The serpentine soil samples were collected at Eight Dollar Mountain in southern Oregon. | Photo: Matthew Polizzotto

###

The Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains are home to one of the nation’s largest deposits of serpentine, a rare, chromium-rich soil produced by weathered ultramafic rock. While relatively harmless in its benign rock and soil form, new research shows that chromium can turn into a carcinogen during wildfires.

The study, authored by Cal Poly Humboldt soils scientist Chelsea Obeidy, breaks down how chromium can convert into a carcinogen — hexavalent chromium, or chromium-6, a toxic heavy metal dubbed the Erin Brokovich chemical for its role in the landmark water contamination lawsuit — when exposed to extreme heat. That chemical can then leach into groundwater.

The research, published last month in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Science & Technology, calls for a deeper understanding of how wildfire can affect soil contaminants. “In a rapidly changing climate where soil and water resources are increasingly important and where wildfire intensity, extent, and recurrence are increasing, it is essential to understand the landscape controls on soil and water quality,” the study states.

Obeidy was inspired to look deeper into the subject while working on her Ph.D with Matthew Polizzotto, an earth scientist and environmental chemist at the University of Oregon. During her research, she came across a study out of Stanford that found elevated levels of hexavalent chromium in fire-affected soils near Santa Rosa, prompting the question: How do wildfires affect chromium-rich serpentine soils in northern California and southern Oregon?

“There isn’t a lot of research on this topic,” Obeidy told the Outpost. “There’s been some studies that have measured it in river systems after a fire, but overall, there just needs to be more research. … Serpentine soils — even without wildfire — sometimes have elevated concentrations of this carcinogen associated with their groundwater … but we still don’t understand how it’s getting in the groundwater.”

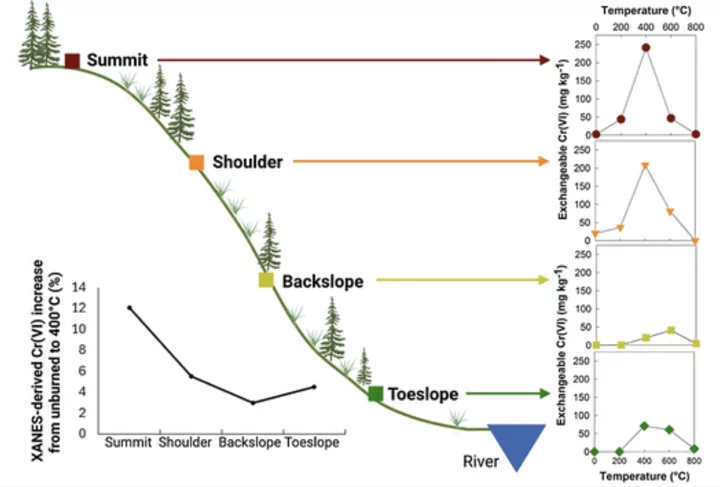

Obeidy and her colleagues made the trek to Eight Dollar Mountain, an expansive botanical range located in the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest in southern Oregon, to collect soil samples at different elevations to capture a range of soil weathering.

“We were really curious about how variations like temperature, burn intensity or landscape position — at the summit, in the middle of a big hillslope and down by the river — impact how chromium-6 varies,” she explained. “We sampled the soils and conducted these little experiments on them to figure out how chromium-6 would be generated at different temperatures.”

Graphic: University of Oregon

By “little experiments,” Obeidy means they torched the soil samples to simulate wildfire intensity. Samples that were taken from the summit and burned at 750ºF produced the highest concentrations of the carcinogen, whereas low-intensity fires generated less.

To recreate the effect of rainwater passing through the soil, they packed burned and unburned samples into plastic columns and pumped them with a synthetic rainwater solution to simulate one year of precipitation.

“We wanted to quantify how long this contamination would last [in the environment],” Obeidy said. “And we found that, yeah, it could last from anywhere from a half a year to two years, and that really was dependent on the temperature and position in the landscape.”

There’s no indication that the carcinogen has had any significant impacts on the environment or regional water supplies as of yet, but “it definitely could,” Obeidy said. “We want to get the word out and for people to be aware, but I don’t want to scare people. … There just needs to be more research on it.”

Ultimately, she hopes agencies like CalFire and the U.S. Forest Service will take this research into account during the post-fire response and clean up to ensure groundwater isn’t being contaminated.

“We should be monitoring for chromium-6 in these post-fire landscapes, just to make sure that people’s drinking water is safe,” she said, adding that well water should be subject to additional testing. “It should definitely be investigated further.”

You can check out the study here.

CLICK TO MANAGE