often aggressive and confrontational. They say she had trouble completing basic bookkeeping tasks and often failed or refused to turn over documents they requested. When she did turn them over they were often riddled with errors or filled with suspicious, seemingly random figures. She’d spent a decade working at Mid-City Motor World before coming to the tribe, and in 2012, shortly after she was hired, she earned a degree in accounting and finance from Humboldt State University.

Cogburn used tribal accounts to purchase “a lot of horse equipment,” “cowboy stuff” and “farm stuff” such as livestock feed, according to employees interviewed by federal investigators. The tribe’s then-environmental director, Stephen Kullman, found such purchases suspicious since the tribe didn’t own any horses or livestock.

Cogburn’s case was assigned to Senior District Court Judge William Alsup and began wending its way through the judicial process. Cogburn initially pleaded not guilty but after a series of preliminary hearings and status conferences throughout 2019, a change of plea hearing was scheduled for early 2020. After a series of delays — some related to the COVID-19 pandemic — Cogburn, through her attorney, submitted an application in October 2020 to change her plea to guilty.

Prior to sentencing, Cogburn’s appointed attorney, San Rafael-based Karen McConville, submitted to the court a memorandum quibbling with some of the dollar figures involved in her client’s fraud and asking the judge for leniency. The U.S. government, as plaintiff, had recommended a sentence of 21 months in prison, but McConville said Cogburn should instead receive six months of home confinement followed by five years’ probation and 500 hours of community service.

“Needless to say the power and authority given to Ms. Cogburn lead [sic] her to abuse it for herself and for that she is guilty of criminal misconduct,” the attorney wrote, but she argued that her client wasn’t entirely to blame. “She inherited a broken fiscal system in [the] process of being upgraded and [was] abandoned by her predecessors. She didn’t have the experience or the ability to do the job she was hired to do and should have resigned when that became clear to her, but she needed the job, and the Tribe was happy that she acquiesced to requests that they benefited from personally too.”

Cogburn is repentant, McConville told the court.

“She is not inclined to repeat the mistakes of her past, including those at North Coast Co-Op, a position she took on after she left the Tribe,” McConville argued. “Ms. Cogburn is atoning for her past misconduct by giving back to her community through ‘Horses That Settle’ which she also opened in 2018. This program allows for children and adults to be with animals on her property free of charge. She also has a program for suicide prevention.”

In response to this plea for mercy, Assistant U.S. Attorney Kristina Green submitted a memo of her own, arguing that Cogburn deserved no such thing. Not only did she commit premeditated and complex fraud, Green argued, she had also submitted a fabricated letter of support in one of her prior sentencing memos.

Cogburn had given the court an undated letter signed only by “a Tribal member, employee and friend” who claimed to have worked with Cogburn from 2012-2015. Cogburn said the author was reluctant to reveal their identity for fear of retribution.

Questioned about the letter’s authenticity, Cogburn initially said it had been written by Fawn Lopez, an administrative assistant with the tribe. However, Lopez later testified that she wasn’t the author. Under further questioning, Cogburn claimed the letter had actually been written by a man named John Richardson, who, it turned out, lived in Reno and had never been a member or employee of the Wiyot Tribe.

Prosecutors called Cogburn’s claims about the letter “preposterous” and “nonsensical.” Since the letter was clearly fake, they argued, Cogburn should be subjected to a “two-level enhancement” to federal sentencing guidelines.

As for the argument that Cogburn had inherited “a broken financial system” and was not alone in benefiting from her corruption, federal prosecutors weren’t swayed.

“Cogburn’s shirking of responsibility and pointing the finger at others sidesteps a key point, which is that she was the fiscal director,” Green argued [emphasis in the original].

She continued:

As fiscal director, it was her duty to lead by example and ensure the finances were managed appropriately. She not only failed in these responsibilities but used her role to steal and now tries to blame her fraudulent behavior on other circumstances.

The manner in which the defendant executed her fraud, far from demonstrating financial inexperience, reflects her criminal sophistication. She used any and every means available to embezzle. She used the Tribe’s debit card to pay for personal items; she called Citibank to pay off her personal credit card expenses using the Tribe’s account information; she manipulated the payroll system to increase her salary payments without authorization; and she took unauthorized leave cash outs.

Judge Alsup sided with the prosecution, sentencing Cogburn to the full 21-month sentence they’d sought.

Vassel, the Wiyot tribal administrator, said she was told by the U.S. Attorney’s Office that Cogburn was given a severe sentence “due to the sophisticated nature of the criminal activity.”

Vassel believes that’s appropriate because the impact to the tribe has also been severe. As a small, non-gaming tribe with no economic development of its own, the Wiyot Tribe relies heavily on grants, Vassel said, and Cogburn’s actions made it harder for the tribe to be competitive.

“[T]he amount of her embezzlement is nowhere near the cost of the ordeal for the Tribe,” Vassel said. “There were additional costs such as penalties and interest of payroll taxes and accounting cleanup which took a team of forensic accountants, and specialized contractual accountants [to fix].”

The tribe had to pay twice for financial audits for several years because Cogburn’s submissions had been incomplete and non-compliant. The tribe has taken a lot longer than 21 months to recover from Cogburn’s misdeeds, and Vassel said the damage wasn’t all financial.

“Her actions caused real harm to the Wiyot Community and the Tribe continues to recover from that,” she said. “You cannot put a dollar amount on loss of public trust, moral injury, staff attrition or [the] long-term costs of the divisions in the community she created to hide her activities.”

The Outpost attempted to reach Cogburn for comment, leaving a voicemail on a phone number found in the small claims court case file. The message was not returned.

CLICK TO MANAGE