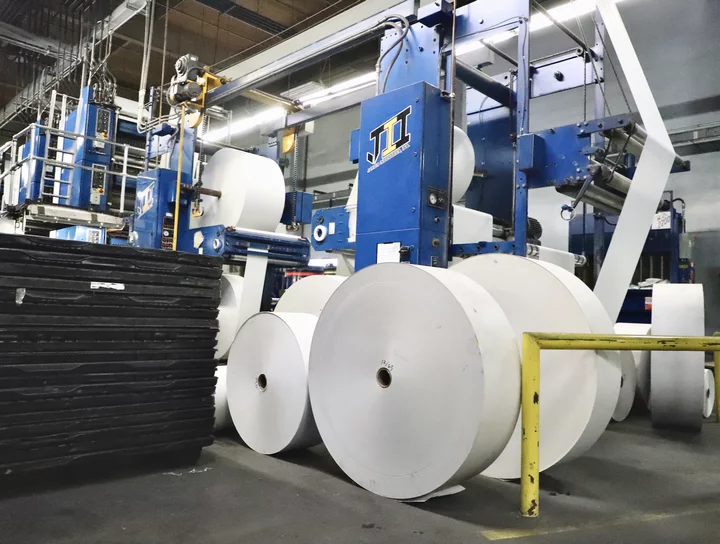

The Western Web printing press on the Samoa Peninsula was built in 2005 to print the Eureka Reporter. | Photos by Andrew Goff.

###

When Western Web came to Humboldt County in 2005, it did so quietly — furtively, even. The state-of-the-art printing plant, assembled with brand new equipment inside a cavernous old mill building on the Samoa Peninsula, was established for the sole purpose of publishing the Eureka Reporter, an upstart daily newspaper founded by Robin P. Arkley II in order to challenge the Times-Standard.

Arkley, Eureka’s brash and well-connected commercial real estate magnate, set off a fiercely fought, if short-lived, old-fashioned newspaper war with Humboldt County’s 150-year-old daily. As a 2006 SFGate story recounted, the Times-Standard had “seemingly incurred Arkley’s considerable wrath when it failed to endorse his wife Cherie’s failed bid for Eureka mayor in 2002, a race Cherie Arkley lost by fewer than 50 votes.” (Arkley denied that this slight was his motivation for starting the paper.)

I got hired at the Times-Standard in the midst of this newspaper war, and the competition between the dueling dailies was invigorating. The news coverage at both publications benefited from the rivalry, and the two editorial staffs were robust, especially by today’s industry standards.

But there was no competition when it came to the quality of the actual papers — meaning the physical newsprint and ink. The reporters and photographers at the Times-Standard would pick up a copy of the Eureka Reporter (it was free) and jealously thumb through its pages, which were thicker and whiter — resulting in richer, sharper images — than those running our own work. Back then, the T-S was printed in-house, on equipment that was much older than the fancy new machines across the bay at Western Web.

About that name: Why would a printing plant go by the online-sounding, geographically vague moniker of Western Web? They chose the name “in order to sneak up on potential customers out of our area without the burden of explaining why it made sense to print in Eureka,” the company explains on its website.

Arkley encouraged Western Web President Steve Jackson to go out and recruit commercial clients to subsidize the cost of printing the Eureka Reporter, and he did so. The company’s first customer, signed in 2005, was the North Coast Journal. It was soon followed by other newspapers, including the Arcata Eye, the McKinleyville Press, the Ferndale Enterprise, the Humboldt Independent and Cal Poly Humboldt’s student newspapers, the Lumberjack and El Leñador.

Western Web also prints tour guides, banners and glossy magazines such as J. the Jewish News of Northern California (distributed biweekly in the Bay Area), Latitude 38 (a sailing publication), and, until this month, a variety of special publications from the North Coast Journal, such as the Humboldt Insider, My Humboldt Life and its annual Wedding Guide.

In a recent interview, Jackson recalled the company’s optimistic early days. Prior to coming to Humboldt County he’d been working at Grant Printing in San Francisco. Arkley’s company, Security National, brought Jackson up to consult on selecting a building and buying equipment for the new press, and eventually Arkley asked if he’d be interested in running the place. He’d grown up in the tiny Trinity County community of Douglas City, so coming to Humboldt appealed to him on a personal level. And the professional opportunity was too good to pass up.

“This was a chance to build my own plant from the ground up, and I took it,” Jackson said.

But 20 years later, does it still make sense to print in Eureka? Printing presses have been closing at a rapid clip across the country in recent years. Since 2005, more than 3,300 newspapers have ceased publication. Locally that includes the Eureka Reporter, which shut down during the 2008 financial crisis; the McKinleyville Press and Arcata Eye, which merged to become a single publication, the Mad River Union, in 2013; and, most recently, the SoHum-based Independent, which published its final issue last summer.

Worse yet for Western Web, three weeks ago its oldest and largest customer, the North Coast Journal, left, choosing to have its papers and various other publications printed out of the area. In an April 3 letter to readers headlined “The Price of Print,” Journal owner and publisher Melissa Sanderson cited skyrocketing print costs and said, “When we received notice that possible tariffs on Canadian paper would further increase our printing bill, we explored every possible solution, negotiating with Western Web, evaluating alternative options and considering cost-cutting measures.”

Jackson said there was more to it than that — namely, a months-long dispute about the Journal’s unpaid invoices. By the end of last month, the Journal’s balance sheet — which includes tallies for sub-customers such as the Ferndale Enterprise, the Fortuna Chamber of Commerce and Murphy’s markets — was $120,377.91. (Sanderson disputes that figure and notes that much of it was not yet due, per the terms of their agreement. More on that below.)

On top of that, Jackson said, the Humboldt Independent owed Western Web about $50,000 when it shut down, a debt he doesn’t intend to try to collect.

“I worked with them for a long time,” he said. “They fell behind every week for months on end. … I said I can’t keep doing it, and they decided to stop publishing. I know that newspapers are on the way out — printed newspapers — but it really hurt.”

Western Web also prints the Trinity Journal, and Jackson said that publication has also fallen behind on its bills.

“I grew up in Trinity County … . That’s where I learned about newspapers,” he said. “I was reading the Trinity Journal when I was a kid; it got delivered to our house. I really enjoyed printing them the last 20 years.”

But he said Western Web’s finances have reached the point where the business simply can’t carry this level of unpaid debt for months on end. On a recent trip to San Francisco, Jackson stopped by the offices of J. (the Jewish news magazine) and told them that his company is in a very difficult spot.

“I encouraged them to explore other options [for printing],” he said.

A few moments later, Jackson quietly remarked, “Our closure is inevitable.” However, he quickly backpedaled, saying, “I haven’t given up.”

But he’s worried about having to cut some production staff due to the reduced work volume. He’s worried about the Trump administration’s 25 percent additional tariffs on Canadian goods, since much of the newsprint Western Web buys comes Canadian-grown trees. (“Canada’s where all the trees are,” he said.) He worries about the future of his employees, many of whom have been working with him for decades but are not set up for retirement. And he worries about all the local publications that still rely on Western Web. What will they do if it closes?

“I’m just tired,” he said. “I don’t have the energy to fight back. But I still haven’t given up.”

The North Coast Journal situation

The Journal’s fallout with Western Web had been building for more than a year, but it came to a head at a meeting on March 17. Jackson had notified all of Western Web’s large customers that he’d soon have to increase prices due to tariffs, though he had not yet done so. (Nor has he to date, he told the Outpost.)

At the March 17 meeting, which took place at Western Web, Sanderson told Jackson and Western Web Production Manager Mike Morris that she’d gotten a quote from another printer for roughly half the cost of what Western Web was charging, according to Jackson. He was somewhat incredulous, given that most commercial printers offer pretty comparable rates, but he told Sanderson something along the lines of, “If you truly have a price that is half, you should take it.”

She did. Eleven days later, she emailed Jackson to thank him and the team at Western Web for their dedication, craftsmanship and many years of service to the Journal but said they’d no longer be using the local company for their weekly newspaper jobs.

For the sake of disclosure I should note that I worked at the North Coast Journal from 2008-2013, under previous publisher Judy Hodgson, who co-owned the paper with Carolyn Fernandez. During my time at the T-S and the NCJ I worked with several of the Journal’s current staff members, including News Editor Thadeus Greenson, Arts & Features Editor Jennifer Fumiko Cahill and Digital Editor Kimberly Wear, whom I consider colleagues or even friends, though we don’t hang out socially.

Sanderson declined to be interviewed in person or over the phone for this story, but she agreed to answer questions via email. The only question she didn’t answer was where the Journal is now being published. Asked why she didn’t want to disclose that information she replied, “It isn’t necessary.”

Both Jackson and Sanderson expressed bitterness about the breakup. Jackson forwarded the Outpost some emails from the past two years and said he simply couldn’t carry $120,000 in debt on the Journal’s behalf for months on end.

Sanderson, meanwhile, said the Journal was operating with Western Web under the same terms it had operated under for years, adhering to an arrangement that predated her purchase of the Journal on April 1, 2021. The higher debt balance was a byproduct of a dramatic increase in printing volume from the Journal, she said. Under her ownership, the company had expanded its special publications, such as My Humboldt Life, purchased the Ferndale Enterprise and picked up contract work with outside organizations such as the Fortuna Chamber.

“[W]e do upwards of half a million dollars’ worth of business with Western Web annually, depending on the year, always carrying a balance since before my time,” Sanderson said. And the Journal always pays what it owes, she said.

At 70 years old, Jackson has suffered a variety of health issues in recent years, including a burst appendix that required him to be placed in an induced coma, as well as Parkinson’s, which he’s had for more than a dozen years. He’s the person in charge of keeping track of Western Web’s accounts receivable, but due to his health he’s had periods of absence.

In July of 2023, following one of these periods, Jackson sent Sanderson an email with the subject line “Alms for the poor.”

“You have been great about paying on time and I appreciate it,” Jackson wrote to Sanderson, “but costs keep going up and I am facing a cash flow crisis at the end of this month due to overlapping paper and ink orders. I could really use your help in catching up your account as much as possible. I show you have $69,172.78 balance on your account.”

The Journal’s longstanding arrangement with Western Web was for “net 60” payment terms, meaning its bills were due 60 days after the invoice date. Technically, Jackson said, the terms of the deal were actually “net 30” (bills due after 30 days) but longstanding practice had been to allow up to 60 days for repayment.

In response to that July 2023 email, Sanderson said she’d make sure a payment was headed to Western Web the following Monday, though she added, “I can’t keep printing with the bills so high. It’s increased by over 40% since I bought the paper and I have to relook at stuff. This print expense is almost as much as my payroll now.”

According to Jackson, Western Web has only implemented one rate increase for the Journal — a seven percent hike in 2022. The 40 percent increase cited by Sanderson was mostly a reflection of increased printing volume, he said.

The billing dispute resumed early this year and quickly got testy. In a Feb. 11 email, Jackson told Sanderson that the Journal’s balance now exceeded $113,000, some of which was more than 60 days old.

“After promising to catch up when we last spoke, you have fallen further behind,” Jackson wrote.

He also said Western Web needed to implement a change. The Journal is printed on 24-inch newsprint. However, all of the other print jobs Western Web runs during that time slot use 22-inch paper.

“Our cash flow situation is so severe we cannot afford to carry inventories for both sizes,” Jackson wrote in his email. For the Journal to keep publishing at Western Web, it would need to make all future issues smaller. The tone of his email was civil but terse. “I know it is terrible out there, but I have no other options,” he said.

In her reply, Sanderson again noted how much more volume she’s doing with Western Web, adding that the paper’s printing bills now accounted for more than a third of the Journal’s budget.

“You will have to work with me over the next few months otherwise, I may have to take drastic measures and remove some print products from the community,” Sanderson wrote. In a follow-up email she said, “We are paying you as fast as we can.”

Interviewed via phone last week, Jackson said he’s frustrated by how the Journal left. Sanderson’s email delivering the news was sent after 4 p.m. on a Friday, when his staff had already placed materials on the press to print the paper the following Tuesday. And he has lots of leftover paper and ink that he purchased to publish future issues.

“I’m still paying off bills from the North Coast Journal and yet I have no income at all [from them] since March 21,” the last time Western Web received a check, he said. “They’ve just ignored us since.”

Sanderson, meanwhile, said Jackson didn’t budge when she told him about the printing deal she could get elsewhere. (Jackson said he asked to see a copy of that quote but Sanderson never provided one.)

“Steve made no effort to negotiate a more competitive price and said, ‘If you can get that price, go with my blessing.’ I took him at his word … ,” she said. “If WW had been able to partner with a paper producer that could come close to the estimates we got elsewhere, we’d still be printing in Samoa.”

She also reiterated that the Journal will pay what it owes to Western Web in the coming weeks, per the longstanding agreement.

Western Web buys its newsprint from Inland Empire Paper Company in Spokane, Wash. That company maintains and harvests its own forests here in the U.S., but still, about half of Western Web’s newsprint stock — and all of its glossy paper — comes from trees grown in Canada.

Jackson said Western Web has an energy-efficient arrangement with Inland Empire, hauling its paper supply down here to the press in Samoa and then sending back the press’s waste — trimmed borders, scraps, etc. — to be converted into recycled paper.

The future of newspapers

Over the course of two phone conversations, Jackson’s general demeanor was of pained resignation. He recalled seeing last year’s April Fools’ edition of LoCO Pollz, which joked that the Lost Coast Outpost would soon launch a daily printed edition.

“It should have made me cry,” he said. “It was a joke but it’s also the reality. It’s crazy to open a newspaper now.”

He allowed that some alternative newsweeklies are still thriving, though he noted that once-vibrant ones, like the Sacramento News & Review and its sister publications in Chico and Reno, are gone.

Sanderson maintains her faith in print. “[O]therwise I wouldn’t have bought two newspapers and the Insider and started the My Humboldt Life publication,” she said. “But thriving requires adaptation in terms of things like printing costs and focusing on the needs of readers and advertisers that aren’t being met elsewhere.”

She also said that the Journal recently reduced its circulation by almost 14 percent, decreasing from 18,000 issues per week to 15,500. The Journal is also moving its offices from an upstairs spot in the heart of Old Town to a building near the corner of Fifth and J streets, across from the Humboldt County Courthouse.

Jackson reiterated that he hasn’t given up on Western Web, though he has tried and failed to find a buyer for the business.

“If I close the doors, I’m not sure I can sell the equipment for anything other than scrap metal,” he said. The Times-Standard dismantled its printing press five years ago, sending most of its components to the junkyard.

“I’m doing the best I can,” Jackson said. “I just have to do it until it’s over.”

The Western Web building in Samoa. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

CLICK TO MANAGE