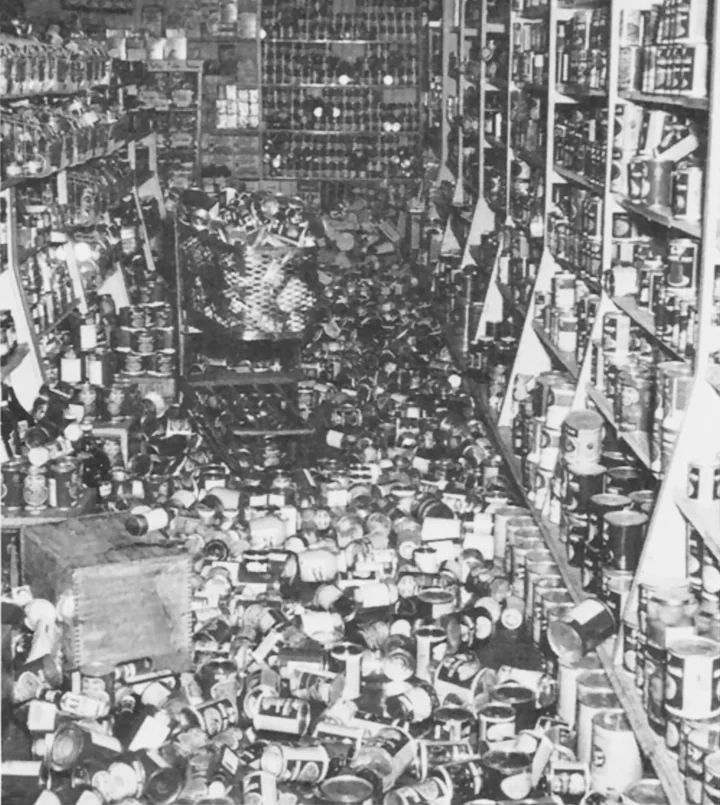

The aftermath of the Dec. 21, 1954, earthquake, as seen from Fourth and F streets in downtown Eureka. | Photo contributed by Lori Dengler via the Humboldt Times.

###

Just before noon on Dec. 21, 1954, a 6.5-magnitude earthquake rocked northern Humboldt County, toppling chimneys, shattering storefront windows, buckling old buildings and causing irreparable damage to Eureka’s old courthouse. The initial jolt triggered the collapse of a log deck in Korbel, killing an employee at the mill. Fifty others were injured, and countywide damages were estimated at $2 million.

While destructive, the earthquake itself wasn’t unprecedented — the North Coast region has experienced four dozen earthquakes of a magnitude 6.0 or greater since 1900, according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). What set this one apart was its unusual inland location and the intensity of its shaking.

This so-called “enigma” earthquake was long thought to have been the only quake in our historic catalog centered on one of our region’s many surface faults, until now.

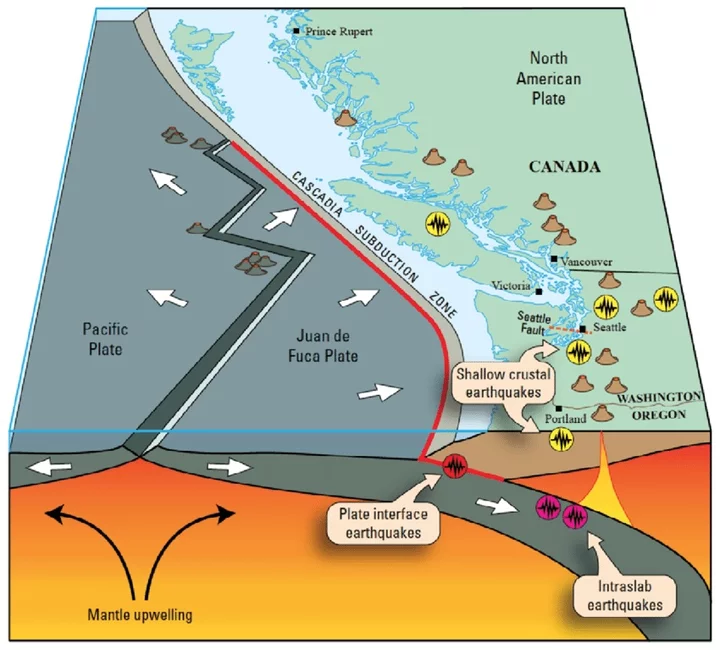

A newly published study in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America revealed that the earthquake “most likely” took place approximately seven miles beneath Fickle Hill on the infamous Cascadia Subduction Zone interface, a major offshore fault line that runs from Northern California to British Columbia.

“One of the things that’s so unusual about the Cascadia Subduction Zone is how quiet it is,” said Lori Dengler, emeritus professor of geology at Cal Poly Humboldt and co-author of the study. “We don’t see small or moderate earthquakes on it. There have been a few very small magnitude twos and threes that appear to be close to the interface … but we’re talking about really, really small earthquakes. It never occurred to me that [the 1954] earthquake was actually an interface event, and now it looks like it was.”

The finding prompts new questions about seismic activity along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which is capable of producing “great earthquakes,” defined as a magnitude 8.0 or greater. The last time the Cascadia Subduction Zone produced a “great earthquake” was in January 1700, when a 9.0-magnitude quake ruptured from the Cape of Mendocino north to Vancouver Island, causing coastlines to drop by several feet and an “orphan tsunami” to crash into Japan.

Before this research, seismologists didn’t know that the Cascadia Subduction Zone was capable of producing “moderate” earthquakes, ranging in magnitude from 5.0 to 6.9.

“What we now know is that this Cascadia Subduction fault can have moderate-size earthquakes,” said Peggy Hellweg, a retired seismologist at UC Berkeley’s Seismological Laboratory and lead author of the study. “It may be a relatively rare occurrence, but it can happen.”

Uncovering 70 Years of Seismic Data

Most “moderate” or “strong” earthquakes we feel here in Humboldt County originate way out in the ocean near the Mendocino Triple Junction, a tectonic boundary where the Juan de Fuca/Gorda, North American and Pacific plates meet.

Since 1950, the USGS has recorded 28 earthquakes in our region that exceeded a magnitude of 6.0. “Eight were centered in the triple junction region within 25 miles of Cape Mendocino,” Dengler wrote in a July 2024 column published in the Times-Standard. “Thirteen were in the Gorda plate offshore of Humboldt and Del Norte Counties. Six were Mendocino fault quakes, on the plate boundary that marks the southern edge of the Gorda plate. There is one enigma.”

The enigma is, of course, the Fickle Hill earthquake of 1954.

When the shaking began that December morning, it triggered nearby seismic stations in Arcata, Eureka and Ferndale. Preliminary data indicated the earthquake’s epicenter was onshore, somewhere within a huge “cloud of probability” between Arcata, Blue Lake and Dinsmore.

“Even with the seismic networks of that time, it was clear it was constrained to being onshore,” Dengler said. “The genesis of this project was: Can we figure out exactly where it was? Can we figure out if it was deep? However, our ability to constrain depth in 1954 was not very good. Now, obviously, we can’t go back and rerecord the earthquake, but what we could do is find all the records that did record it and use modern techniques to get a much better sense of the geology.”

Dengler had discussed the enigma earthquake with Hellweg many times over the years. When Hellweg retired a few years back, she decided it was time to take on the project. She dug through decades of paper records looking for any information relating to the December 1954 earthquake. Once she had what she needed, she passed it on to another researcher to be digitized and analyzed.

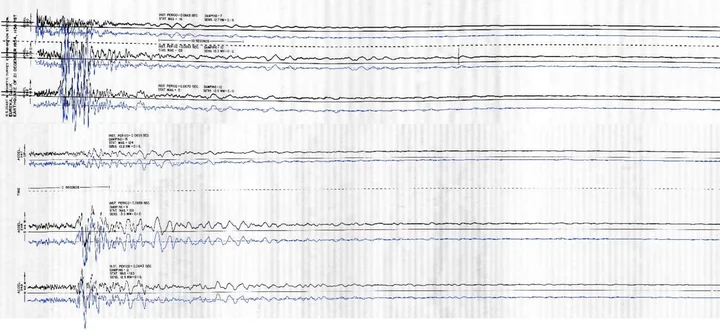

Scans of paper three-component accelerograms from Eureka and Ferndale seismic stations. | Image contributed by Peggy Hellweg.

While Hellweg scoured 70-year-old documents, Dengler conducted in-person interviews with people who had lived through the earthquake. “It was amazing how vivid their recollections were,” she said.

“There was the four-year-old boy who was sitting at his kitchen table and watching a cup and a saucer vibrate along the countertop and then stop and not fall off. It’s one of his earliest memories, and we can actually tell [a lot] from that story,” Dengler said. “First of all, it was high-frequency motion. If it had been low, slow motion, it wouldn’t have vibrated; it would have just sat on the counter. We can also tell that it wasn’t super strong at his location because it didn’t go flying off the counter.”

Dengler also recounted the story of an 11-year-old girl who was riding her bicycle around Eureka with a friend when they were “suddenly stopped in their tracks” because the shaking was so strong.

“They could see the ground rolling like the ocean and see chimneys toppling,” Dengler said. “One thing she said that really stuck in her mind was the woman in her bathrobe and her curlers racing out of her house onto the street, which, in 1954, was definitely not something you did. … It was fascinating, not only to get a sense of the pattern of shaking, but that the pattern of shaking supported this moderately deep — not super deep and not super shallow — earthquake.”

The aftermath of the 1954 earthquake at the old Arcata Market. | Photo contributed by Lori Dengler via the Arcata Union.

When Dengler first began her research, she theorized that the 1954 earthquake occurred within the subducting Juan de Fuca/Gorda Plate, where we tend to have strike-slip earthquakes.

“That would have been my guess … because that’s where we see the most earthquakes,” she said. “I would have bet that this was a moderately deep strike-slip earthquake, but it wasn’t. … It was definitely what we call a ‘thrust’ earthquake, where one side is shoved up over the other.”

There are only two places on the North Coast where thrust earthquakes can occur. “One is in the faults really near the surface,” Dengler said, referring to a series of exposed fault lines that trend northwest, parallel to mountain ridges. The Little Salmon Fault, for example, runs through the College of the Redwoods campus and has several parallel fault strands running through the Mad River Fault Zone.

The other place where thrust earthquakes can occur is, of course, the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

Cross-section of the Cascadia Subduction Zone. | Graphic: USGS

‘It’s Certainly Opened Our Eyes’

What does this new research mean for our understanding of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, you ask?

“The results [of this study] have contributed new insights into its source, which is quite possibly the Cascadia subduction interface, making the 1954 earthquake the first large event to be documented in the instrumental era centered on the locked boundary,” the study states. “[O]ur study of the 1954 Fickle Hill earthquake provides a template for the reexamination of other significant earthquakes of the pre-digital age.”

In simpler terms, seismologists now know that the fault line is capable of producing moderate earthquakes, not just catastrophic events.

“The Cascadia Subduction Zone is about 650 miles in length. … [The 1954] earthquake caused slip on a patch [of the fault line] that was about 10 miles, maybe even less than that,” Dengler said. “One side slipped up and over the other, only on the order of a foot or so. For a magnitude 9.0, we would expect a rupture of 650 miles long. One side would be shoved over the other on the order of 30 to 60 feet.”

“It’s certainly opened our eyes,” she continued. “It’s causing a lot of discussion in the scientific community, which is exactly what we wanted to do.”

The work isn’t quite finished. Dengler is still looking for eyewitness accounts of the 1954 earthquake. Hellweg will continue collecting records and seismic signals to better understand the complexities of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, and whether the next “great earthquake” could be preceded by a foreshock (a small to moderate earthquake that occurs before the big one).

At several points during our conversation, Dengler emphasized that this study “does not in any way change our perception of the hazards” posed by a rupture on the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

“One magnitude 6.5 earthquake 71 years ago is not going to relieve stress on the interface, especially since it only slipped a 10-mile zone,” she said. “It’s completely negligible in terms of the general picture of Cascadia.”

If you’ve read Kathryn Schulz’s article “The Earthquake That Will Devastate the Pacific Northwest,” published in The New Yorker in 2015, you are almost certainly already terrified of the impending catastrophe that awaits within the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Among other frightening things, the article claims that Cascadia is “long overdue” for a rupture, an assertion Dengler passionately disputes, given that geological evidence indicates the Cascadia Subduction Zone ruptures every 200 to 800 years.

Rather than taking a fatalistic approach to the inevitable rupture of Cascadia, Dengler encouraged residents and local governments to start preparing for a massive seismic event sooner rather than later.

“Thinking ‘Oh my god, we’re all going to die!’ means ‘I’m just not going to think about it because there’s nothing I can do to prepare. That’s exactly the opposite of what you want to do,” Dengler said. “What you do and what your community does beforehand will make a huge difference in terms of how comfortable you are in the hours, weeks and months afterwards, and how quickly your community can recover and kind of get back to a new normal.”

Dengler is still looking for eyewitness accounts from the 1954 earthquake. If you or someone you know lived through the earthquake — or if you happen to have old newspapers, church records, diaries, or anything from that time period — give Dengler a call at the Humboldt Earthquake Education Center at 707-826-6019 or send an email to kamome@humboldt.edu.

###

###

Want to prepare you and your family for an earthquake or tsunami? Check out the links below for local emergency preparedness tips.

CLICK TO MANAGE