Agricultural land in the fertile Eel River Valley gets irrigated during dry months via wells that draw from the alluvial aquifer. A lawsuit argues that this extraction negatively impacts fish habitat in the nearby river. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

PREVIOUSLY

- Friends of the Eel River Sues County for Failure to Protect Public Trust by Regulating Groundwater Extractions in Lower Eel

- County Staff Present Groundwater Sustainability Plan for Eel River Valley

###

In extremely dry years like 2014, when the water level in the Lower Eel River gets so low that in some spots it goes completely underground, does Humboldt County have a responsibility to curtail groundwater pumping in the basin?

A lawsuit brought by Friends of the Eel River (FOER) says it absolutely does. Appearing in Humboldt County Superior Court on Friday, the environmental nonprofit’s attorney, Michael Lozeau, argued that the county has failed to adequately consider, much less protect, the public trust resources in the Eel River during the late summer and early fall. In that time of year, farmers irrigate their crops with water pumped out of the alluvial aquifer, further degrading conditions in the nearby Eel, which serves as critical habitat for Chinook salmon, coho salmon and steelhead.

“The county’s duties under the public trust [doctrine] don’t take the summer off,” Lozeau said before Judge Kelly Neel. “It applies all year round.”

FOER’s suit, first filed in 2022, is built off of a 2018 California appellate court decision in a case up in Siskiyou County. The Environmental Law Foundation (ELF) had sued the California State Water Resources Control Board over the same type of dynamic — the effects of pumping groundwater that feeds into a navigable river, in this case the Scott River. The judge’s ruling in favor of the plaintiffs marked the first time that the public trust doctrine had been extended to include groundwater.

The public trust doctrine, which has roots in ancient Roman law, is a legal principle holding that certain cultural and natural resources are preserved for public use. Here in California, the umbrella of public trust protections has been expanding. While the doctrine has long protected California’s coastal waters and navigable rivers, a landmark 1983 California Supreme Court ruling extended public trust protections to the tributary creeks that feed Mono Lake. It also established that citizen groups like FOER have standing to file suit under the public trust doctrine.

Cut to the 2018 Siskiyou County ruling, which opened the door to more public trust lawsuits concerning groundwater. Just last year, for example, a trial court found that Sonoma County’s groundwater well ordinance violated the public trust by allowing excessive pumping to dry up streams, damaging vital fish habitat. There have been similar public trust cases in Contra Costa, Napa and Kern counties.

Scott Greacen, FOER’s conservation director, told the Outpost that such lawsuits are necessary due to the fundamental inadequacy of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), a 2014 law that established a “framework” aimed at protecting the state’s groundwater resources long term.

“SGMA was much heralded as, ‘California is finally regulating groundwater,’” Greacen said. “It doesn’t.”

Instead, he contends, the law merely requires certain local jurisdictions — those with designated critical-, high- and medium-priority basins — to “put up a decent show” of regulating groundwater.

The Eel River Valley has been classified as a medium-priority basin, much to the annoyance of many locals, including dairy farmers who sometimes consider the water beneath their land part of their own property, and Humboldt County First District Supervisor Rex Bohn, who argued that the designation was unjustified and the extra regulations unnecessary.

Nevertheless, the Department of Water Resources upheld its designation for the Eel River Valley as medium-priority, which forced Humboldt County to develop a Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP) for the basin.

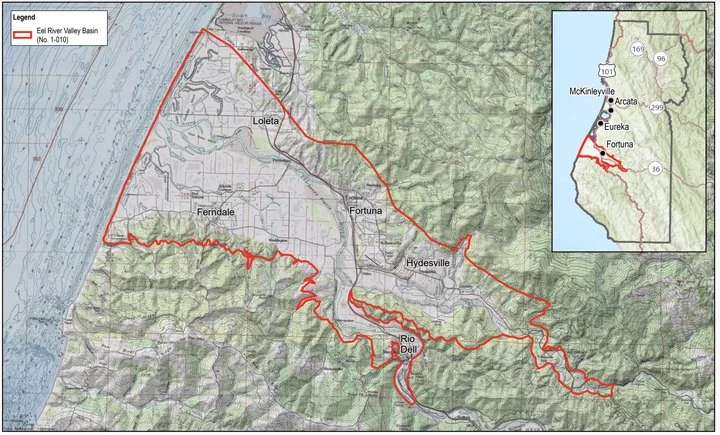

Map of the Eel River Groundwater Basin. | Image via County of Humboldt.

###

Greacen, during our interview, unleashed a bit of sarcasm about the resulting document.

“Shockingly,” he said, “that plan found that there are no ‘undesirable effects’” of groundwater pumping.

While the county’s Eel River Valley GSP acknowledges a link between groundwater pumping and surface flows along that stretch of river, FOER’s lawsuit alleges that the modeling on which the plan was based only evaluated groundwater impacts when river flows were at 130 cubic feet per second (cfs) or higher, thus failing to consider impacts during lower summer flows when salmon are holding in pools waiting for rain.

In a phone interview on Monday, FOER Executive Director Alicia Hamann said it’s not uncommon for flows in the Lower Eel to fall below 130 cfs by the end of summer, creating dangerously stressful conditions for fish. In 2015, for example, pre-spawning salmon collected from pools in the Lower Eel River during the late summer and early fall were found to have damaged eyes, brains and spinal cords.

FOER’s brief cites analysis from fisheries biologist Dr. Gabriel Rossi, who concludes that the “obvious inhospitable environmental conditions” in the Eel that year, including anemic flow, warm temperatures, algal accretion and low dissolved oxygen, can reasonably be tied to reductions in surface flow caused by nearby groundwater pumping during such dry times.

“And we know we will have unpredictable and more dry times in the future,” Hamann said.

In March of 2023, six months after FOER filed its lawsuit, the County Division of Environmental Health began doing public trust analyses for new or replacement well permits. But FOER’s lawsuit argues that because these analyses are based on a flawed GSP, it fails to consider impacts to the Lower Eel during low-flow conditions.

FOER’s lawsuit doesn’t request a specific remedy from the county, a fact that Judge Neel remarked upon in court Friday.

“What exactly is your client asking the court to do?” she asked. She noted that the county can’t exactly account for “what are likely the many illegal takings of water for unpermitted [cannabis] grow sites,” so what does FOER want?

Lozeau, the attorney, said they’re requesting an order compelling the county to comply with its public trust duty “to consider the adverse effects of groundwater pumping on this stretch of the Lower Eel [during] this period of time … in particular during critical dry years.”

Hamann put it another way during our phone interview: “We’re asking for the county to do something,” she said. “We just want more than nothing, which is what they’ve been doing.”

Then, striking a note of confidence, she added, “After we win this case I will happily go to the county with lots of ideas for solutions they can enact.”

The lower mainstem Eel disconnected in August 2014, as seen in this aerial photograph by David Sopjes.

The county’s defense

In court on Friday, the county was represented by Christian Marsh, an environmental and land use attorney with the San Francisco firm of Stoel Rives, LLP. Joining him at the defense table was Humboldt County Deputy Director of Environmental Services Hank Seemann, with members of county counsel sitting in the gallery behind them.

In response to Lozeau’s opening remarks, Marsh said he, his clients and their experts “disagree vehemently” with the conclusion that groundwater pumping — as opposed to severe droughts, surface water diversions or other hydrologic factors — is having a substantial influence on water flows in the Eel.

“FOER’s assertion is speculative and confuses correlation with causation,” the county’s opposition brief says.

That document also argues that the county has adequately considered the public trust doctrine through its development and adoption of a GSP, its individual analyses for well permits and its use of scientific modeling to assess impacts on salmon migration. Salmonids adapt to changing circumstances, Marsh said before Judge Neel, noting that when the river disconnects as it did in 2014, fish simply hold off on their upstream migration until conditions are suitable.

One of the county’s own expert biologists, Dr. Charles Hanson, found that salmon originating in the Eel River “have evolved a synchrony” between adult upstream migration and the environmental cues associated with autumnal rainfall.

The county further argues that recent severe droughts may not even have had significant negative impacts on Chinook salmon. Its court brief notes that the number of Chinook that “successfully migrated upstream through the Van Arsdale Fish Station in 2014, 2015, and 2021 did not appear to be statistically lower than in wetter years, likely due to strong fall rainfall events.”

Besides which, Marsh argued, there has been no “triggering event” to sue over — no specific action, such as the issuing of a well permit, that violated the public trust doctrine.

Furthermore, his brief argues, most of the wells that draw from the valley’s alluvial aquifer were installed decades ago, which means FOER is not entitled to any relief from the court.

The brief also notes the county’s active role in working to decommission Pacific Gas & Electric’s Potter Valley Project, a hydroelectric facility with dams and tunnels that divert water from the Eel to the Russian River watershed. PG&E recently filed its application to surrender its license and decommission the facility, which will “restore a free-flowing Eel River and re-establish fish passage to upstream habitats,” the county’s brief notes.

Hamann said that while that’s true — and dam removal has been her organization’s top goal since its inception — she and FOER’s expert analysts don’t expect it to result in significant changes to flow in the Eel.

“Right now they do a pretty good job of mirroring the natural hydrograph,” she said in reference to seasonal water releases. After the dams come down, FOER expects some highs to be higher and some lows lower, which won’t alleviate the inhospitable conditions for salmonids during the dry season.

FOER’s brief notes that Eel River salmon populations are at approximately 5% or less of their historic abundances.

Hamann discredited the county’s defense arguments, noting that its own scientific modeling acknowledges a hydrologic connection between the Lower Eel River and its surrounding alluvial aquifer. She said the county has a “continuous” duty to consider any adverse impacts to the public trust and reiterated that Humboldt County has still not analyzed the impacts of groundwater pumping in the Eel River Valley during the summer months.

Asked for comment, Seemann declined on behalf of the county due to the case’s status awaiting decision.

After listening to both sides plead their cases on Friday, Judge Neel said she will take the matter under submission. She has 90 days in which to issue a ruling.

###

DOCUMENTS

CLICK TO MANAGE