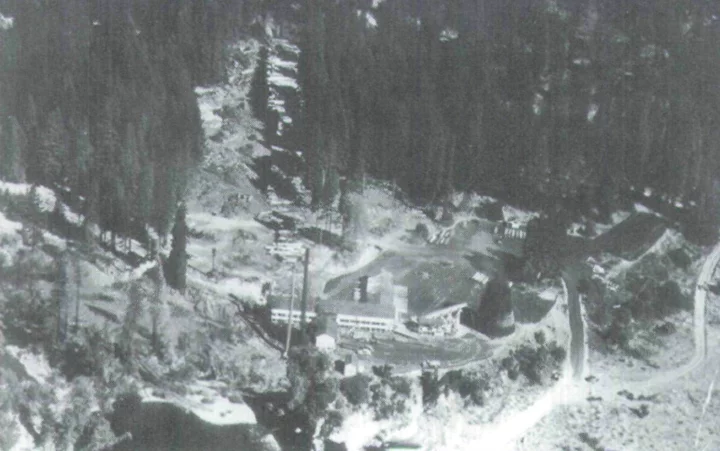

Andersonia in the 1940s, about the time Samuel Anderson, Pap’s oldest surviving son, moved with his three sons to start a new mill.

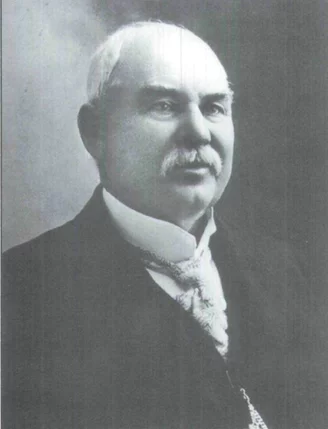

Fortune had smiled on him

for sixty-six years. He had been blessed with a large family of

twelve children, prospered by

the time he was thirty-one years

later in the timber industry, and

moved to California in 1903 to

supervise his latest half-million-dollar land acquisition. He

knew how to organize and

manage; he designed his mill

and its surrounding community

with the latest technology and

most modern conveniences in

mind. But the vision Henry

Neff Anderson had for his

model mill town, Andersonia,

did not anticipate the disaster

that befell him shortly before

opening day, and it certainly did

not include the bad luck that

has plagued his mill throughout this century.

Henry Neff “Pap” Anderson was born on August 2, 1839, in Altoona, Pennsylvania. He was the fourth of at least five children. (Five appear on the census in 1850 and 1860, but other children also appear in later records.)

Pap was reared on a farm in rural Allegheny Township, which his family had owned since the early 1800s, and he lived much of his early life in Altoona. He served in the Civil War along with his older brother Samuel, and later in the Pennsylvania Militia. After the Civil War and while still in his prime, he was self-employed as a contractor and miller in Pennsylvania’s timber industry. With the high prices lumber acquired during the 1860s and 1870s and Pap’s sharp business acumen, he became a “self-made man.” By the time of the 1870 census he had over $14,000 in real estate and personal wealth, married Sara Counsman and fathered five children. One of the businesses he helped found and manage was the Citizen Steam Grist Mill, which he ran until 1874.

When timber became scarce in Pennsylvania and national consumption remained high. Pap set his sights on Michigan’s lumber frontier and in 1878, moved his growing family to Greenville. He built the first sawmill in Basslake, Michigan, with James Louder, and also the Anderson Graffin sawmill in West Troy, which allowed him to substantially increase his family’s wealth over the next twenty years.

Pap soon followed others to yet another timber frontier when the Michigan white pine woods began to diminish. The “tall and uncut” in Grays Harbor, Washington, and a mill up for auction there beckoned. In 1898, Pap and Albert W. Middleton, his son-in-law, successfully bid for the Weatherwax Mill in Aberdeen, which they jointly owned and operated under the name of Anderson & Middleton Lumber Company. The Anderson and Middleton families became “irremovable fixtures” in the Grays Harbor area, and Pap’s wealth continued to increase.

The capital from his companies, along with his business savvy, allowed him to make decisions that later put him in a position with other lumbermen to invest over $500,000 in Andersonia and the surrounding areas of southern Humboldt and northern Mendocino counties.

Andersonia.

Bear Harbor

Some twenty years earlier in Redwood Country, events occurred that eventually would lead Pap to California and, ultimately, to his death. But his was neither the first nor the last tragedy linked to this area. Bear Harbor, situated midway between Eureka and Fort Bragg along the Northern California coast, saw timber development as early as 1882. C. C. Milton began building a wharf there to facilitate the shipping of tanbark and railroad ties. He drowned at nearby Rockport before construction could be completed.

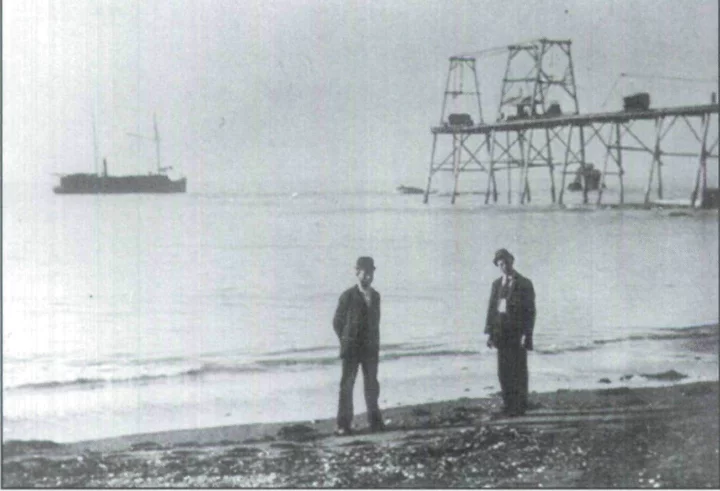

Bear Harbor.

The wharf stood in disuse until 1885 when Dr. W. A. McCormack finished it and added a chute that permitted schooners to load or unload directly from the site.

By the late 1890s, new markets were opening up for American lumber. In a diminished role as controller of exports and determiner of consumption, San Francisco took a backseat to Japan, Australia, South Africa and others, as timber barons along the West Coast sought and found new markets for their produce. The United States saw a dwindling need for its timber with the completion of the transcontinental railroads, and many lumber companies joined forces, forming cooperatives to control prices and production in an oft-futile attempt to stave off bankruptcy. Such was the case when Mr. Weiler and Calvin Stewart bought out McCormack’s business in 1890, and two years later, they, along with a group of Humboldt County men from the Union Lumber and the Eel River Valley Lumber companies, acquired 12,000 acres of timber east of Bear Harbor.

They planned to build a railroad into the interior for logging purposes and ordered a Gypsy (Engine No. One) from the Marschutz and Cantrell Company in San Francisco. On July 26, 1893, the Bear Harbor Lumber Company (BHLC) was formed. By 1896, ten miles of track led from the incline east of Bear Harbor into Moody, where Lew Moody had constructed a hotel and saloon. On September 8, 1896, BHLC incorporated the Bear Harbor and Eel River Railroad (BH&ERR), and in 1898, a Baldwin (Engine No. Two) was ordered and a route was surveyed to run east to the South Fork of the Eel River and then north to Garberville. But misfortune came between success and investors again. In 1899, a tidal wave destroyed the wharf at Bear Harbor and construction by the company came to a halt. Money ran out.

In 1903, Calvin Stewart, Mr. Dodge, and Tom Pollard, seen here with Jay Thomas at the Bear Harbor Chute in 1893, sold the Southern Humboldt Lumber Company to Pap Anderson and several other men.

Pap Steps In

Word soon reached Washington and Pap Anderson that a timber company with a small rail line had gone bankrupt. Pap had previously bought and restored another bankrupt company (the Weatherwax Mill in Aberdeen) and would do so again. To increase the milling capacity of his two mills in Grays Harbor, Pap purchased 10,000 acres of redwood on November 1, 1902, and later annexed an additional 5,000 acres, located in southern Humboldt and northern Mendocino counties along Indian Creek, a tributary between the South Fork of the Eel River and Bear Harbor in Northern California. Anderson, Middleton and the McPherson brothers, also of Grays Harbor, then joined with Tom Pollard, Calvin Stewart, and Mr. Dodge to form the Southern Humboldt Lumber Company (SHLC) five days later on November 6. Pap was appointed president, Stewart vice president, Pollard secretary, and son-in-law Middleton, as in Michigan and Washington, assumed the role of treasurer. By June of the following year, the SHLC was ready to buy out the Bear Harbor Lumber Company along with the Bear Harbor and Eel River Railroad.

The SHLC intended to log its 15,000 acres and transport the lumber first to Moody and then on to Bear Harbor via an elaborate system of yarding, floating, and portage. The company itself had no plans to mill the lumber. Instead, they commissioned the Pollard Steamship Company of San Francisco to transport the timber from Bear Harbor to Grays Harbor for milling.

But the long-term design was to connect their tracks to the railroad line being built from the Bay Area northwards, which was planned to pass Andersonia along the South Fork of the Eel River and carry the lumber and tanbark to southern mills and tanneries. This was the main reason they built their railroad using standard gauge: the engines and rail had to be the same gauge as the proposed railroad coming from the south. Ultimately, this would lead to the demise, or at least a drastic reduction in use, of the wharf and incline at Bear Harbor.

By mid-1903. Pollard, Dodge, and Stewart allowed Anderson, Middleton and the McPherson brothers to buy them out when Pap announced his plans to build a modern mill at the junction of the South Fork of the Eel River and Indian Creek: Camp 10. Pap wanted to mill his own lumber and build his own town, which he would call Andersonia. Pap Anderson was visionary: shipping timber via steamships and smaller schooners was soon to be a thing of the past as railroad companies offered bonuses and shipping rates too good to pass up. Pap would be prepared with his standard gauge railway and high-grade, clear timber that was much sought after from Humboldt and northern Mendocino counties.

A Mill and a Town

Pap Anderson had his engineers survey the site, and then he designed not only a modern mill, but a modern community resplendent with gardens and orchards for the loggers, mill workers, and their families. He spared no expense. He ordered six state-of-the-art boilers, two Allis-Chalmers band saws, a 116-ton flywheel driven by two 1,100-horsepower twin engines and other innovative sawmill equipment. Almost 200 workers were recruited from Michigan, Grays Harbor, and locally to build the mill, finish the rail line into Andersonia, dam Indian Creek to create a millpond, and log half a billion feet of standing timber in anticipation of start-up.

By late October 1905, everything was coming together. The dam was built and the millpond was stocked to capacity with logs totaling twenty million board feet. More timber was felled to replenish the millpond once milling began. With the tunnel and bridges finished, the Moody to Andersonia portion of the rail line gave the company over seventeen miles of track from Bear Harbor to the new mill.

The shabby tents that had marked Camp 10 were gradually replaced with smart cabins. And Pap had built a large two-story house for his new bride, Miss Cora Patterson.

Tragedy Occurs

Last-minute preparations were made for Dedication Day of what would be a model mill for California and the Pacific Northwest. Pap, in great anticipation, walked his rounds. He was most interested in adjustments the engineers had to make to a support joist in one of the roofs. As a piece of machinery was being moved into place, workers had found the opening too narrow for the apparatus to fit. They were installing a new beam when Pap came in to watch. Humboldt Standard newspaper articles from that time give a sampling of the disaster that befell Henry Neff Anderson.

November 1, 1905: “October 28th. A telephone message was received late this afternoon from Andersonia for Dr. Rossier to come at once to that town as Mr. Anderson had received an injury from a piece of timber falling on him.”

November 10, 1905: “A telephone message was received yesterday morning of the death of H.M. (sic) Anderson, president of the Southern Humboldt Lumber Company at Andersonia, who died from injuries received at his mill October 28th. After the operation on his head, relieving the pressure on the brain, he rallied for a short time, but his age, being a man well advanced in years, was a retard to his recovery, and the call from the Great Beyond came at 7 o’clock, November 7th. Mr. Anderson will be greatly missed from Mendocino County and Andersonia, the town named in his honor. He started life a poor man, but by perseverance and energy he gained a competence and at his death was one of the multimillionaires of the state, making the principal part of his holdings in timber. He owned vast tracts of timber in Michigan and California. He was president of the Southern Humboldt Lumber Co. for a number of years before his death. The large sawmill being built at Andersonia was one of his possessions. Mr. Anderson leaves to mourn his death a wife and several grown children.”

And with those last reported words, the bad luck of Pap’s dream mill was sealed. Litigation followed between his children, who were all from his first marriage, and his young second wife, Cora. The Southern Humboldt Lumber Company lost the right to transact business for the Bear Harbor Lumber Company and Bear Harbor and Eel River Railroad when the franchise tax came due and was not paid during the litigation. Work was all but stopped at Andersonia while needed parts and machinery were delayed from San Francisco and repairs were slowed on the wharf, which had sustained damage during a severe storm in March 1906.

The Big One

A second disaster struck the mill shortly after Pap’s death: The earthquake of April 18, 1906. Shortly before the earthquake, a potential buyer, Mr. Trumbull, inquired about purchasing the mill for his son. He made an offer that was accepted by both parties in the estate litigation, but on the trip to San Francisco to finalize the deed transfer, the earthquake changed Mr. Trumbull’s mind about California, and he backed out of the deal.

The physical damage caused by the earthquake also took a heavy toll at Andersonia and Moody. Work, which had been excruciatingly slow due to downtime spent waiting for parts, was slowed even further by repairs that had to be made to earthquake-damaged buildings. Restoration to the mill only ran into the hundreds of dollars, but when estimates were made to mend damage done to the millpond, work halted. Thousands of additional dollars would be needed to fix the dam, and money was becoming scarce. Litigation, coupled with earthquake damage, crippled any chance for the mill to operate.

Not only did the earthquake ruin the rail line, mill, and the dam at the millpond, it burned the South Fork survey plans that the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway had commissioned. There were two proposed routes from the Bay Area to Northern California: both reached Longvale in Mendocino County, but then took divergent routes north. Pap and his associates had hoped the company would choose the more accessible and resource-filled route along the South Fork of the Eel River — directly past Andersonia. The fire resulting from the earthquake destroyed the plans that showed the South Fork route, and the company did not commission its replacement. Instead, they chose the route whose survey plans survived, along the main branch of the Eel River, much farther inland.

A Second Chance?

Without milling a single piece of lumber, the SHLC could not afford to rebuild the wharf or to lay track east to the Eel River and the main rail line. This final punch closed Andersonia, forcing loggers, carpenters, machinists, and their families to move away.

A few years later, another buyer, Mr. Hicks, made a bid for Andersonia. He believed the mill could be made operational with some retrofitting and updating. The first cut of timber still lay in the millpond and on the forest floor, and almost all the equipment remained on site. The prospective buyer made his way to San Francisco to finalize the deed transfer. Once again, bad luck kept Andersonia from fulfilling its promise to Pap. While in San Francisco, Mr. Hicks committed suicide in his hotel room.

For a time, nothing happened. A few pieces of equipment were sold to other mills seeking to upgrade their machinery. Then the winter of 1925-26 brought heavy rains. The dam, weakened by the 1906 earthquake, finally gave way, and the timber that had spent twenty years in the millpond stampeded down the South Fork of the Eel. (Some men, hoping to salvage good timber, tried to net the logs as they stormed their way to the ocean. Their nets were ripped to shreds as the logs shot past. Some of the timber was salvaged from the river shores as it hung up in natural snags and more was salvaged on the ocean shore, but most was swept out to sea.) That same season, with its torrential rains, saw the washout of some of the tracks, which stranded the two engines stored in the enginehouse in Moody. But even with its future looking so forlorn, Andersonia still attracted dreamers.

And they, too, were Andersons.

In 1940, Samuel Miles Anderson Sr., Pap’s oldest surviving son, brought his three sons and their families from Aberdeen, Washington. The estate had filed a claim to recover the property, paid the back taxes for years past, and planned a smaller version of the first mill to be built. Timber remained from the original cut that had been left lying on the forest floor since 1905. Estimates placed the salvageable timber at about 400,000 board feet. The Andersons established the Indian Creek Lumber Company, and the three brothers, Reginald, Harold, and Sam Jr., all worked in some capacity at the new mill. Reginald supervised the entire operation, Harold managed the woods, and Sam Jr. took charge of maintenance. At long last, Pap’s dream seemed close to coming true. But Andersonia would not remain successful for long. Descendants of the men who sold their holdings to Pap in 1903 filed a lawsuit to regain control of the mill, and that, coupled with nationwide timber industry problems resulting from World War II, led to a shutdown in the late 1940s. Once again, the mill stood silent.

In 1950, Thomas Dimmick reached an agreement with the Anderson family. He would run the mill and log the surrounding area for the Andersons. Under Dimmick’s guidance and with outside supervision from the Anderson family, the mill operated until 1972, when the second-growth timber had been logged and milled. But timber is not the only treasure left at Andersonia.

What Remains

The remote location, destruction of the tracks from the earthquake in 1906, the floods of 1925-26, and the passage of time had aided in the partial preservation of the two steam engines. The Baldwin (Engine No. Two), which had remained at the mill site’s storage building, was being renovated surreptitiously when vandals were discovered, and some of the engine was recovered. However, the combination of brass smelting from World War I and loss due to the vandals meant too many pieces were lost irrevocably for Engine No. 2 to be restored. She now “piecefully” rests in the Northern Counties Logging Interpretive Association’s (NCLIA) storage facility.

The Gypsy, however, has made a miraculous comeback. In 1977, Pap’s great-grandson, R. Grant Anderson Jr. and Rogan Coombs, along with an entourage of other locomotive enthusiasts, rescued the Gypsy. After spending nearly fifty-two years in the enginehouse outside of Moody, she was removed piece by piece from the enginehouse to be restored. Later, the Anderson family donated the engine to the State of California, and it came to rest at Fort Humboldt’s logging museum in Eureka. Since being restored by the NCLIA to near-new condition, she has the proud distinction of being the only operating Gypsy in the world.

Time has not been kind to Andersonia. Other than the large teepee burner rusting near the river, there are no longer signs that two mills once stood above the banks. But buildings spanning ninety years still rest on the site. A newer office building erected by Sam Jr. remains tenaciously upright in tribute to his hopes for continuing the family dream. Sam followed in his grandfather’s stylish steps when he built the office: no fewer than eight sixteen-by-sixteen-inch beams grace the porch. Across Indian Creek, Pap’s two-story bridal gift to Cora still stands, though even a slight tremor could prove fatal.

Time has given the forest a chance to regrow. Now Andersonia waits quietly, even expectantly, amid an ocean of sorrel washing upon banks of Scotch broom. Mint scents the air above little heads of mushrooms pecking out in the fields. Primitive horsetails stand like sentinels watching four blue spruce scream their planted presence around the old office. And a lonely old apple tree sits overgrown and blooming, seemingly oblivious to its striking attendance against its backdrop of timber, mature and ready for harvest. The surroundings seem a surreal backdrop to one of the most tragic stories told of lumber barons in the 19th century. Many men made fortunes along the same path; Pennsylvania, Michigan, and along the Pacific Coast, including Asa Simpson, founder of one of the more famous lumber companies.

Pap’s story is tragic in its promise unfulfilled: the mill was without its great leader for the all-time peak of lumber consumption in this country in 1907. How great would our memory be of Henry Neff Anderson if a piece of timber hadn’t taken out this timber baron? Today, hardly anyone outside his family knows of Henry Neff “Pap” Anderson. The memories are only slightly more vivid in Grays Harbor, Washington, where he made his most lasting economic and social impact on the community. In southern Humboldt and northern Mendocino counties, there will always and only be the legacy of being the place where he met an untimely death and left deserted the most promising of Pacific Coast mills.

For his family, there is a permanent legacy with some of Pap’s land now in the King Range and Sinkyone Wilderness. But, with the recent passing of one of the heirs of the remaining Andersonia land, once again, a question hangs over the area. Will the mill and timber finally be sold out of the family? Who, if anyone, will become heir to Pap’s dream?

###

About the Author: Lorraine Michaels is a 1999 graduate of Humboldt State University, majoring in social science education. The story printed here is excerpted from her third-place entry in the Charles R. Barnum Humboldt History Competition.

###

The story above was originally printed in the Winter 1999 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE