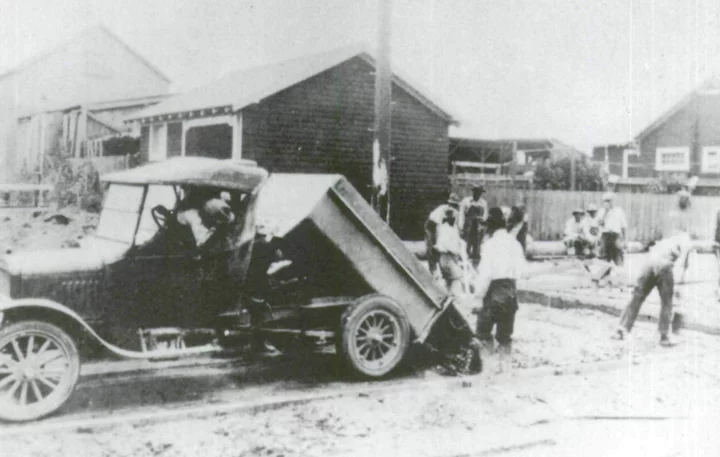

Men from the Englehart Paving-Construction Co. poured concrete on Henderson Street with the help of a Model-T dump truck. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

Cement was used by man when he first started to build. The Assyrians and Babylonians used a clay for cement. The Egyptians used lime and gypsum cement in the building of the pyramids in 2500 B.C. The Greeks made further improvements in cement and the Romans perfected a hydraulic cement, called pozzolana, in their buildings and roads, using a mixture of slacked lime and volcanic ash from Mt. Vesuvius.

The use of cement is not new, but improvements have been made in this country with the discovery of a stone in Madison County, N.Y., which resembled a stone found on the Isle of Portland. In 1824 Joseph Aspdin patented a hydraulic cement made from this stone, hence the name “Portland cement.”

The builders in Eureka and Humboldt County have been using concrete since the first settlers arrived. All they waited for was the cement which was shipped in by ships (there has always been plenty of good sand, gravel and water locally).

For many years before the 1920s, gravel and sand were hauled by horses and wagons from the mouth of Elk River, where the gravel was shoveled on to the wagons by hand; these wagons held a cubic yard. A cubic yard of gravel weighs over 3,000 pounds, which was a heavy load for a team of horses to pull. These wagons were heavy, the bottom of the box was formed of 12 2x4s, making it 3 feet wide and about 12 feet long. These 2x4s had rounded handles formed on the back end, and side boards built out of 2x12s. The end boards were 9 feet apart, allowing the wagon to hold 27 cubic feet.

When the loaded wagon arrived at the job site, the side boards were pried off, some gravel would fall, then each 2x4 would be turned by hand, dumping the gravel on the ground. The side boards would then be replaced and the team would head back for another load. There is one of these gravel wagons at the Ferndale Museum, though not in very good shape.

As I recall, two of the early teamsters who hauled gravel to the Eureka job sites were the McLaughlin brothers, Ben and John, founders of the Eureka Sand and Gravel Company.

Concrete was mixed by hand using a mortar box and shovels. Usually two men were involved in the process, one each side of a box about 6 to 8 feet long, 4 feet wide and with sides 8 inches high. This box would first be placed along side of the gravel pile. Each man would then throw in so many shovels of gravel and then so many shovels of cement (the amount of cement depended on how “rich” the mix was to be). The mixture would then be shoveled from one end of to the other and turned over several times until it was thoroughly mixed. Some water would then be poured on and again it would be turned over until at last it was concrete.

This mixture would be shoveled into wheelbarrows, wheeled to and then dumped into forms or into a specific place such as a floor or sidewalk. Next would come the job of finishing with wooden floats and trowels. If the project was a floor or sidewalk, the base would be poured first; this would be kept about 1/2-inch low when it was screeded off. Then a mixture of sand and cement was poured on top. This was then finished to a nice smooth surface and, if it was a sidewalk, was marked off in squares.

Some times the base was left until the following day, when the topping would be applied. In case of rain or a freeze, this had to be covered to protect it until it was set up. And then of course there were always people who wanted to scratch their name or initials in the new on surface. Though humorous to the “artist,” the next day it would be a job to get the scratches out. Once in a while someone would walk right down the middle of newly poured concrete, which would take a lot of work to fix.

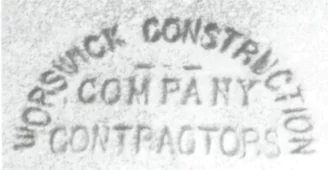

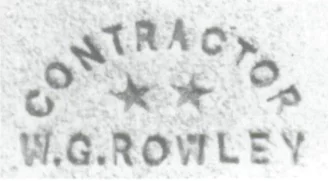

Some of the old-time cement contractors marked their cement work with their names by using a brass casting. These were usually a half circle about 12 inches in diameter. Most of these men are gone now but their names are still stamped in various places around Eureka, especially on old concrete sidewalks.

Many of these old concrete sidewalks are still in use today though some are disintegrating as the salt content from the Humboldt Bay water causes the concrete to lose its strength.

In the early days when there was plenty of good redwood lumber available. Most of the sidewalks in the city of Eureka were made of 2-inch redwood planks. In the downtown area the sidewalks were 12-feet wide with planks running crosswise. In the outlying districts the walks consisted of two or three, 2x12 planks running lengthwise. The last remaining plank sidewalk in Eureka was torn up this year but one can see what they looked like by referring to old photos of the downtown area.

Some of the early cement contractors were: Worswick and Paine, Englehart Construction Co., Mercer Fraser Co., E. Morganti, Eureka Paving Co., Al Hill, Winston Olander, Jim Hubbard, Herb Langdon and Al Pearl. The later contractors included Walter Chase and O.E. Lombardi.

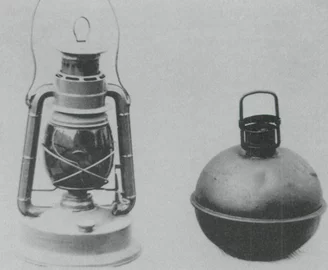

If a pile of gravel was to be left out on the street overnight, red coal oil lanterns would be lit and put on top to keep someone from running into it. Once in a while someone would steal these lanterns or break them. So, in later days, they were replaced with coal oil torches. The torches looked a little like bombs. They were black and measured 10 inches in diameter. These were not stolen as often as no one had use for them. Both lanterns and torches had to be refilled with kerosene and lit every night.

In the 1920s Portland cement came in burlap bags shaped like gunnysacks; the bags were later made of heavy cloth. When empty, these bags were hauled back to the dealer who gave credit for them. The dealers had large cylinder screens about 6 feet in diameter which revolved. The empty sacks were put in this screen and revolved for 10 minutes, shaking the last remaining cement out. This loose cement was scooped up and sold by the pound to the public. The cleaned bags were tied in bundles, tagged, then shipped back to the cement factory for credit. One such sack screen was located next to the Nelson Steamship Company Warehouse at the foot of C Street (cement often came in on Nelson ships). I recall handling many of these cement sacks at this place.

In the late 1930s cement came out in paper sacks. A sack of Portland cement contains 1 cubic foot and weighs 94 pounds. Those old cloth sacks of cement were very hard to handle, and I recall having had very sore fingers from this work. You couldn’t wear gloves and the abrasive sack would wear the skin off our fingers.

My first contact with concrete mixing occurred while attending Eureka High School during its woodworking class. J.E. Doren, the teacher, required the students who had taken his class for two years to mix concrete and pour it into forms for concrete posts. Those students who worked at this had their initials and the date they were to graduate impressed into a post. After the posts were removed, the forms were cleaned and oiled, ready for another batch. These posts were about 7 feet long and 5 inches square with beveled corners. They were installed all around the old high school grounds. Mine was installed right on the J Street side, with “G N N 28” on it.

In 1927 I was fortunate enough to be hired as apprentice carpenter by Halsby and Lax Contractors to work on the building of a large water tank located on the northeast corner of Harris and E streets in Eureka. Part of my job was to help with the concrete pouring. Al Hill, who held the contract to pour the concrete, had an old concrete mixer consisting of a wooden barrel on a four, iron- wheel trailer. This barrel was turned by a one-cylinder gasoline engine with a chain drive which was a lot better than mixing by hand. The wheelbarrows also had iron wheels, which were tricky and hard to handle. One had better not run off the plank with them or one would lose the load of concrete.

I remember back to 1928 when John Halsby, contractor, was awarded the job to install a cyclone fence around the deer and elk pen at the Sequoia Park — the first cyclone fence ever installed in this area. The iron posts had to be set in concrete and a low concrete base had to be poured all the way around this pen, several hundred feet long. Another young man, Allan Moe, and myself were apprentice carpenters working for Halsby at this time. Halsby had us build a mortar box on a sled about 10 feet long, with a chain fastened to the front. Halsby then hired a team of horses to pull this sled around to the gravel piles by hand in this sled, then it was pulled around the fence forms and shoveled in. Part of this fence still remains as a monument to our hard work.

During 1926 the Englehart Paving Company had a contract to pave Seventh Street and Henderson Street with concrete, two of the finest street pavement projects in Eureka to this day. Englehart had a concrete mixer plant at the foot of K Street which processed the gravel and cement delivered by railroad. The company had several Model T Ford dump trucks which hauled about one yard of concrete each to the job. The box on the back had to be cranked up by hand in order to dump the concrete. The mixture was then spread by hand and screeded off with a long plank tilted on its edge and with plow handles on each end. The concrete was then tamped to form a good surface. These streets are still there today though covered with asphalt.

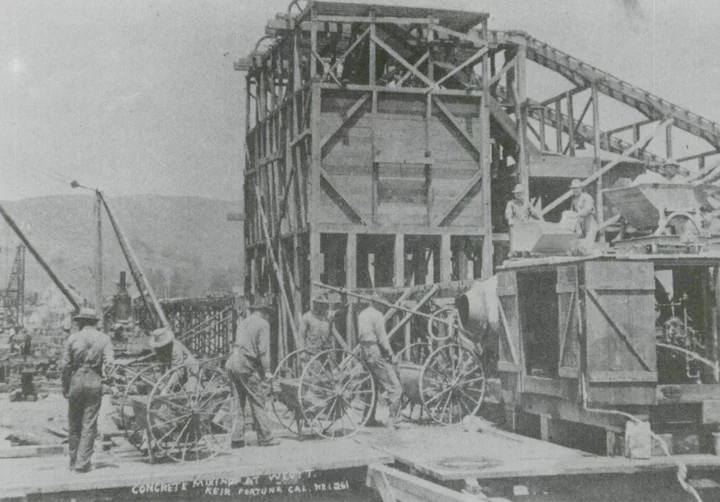

Dozens of men worked long hours at pouring the concrete used to construct Fernbridge. Note the large, iron wheel carts used in the process.

One of the early, very large jobs of concrete pouring was the Fernbridge in 1910. A concrete batching plant was first set up, complete with large concrete mixer. The concrete was wheeled out on the bridge by men pushing iron, two-wheel concrete carts. Thousands of yards of concrete were poured and still stand today.

Many concrete buildings in Eureka were built pouring concrete with the use of old concrete mixers and wheelbarrows. Building projects included the Eureka Auditorium, the Veterans Memorial Building, the Montgomery Ward Building (which is now the U.S. Bank on Fourth and F streets) and many other smaller buildings.

In the late 1930s concrete mixer trucks came into use; this revolutionized concrete mixing and pouring, and made the job much easier. Gasoline-powered concrete buggies, power trowels and electric vibrators also came onto the concrete scene.

Today concrete is hauled to the job sites by giant mixer trucks hauling 12 yards or more of ready-mixed concrete. Mixed according to specifications, it is pumped by concrete pumps into forms and floors,vibrated with electric or gasoline powered machines, then finished with power troweling machines. Concrete work has become much easier and faster. I personally don’t think the concrete is any better, but a lot less sweat goes into it.

###

The story above was originally printed in the March-April 1993 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE