When I was growing up in Humboldt County, I did not learn much from my parents about their lives in Italy; however, I was exposed to the Italian language every day, especially at mealtimes when my father and mother spoke in the dialect of the Trentino region of northern Italy. Although I always spoke to them in English, my memory stored the Italian. By 1964, it was too late to ask questions about the lives my parents had led in Italy — my father had died and my mother was incapacitated by a stroke. Fortunately, over the years. I had worked on my Italian. In 1964, 1 began what was to be a series of trips to Italy to meet several aunts and many cousins, to visit my parent’s birthplace, the village of Cogolo in the Val di Peio at the foot of the Alps, and to learn about the lives of the people I loved. This is their story.

Val di Peio

As it is today, with young men from Mexico risking the journey to America to work in the dairies, it was the dairies — and the timber — that drew European workers: Danes, Finns, Germans, Italians, Portuguese and Swiss-Italians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Usually, a husband or a son emigrated, made some money, returned to the “old country,” often re-emigrating with a wife and other family members. Still others stayed in America, and summoned their friends and family to join them. Such was the case with the immigrants from Cogolo.

Val di Peio, also known there as the “Valletta” (“Little Valley”) is — if one flew as a little bird — 150 miles directly north of Florence in Trentino, the diminutive name given to the western portion of the province of Trento. The Valletta, extending nonh-south for four miles, is the home of five alpine villages. At the valley’s northern point sits the village of Cogolo; behind Cogolo, the land zooms precipitously upwards, past the mountainside village of Peio, to the peaks of the snow-capped Alps, places nearly three miles high, that separate Italy from western Austria.

Along the slope of the western peaks of the Valletta is the border that separates Trento from the province of Lombardy. Lombardy was always a part of Italy; Trento, until the end of World War I, was on the extreme western border of the Austrian Empire. Without assimilating the German language or the culture, the people of Trento had been ruled by — and taxed by — the Austrian Empire for centuries.

Google Earth screenshot of the Val di Peio. Link.

The people were farmers or miners. In the Middle Ages, after the Romans and other conquerors had passed by. the Roman Catholic Church and royalty joined forces and gave the Bishop of Trent authority over the region. No matter who was the ruler, the peasant farmers always bore the brunt of heavy taxes. In 1525, a rebellion the “Rustic War,” pitted farmers against the nobility and the clergy; monasteries and castles were plundered. As a result, each of the villages was given greater local autonomy, and each devised its own constitution, called the “Carta di Regola.”

With the emergence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a national government took over power. Ultimately the mines gave out and the agricultural land decreased its yields. The staples grown by the contadini — rye, barley, and potatoes — became less plentiful, and it was more and more difficult to feed both the family and the cow (or goat) and pig. Money to buy corn meal to make the contadini’s staple meal of polenta was never sufficient. Taxes, whether they were paid in the form of portions of crops, live cows or pigs, or cash, were increasingly burdensome. Cows were raised for milk; heifers and pigs were sold to butchers and wealthy individuals at the annual fairs.

Cogolo village in 2016. Photo: Agnes Monkelbaan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As Austria’s annual assessments increased, the working-age sons of the valley’s families left the region at to find work elsewhere. Some went to other parts of Austria or Italy for seasonal work; some went to Australia for work in the mines and in timber; and some immigrated to the Americas, where there were mines. lumber, and fertile lands. Most of the men from this region who went to the United States to became miners in the copper mines of Colorado or the coal mines of New Mexico.

These young men — Italian in language, Austrian in nationality — had one major advantage over many other immigrants: They were well educated. For this they had the Empress Maria Theresa to thank. It was she who reformed education during her 18th century reign over the Hapsburg Empire. The Empress decreed that all children be schooled through the age of 12 (later, 14). Consequently, when the men left their home towns, their literacy enabled them to maintain written temporal correspondence with their families and information about America flowed generously throughout the region.

It was not unusual for immigrants to make several trans-Atlantic passages. The steamship companies charged about $30 for a steerage ticket; the largest ships could hold as many as 2,000 people in the lower deck for the two-week crossing. Steerage passengers were allowed scant baggage (one trunk, now in a place of honor in my living room, accompanied my parents to America).

All that was needed to embark was a passport or visa, and a quick inspection by the European steamship representative to determine if a person had any illness that would bar him from entrance. After 1892. arrivals in New York City disembarked at Ellis Island and doctors inspected them for signs of “dangerous” diseases or mental deficiency. After 1909, each immigrant parent was also required to show that they possessed the equivalent of $25. After 1917, everyone was subjected to a literacy test — the ability to read forty words in his native language. Unlike today, once someone passed through the immigration procedures and was admitted to the country, they were legal U.S. residents. It would not be until the Immigration Act of 1921, in which quotas were initiated, that the ease of entry diminished.

Vigilio Pegolotti

The eider statesman who began the migration to Humboldt County from the Val di Peio was Vigilio Pegolotti, born in Cogolo in 1871. The Pegolottis were a peasant family that Cogolo’s church records trace back to the 16th century. The family name, so far as can be ascertained, is unique to the Val di Peio. (It may be derived from the valley’s name.) Vigilio went to school until he was 14. Every morning, the teacher led the children in singing the Austrian National Anthem in honor of his Majesty. Emperor Franz Josef I — but they sang it in Italian. When Vigilio grew up, he was an imposing six-footer, who was well-read and loved to quote Dante’s La Divina Commedia. Vigilio also loved to give orders: As his family had more land than most people in Cogolo, he had a certain local importance. Then he got into trouble.

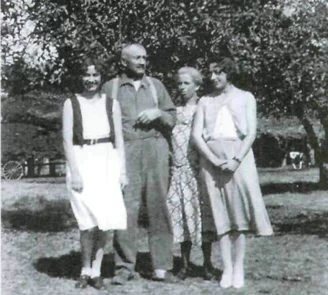

Vigilio Pegolotti family, c. 1930, at Goble Lane, Ferndale. From left to right: Agnes, Vigilio, Maria, Pauline. This photo and those below via the Humboldt Historian.

Each summer, everyone’s cows were herded to a communal pasture. There, the cattle stayed throughout the season, guarded by shepherds. To breed the cows, the community had only one bull. One summer, Vigilio was in charge of the bull — and he allowed it to get loose. Village lore is that, as a result. Vigilio generated ill-will that he could never overcome. While the exact details are lost to history, we can assume that a loose bull impregnated cows in the wrong season. If cows were not bred so that they would calve before winter, they could not give milk throughout the winter, an essential dietary need. The people in the village whose cows were wooed by the loose bull would not easily have forgiven Vigilio’s blunder. Also unforgiving was one of the village’s loveliest women, who had been enamored with Vigilio, but who, because of the bull, refused to marry him. In a small village, such a rejection is shameful. Vigilio, humbled, married instead Maria Bezzi, a plainer woman. A daughter. Agnes, was born in 1910, and a second girl, Pauline, in 1912.

Now forty years old, with a wife and two infant daughters, Vigilio decided to go to America, a judgment that rested most likely on a combination of village disapproval and the need for money to support his family. At the urging of a cousin, who talked of fertile valleys, timber forests, and the Italian colony in San Francisco, in 1912 Vigilio sailed from Le Havre on the SS Chicago, passed through Ellis Island, and took the train to California. His family — due to the outbreak of World War I — was unable to join him for seven years. In San Francisco, regaled by tales of the fertile Eel River Valley, Vigilio sailed north to Humboldt Bay, and soon settled on a rented farm on Loleta’s Cock Robin Island. Vigilio was to be the magnet that ultimately drew other farmers from the Val di Peio to Humboldt.

Giacomo Pegolotti

Giacomo Paolo Pegolotti was born in 1890. the only male in a family of four children. (Before his birth, three sons had died in infancy, including twins named Giacomo and Paolo.) After his school years, he worked with his father Antonio farming small plots of land on the hillsides during the summers, and finding winter work elsewhere, sometimes in an uncle’s store near Ferrara. The family’s funds were sparse; Giacomo most likely had no choice but to emigrate.

His journey began in October 1912, eight months after his cousin, Vigilio, left Cogolo. Giacomo. 22 and unmarried, made his way with three friends to Southampton, England, where they sailed to America on the SS St. Paul. The men went to the coal mines of Raton, New Mexico, a major destination of Italian immigrants since the 1880s. Mining paid well enough money for Giacomo to send money back to Italy to help the family pay their taxes. The mines, however, were dangerous — and so were the living conditions. When he was an old man, Giacomo gave his son, Antone, a small revolver, and told Antone that he bad always kept the gun by his side when he slept in Raton.

In August, 1914, the “War to End All Wars” began on the European continent between the Allies (principally England, France, and Russia) and the German/Austro- Hungarian coalition. Italy remained neutral until 1915. when the government joined the Allies by signing the Pact of London, which guaranteed that at the end of the war Italy would regain the Trentino and the Tyrol from Austria. With that, Italy and Austria became enemies — and the peaceful Val di Peio became a major site of confrontation, the Italians on the Lombardy side of the valley, and the Austrians on the other.

Giacomo, tired of the mines, could not return to his home without being drafted into the Austrian army; gratefully, he accepted Vigilio’s invitation to leave New Mexico and work on his cousin’s dairy.

Vigilio was a hard taskmaster. In those days, milk was placed in ten-gallon cans to be picked up by the creamery truck. One morning, in his haste to get the cans up on the platform. Giacomo, my father, spilled an entire can. Vigilio yelled at my father and asked how it could have happened. My father explained, using another full milk can as an example — and spilled the second can as well. My father never forgot le botte (the blows) he received from Vigilio for his mistakes.

Homesick and longing to begin a family of his own, Giacomo returned to Cogolo in 1920. Eight years earlier, he had been engaged to a village girl who had planned to join him in America. Her father forbid her to leave and she married another. Whether my father knew this before he returned is unclear, but once he arrived in Cogolo women were not scarce: marriage to Giacomo guaranteed a life in America. One who showed particular interest was Ida Migazzi.

The Migazzi family had less of a peasant tradition than most people in the village. Ida’s father had been a blacksmith, a trade long practiced by the family in a region where iron ore had been a commercial staple. The family had a special ranking: the Bishop of Trent had bestowed the royal title of “count” on the head of the family. Not only that, but one branch of the Migazzi family had left Cogolo, settled in Innsbruck. Austria, and produced Christoforo Migazzi, the Cardinal of Vienna at the time of the Empress Maria Theresa and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

It is unlikely that all this meant much to my father; he simply found Ida Migazzi a worthy woman to be his wife. On February 23, 1921, they were married in the crowded little village church, followed by a brief reception at the Migazzi home. Toasts were given with the traditional zabaglione. The reception had to be brief — that afternoon the newlyweds left for Trieste and boarded the SS Belvedere for the journey to New York. In America they rode the cross-country train to San Francisco, and then traveled up to Loleta, to the farm of Vigilio Pegolotti, where they began their life as tillers of the Humboldt soil.

The Paolo Gabrielli Family

Vigilio’s letters to his wile in Cogolo about the good news of Humboldt were shared with everyone in the close-knit society of the Valletta, including the village of Vermiglio, a town near the mouth of the Valletta. Paolo Gabrielli was a shoemaker in Vermiglio who had fallen in love and married, in 1907, one of Vigiiio’s cousins, Felicita Pegolotti. Felicita had come to the Gabrielli home to learn the skill of sewing from Paolo’s sister. In 1914, when Paolo and Felicita had two little boys and an infant daughter, Paolo determined that he, too, should go to America to earn more money for his family. The news from Vigilio about the lush Eel River Valley was appealing. Paolo emigrated to Ferndale in February 1914 with the intention of sending for his wife and children shortly. What he didn’t know was that with the Great War, all immigration would cease and, even worse, the war would bring tragedy to his town and to his family.

The Paolo Gabrielli Family (c. 1945): Left to right: Back row: Paolo, Felicita, Virgilio (Fr. Gino): Front row: Louis; his son, Donald; and his wife, Alma.

When Italy and Austria declared war in 1915. the Austrians feared an attack by the Italian army from Lombardy to the west. To set their defenses, the Austrians placed massive gun emplacements on the snow-and-ice-covered eastern flanks of the Valletta. Naturally, the Italians followed with similar defenses on the western Lombardy ramparts. For three years, the armies bombarded each other with severe regularity in what would become known as la Guerra Bianca, the White War.

For the Austrians, cannonading was not enough; they feared surprise attack by infiltration at night from the Lombardy hills, over the Passo Tonale, and down what had been the Austrian Imperial Highway. This road went through Vermiglio. the closest town to the Italian border, and past the mouth of the Valletta on its way east along the Val di Sole. Since the entire area of the Valletta was lull of Italian sympathizers, the Austrians first considered deporting everyone from the region. Astute cooperation of the clergy and town leaders with the military saved everyone except those in Vermiglio.

The fearful Austrians first drafted all the healthy men of the village into the army, and then assembled the remaining villagers — old, young, healthy, or infirm — to begin a long journey by foot and by train to a refugee camp at Mittendorf, outside of Vienna, hundreds of miles away. Felicita Gabrielii and her three children — two small boys, Virgilio and Louis, and an infant girl, Paolina — were among the evacuees. Contagious diseases spread quickly through the close quarters in the wooden barracks; among the many from Vermiglio who died was Paolina.

After the war ended in 1918, the province of Trento reverted to Italy, and the survivors of Mittendorf, including Felicita and her two sons, returned to Vermiglio. A year later, the two joined Paolo in Ferndale. (Virgilio Gabrielli. the little boy who had suffered in the Mittendorf concentration camp, became a Catholic priest. Known to friends as “Father Gino,” he was the second man from Ferndale to become a priest; called to the Sacramento diocese, he served nine parishes in three Sierra Nevada foothill counties.)

The Migazzi/Dieni Family

The foundation for the fourth of the families to come from Cogolo to Humboldt was set a month before the marriage of my parents, when in January 1921, Virginia “Pia” Moreschini set out for the United States.

Pia’s parents had had eleven children, but only four lived to adulthood — a son and three daughters. To help grow the crops, the young girls worked as hard as the men. Then along came the White War. As happened to many young women of the Val di Peio, Pia was conscripted by Austrian officers to bring food to the soldiers at night. Cannons fired across the Valletta during the day. At night, the ice-cold brilliance of massive searchlights attempted to ferret out any secret activities. Pia and other young girls knew mountain trails; they followed the dark trails up to platforms at the base of aerial trams. There, they deposited food to be transported via funiculars to the often frostbitten Austrian troops in their bunkers. Meat was seldom available, since the few goats and cows were needed milk; potatoes, barley soup, and rock-hard rye bread were the staples for the contadini and the Austrian soldiers. As Pia brought food over icy trails to the Austrian troops, she must have prayed for some miracle to get her out of the the Valletta.

Her prayers were answered — three years after the war ended — when 38-year-old Achille Migazzi, who had left Cogolo in 1905 for the United States, sent word back to his family that he was ready to marry. Was there any woman there who would come to be his wife in Idaho? Twenty-eight-year-old Pia didn’t hesitate — for two years already she had heard about the wonderful United States from Felicita Gabrielli, her first cousin, in Ferndale.

Pia wrote to Achille (also a second cousin of my mother) and made arrangements to be his bride. With sad goodbyes to a family she would never again see, Pia left Cogolo for Genoa to board the ocean liner Re D ‘Italia and begin her journey to Pocatello. There on March 4, 1921, she and Achille were married. And it was on the marriage license that, for reasons unknown, the family name officially exchanged an “i” for an “e,” and became Megazzi.

Once settled with her husband and working the farm they had rented, Pia sent word to her cousin Felicita of her happiness. In the next ten years, Pia and Achille entered a variety of farming ventures from Utah to Oregon, while raising their three children — Felix, Rose, and Henry. Then, in the Depression years, times were hard. Pia and Achille borrowed money to buy a dairy in Ontario, Oregon, along the Snake River; not long after, in March, 1931 almost ten years to the day of their marriage, Achille dropped dead of a heart attack. Pia, completely distraught, suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be taken to the hospital while nuns took care of the children for many months. Meanwhile, the ranch was foreclosed and sold.

After her recovery, Pia, in a story she was to tell often in later years, went to the bank of the Snake River, took out the remaining few coins she had in her pocket and tossed them into the river, saying, in Italian: “Might as well start from the beginning.”

When Pia was well enough to find employment, she took advantage of Prohibition and became a runner for bootleggers, delivering the goods hidden under the blankets of a baby carriage.

Her good-hearted cousin, Felicita, however, was looking for an opportunity to become a matchmaker, and for she found it in Emanuel — Manuel — Deini, a bachelor from the Piedmont area of northern Italy. Manuel was a farmhand for Hans Hansen in Port Kenyon, and often visited the Gabriellis on their Centerville ranch, a mile from Pacific Ocean. Very likely the reason for Manuel’s frequent visits involved sampling “grappa,” the hair-raising Italian whisky made from the distillation of grape residues after the preparation of legal wine. Paolo Gabrielli had added this illegal venture to the roster of his dairy activities. The still was hidden under the boards of his chicken house.

Felicita convinced Manuel to visit Pia in Oregon. The bachelor took the advice. He had more than one reason to seek a wife — his 93-year-old mother, Fortunata, had taken up residence with him. Fortunata spoke no English and she loved to smoke dark Italian cigars. In Italy, she had survived both the birth of thirteen children and an avalanche that had wiped out her home and all the family possessions.

Pia and Manuel were married by a county judge in Vale, Oregon on December 12, 1934, and they returned to Ferndale, where Reverend J. Gleeson validated their marriage in the Assumption Church two weeks later. The Deini house on Herbert Street now became the home of Pia, Manuel, the three Megazzi children, and Fortunata, the mother-in-law. When Fortunata reached a hundred, Ferndale had a celebration at the Village Club. By that time, Pia’s care for Manuel’s mother had gained the attention of the Ferndale Enterprise, which reported: “Much of the elderly lady’s comfort and happiness is due to her daughter-in-law’s kindnesses and attention,”

The Antonio Ravelli Family

In 1921, the man who would bring the fifth family from the Valletta arrived in Ferndale in the person of Antonio Ravelli, Vigilio’s first cousin. Ravelli was from Comasine, a village hugging the western flank of the Valletta, a half-mile from Cogolo. Trained as a shoemaker, Tony had been in the Austrian army for several years before World War I began. After discharge, he helped his family by working in Broken Hill, the largest mining center in Australia, where, for six years he pushed carts of silver and lead ore along tracks in the mineshafts.

Tony had kept in touch with his cousin Vigilio, who welcomed him into the United States and gave him temporary work on his ranch. Later, Ravelli moved into the redwood forests as a sawyer, paid off his debts, and earned enough money to open Square Deal Shoe Repair in Eureka. In 1928, Tony’s brother Basilio, took over the shop for six months, so Tony could return to the Val di Peio and find a wife. There, in a restaurant in the town of Male, he spotted Maria Gemma Angeli, the hostess. After a short courtship, they manned; Tony returned to Eureka and Gemma joined him a few months later. They had two children, Doris and Bruno, who were raised in the family home on F Street in Eureka.

Of all the families, only my parents, Giacomo and Ida Pegolotti, ever returned to Italy — thirty years after their zabaglione nuptial toasts.

###

Author’s note: There are two primary sources for this article: (1) information from visits to the Val di Peio, especially oral histories from cousins that I recorded in November 1995, as well as elderly Cogolo residents who are relatives of the “five families. ” (2) information front members of the “five families”: Donald and Donna Gahrielli. Kathryn Griffith and the late Rose Megazzi Griffith, the late Pauline Pegolotti Mayer, Henry Megazzi, my brother Antone Pegolotti. Bruno Ravelli, and Doris Ravelli, I am most grateful to them all.

Members of four of the five families in front of Pegolotti ranch, Waddington Road, 1946. left to right: Standing: Virginia “Pia” Megazzi Deini, Gemma Ravelli, Paolo Gabrielli, Manuel Dieni, Louis Gabrielli, Alma Gabrielli (wife of Louis), Dorothy Pegolotti (wife of Antone), Ida Pegolotti, Antone Pegolotti, Giacomo Pegolotti, Doris Ravelli. Kneeling: James Pegolotti, Donald Gabrielli (son of Louis and Alma), Bruno Ravelli.

###

Jim Pegolotti graduated from Ferndale High School in 1951. He received a B.S. in chemistry from St. Mary’s and a Ph.D. in chemistry from U.C.L.A.. After years as a professor of chemistry and a college dean at Saint Peter’s College in Jersey City, he served as dean, then librarian, at Western Connecticut State University. He retired in 1999. His first book — Deems Taylor; A Biography — was published in 2003 by Northeastern University Press.

The story above is excerpted from the Winter 2003 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE