State Route 96 is the only paved road into and out of the remote rural community of Weitchpec. | Photos by Ryan Burns

On the back deck of the Yurok Tribe’s Weitchpec Office, flames jump through a metal grate to lick the sizzling burger patties being grilled for tonight’s community meeting. Fixings have been arranged on a portable table on the grass below — buns, condiments and foil-covered bowls of veggies, potato salad and baked beans. At the far end of the table a bowl of fresh-cut strawberries sits beside plastic-wrapped shortcake rounds and three red-capped cans of whipped cream.

The tribal office also serves as a community center and sits on a verdant bluff above the confluence of the Klamath and Trinity rivers. It’s a warm, overcast Friday evening in Weitchpec, a community of about 150 people in one of the most remote regions of the country. Tonight, a couple dozen residents have gathered at this barbecue to talk about suicide.

It’s been more than four months since the Yurok Tribe declared a state of emergency in response to the self-inflicted deaths of seven tribe members over an 18-month period. The victims were all young, ranging in age from 16 to 32. And while the Yurok Tribe is California’s largest, with more than 5,000 members and a reservation covering nearly 56,000 acres, the victims were all from this particular tiny and isolated rural community.

The only paved road into and out of Weitchpec is State Route 96, a two-lane roadway that winds along the Klamath and Trinity rivers through the Karuk, Yurok and Hoopa tribal reservations.

From this road you’d never know people live in the densely forested hills if not for the tribal office on the river’s north bank and, across the narrow bridge spanning the river, a small church and a convenience store with two old gas pumps out front.

Flyers posted on bulletin boards in front of the store reveal a lot about local life. There are workshops for animal tracking, community gardening and the Yurok language (which has made a remarkable comeback from near-extinction). There are also flyers advertising drug treatment groups and a syringe exchange. A hand-written flyer demands the return of Ted’s stolen gas can and LeRoy’s bike. Another reads, “NO MORE HEROIN METH/PILLS.”

Tonight’s suicide prevention meeting has a flyer, too.

In a community where the nearest grocery store is an hour away (assuming you have access to a car), and where many homes lack internet, cell service and even electricity, self-reliance is key to survival — sometimes literally. (It can take two hours or more for an ambulance to get injured locals to the nearest hospital.)

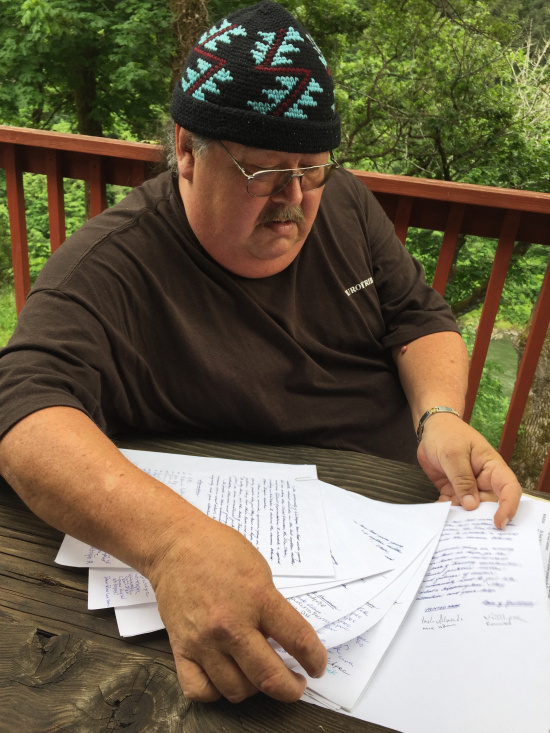

Daniel French

That’s why, after the recent rash of suicides in the area, Daniel French decided to take matters into his own hands. Sitting at a wooden picnic table next to the barbecue grill, French, a large, soft-spoken man wearing a crocheted cap with a traditional Yurok pattern, has lived in Weitchpec his whole life, just like his mother and grandmother before him. And he’s gravely worried about the younger generations.

“My son was one of the people who committed suicide,” he says quietly, eyes cast downward. His son was Damien French, a father of three girls who was 32 when he took his own life. In an unrelated tragedy shortly thereafter, Daniel French’s 18-year-old grandson, a firefighter, drowned in the Trinity River.

“And then my other cousin up here committed suicide,” French continues. “Two brothers committed suicide along with [one brother’s] girlfriend.”

Almost everyone you talk to in Weitchpec has stories like this, about brothers, cousins, nephews or sons who have killed themselves. “Somebody needed to do something,” French says.

He rifles through some paperwork and pulls out a stack held together with a paper clip.

“There’s roughly 250 people in town here,” he says, referring to the larger upriver area of the Yurok Reservation. “And after I wrote that up [in December] I got 215 signatures in three days.”

The front page of the packet is a handwritten statement in French’s elegant blue cursive. It mentions the seven recent deaths and calls on tribal leaders to address the issue:

There is a suicide epidemic going on among young people who feel they have no hope for the future. They love their home and most want to stay here, but the lack of training opportunities, jobs or even recreational facilities invites unhealthy behaviors and feelings of despair.

The people in this community need to feel like someone cares about what’s happening here. They urgently need your attention and your help.

On December 28, the Yurok Tribal Council issued an emergency declaration, describing the situation as a suicide crisis and calling on “all federal, state, local, and tribal emergency management agencies” to coordinate an immediate response. The declaration was sent to numerous agencies and government officials including California Governor Jerry Brown and President Barack Obama.

In January the tribe sent out a press release describing the scope of the problem. It explained, in part, that most of the Yurok Tribe’s therapeutic resources are based at the tribal headquarters in the small town of Klamath, located at the river mouth, on the other end of the reservation. “The only paved road connecting the east and west sides of the rural reservation was washed away in the 1960s and the state highway was never replaced,” the release explains. “Driving from one side of the reservation to the other takes about two hours, including a long stint on a dirt road that is sometimes covered in snow.”

The tribe’s then-chairman, James Dunlap, said, “By far, the Tribe’s need for healing resources outweighs our current capacity.”

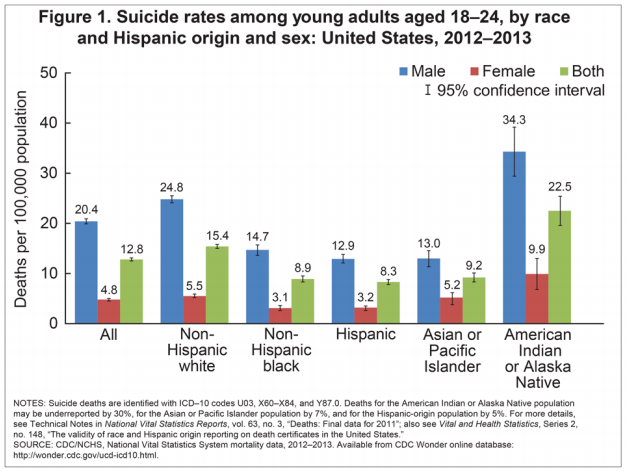

The grim situation in the Yurok Tribe is not unique. Suicide among Native American youth has reached crisis levels nationwide, according to a recent report from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. In 2012-2013, Native American men age 18-24 were more likely to kill themselves than any other ethnicity in that age group (see chart below). And that’s without accounting for the fact that suicides among Native Americans generally are underreported by about 30 percent, the result of coroners writing the wrong ethnicity on death certificates.

But in Weitchpec, the crisis is especially acute. “Among the adolescents and young men living in the Weitchpec area, the [suicide] rate is hundreds of times higher than that of other American Indians/Alaskan Natives,” the tribe declared earlier this year.

The factors contributing to these statistics are numerous and complex. Yurok Tribe members have identified such influences as geographic isolation, substance abuse, scarce job opportunities and the general lack of positive activities for young people. They also cite the historic and ongoing trauma inflicted by massacres, forced relocation, broken promises and the disruption of their traditional ways of life.

Meanwhile, roughly 90 percent of people who commit suicide suffer from mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and Native Americans’ access to mental health resources is extremely limited, especially in rural areas such as Weitchpec.

More broadly, health care spending is anemic throughout Indian country. While national per capital health care spending averages $9,255 annually, Indian Health Services (or IHS, the primary health care provider to Native Americans) spends only about $3,000 per person per year.

IHS responded to the Yurok Tribe’s “State of Emergency” declaration, however, supplying the tribe with much-needed funding to improve social services and bringing in a full-time behavioral health worker to be stationed in Weitchpec. The tribe is also collaborating with United Indian Health Services, the California Rural Indian Health Board and Humboldt County’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) on a variety of initiatives, including the establishment of a new modular building and increased services such as suicide prevention trainings, individual counseling, parenting classes, a peer-advocacy program and increased clinician staffing for the upriver community.

The county has received funding from the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services to provide mental health treatment to tribal children who have been victims of crime, and revenues from the county’s Measure Z tax initiative will go toward hiring clinicians, alcohol and drug counselors and case managers who will be based in the upriver region.

The outside help is welcome, but at the community meeting in Weitchpec the two dozen residents are focused on what they can do themselves, as a community, to prevent more deaths. Gathered in metal-framed chairs on the lush hillside, plates of barbecue in hand, they launch into a group discussion with the familiarity of old friends.

At the suicide prevention community meeting in Weitchpec. A reporter and photographer from the Los Angeles Times were in attendance.

The meeting is being led by Allyson McCovey, a tribal programs manager, and Rose Sylvia, the tribe’s human resources director. “We don’t have our whiteboard tonight, so I’ll just tell you the agenda,” McCovey begins. This is just the latest in a series of suicide prevention meetings, and it won’t be the last. The tribe has also organized a suicide awareness walk, trainings for first responders and a series of Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Trainings (ASIST) for tribal members.

McCovey wants suggestions for how to increase awareness about such activities. Almost anywhere else in the country people would likely turn to Facebook or email for community-wide organizing, and some of that happens here, too. But with so many locals lacking reliable internet, those methods only go so far in Weitchpec. In a recent community survey, 70 percent of residents said they learn about activities through word of mouth.

“Someone had mentioned putting bulletin boards by all the mailboxes that are down the river,” French chimes in. “Everybody goes to their mailboxes.”

Sylvia mentions another proposal: offering punch cards to locals and awarding punches each time they attend a training or other related event. The first person to come in with a fully punched card could be rewarded with a big-ticket prize, Sylvia says. She asks for prize suggestions and people start shouting out ideas: a compound bow, a big-screen TV, a generator, gift cards for food.

“What about free internet for a year from the Tribe?” one woman asks.

“That’s an awesome idea. It is!” another woman replies excitedly. Then, in a bemused tone she adds, “Yeah, but it doesn’t apply to me. I’m around the turn,” meaning she and her family live outside the region’s wireless internet range.

Later in the meeting, Sylvia talks about the ASIST training, how difficult it was to experience and how important it is to get law enforcement, firefighters and other first responders to take it. Two of the recent suicides were Sylvia’s great-nephews. The younger one, Derek, was just 16 when he shot himself. His girlfriend was in the room at the time, and immediately afterward she grabbed the gun and killed herself.

Sylvia, clearly still distraught months later, suspects her great-nephew was being rash and impulsive. “When you’re young like that you don’t have much life experience, so I just think that in a confused state he saw that as the answer,” she said.

Derek’s 18-year-old brother Donald, who witnessed his brother’s death, killed himself a few months later. The boys’ mother had died from cancer shortly after Derek, and the two deaths hit Donald hard. “I think Donald went into a post-traumatic state,” Sylvia said. “He started drinking excessively, driving too fast, stuff like that. I just think he was in this terrible place of loss.”

The boys’ surviving family members, including siblings, half-siblings and step-siblings, are still reeling from the losses. Trauma permeates the whole community, and Sylvia attributes it in part to historic oppression. She mentions a recent study involving Holocaust survivors that suggests intense psychological trauma can actually change a person’s DNA, thereby affecting future generations by making them more susceptible to stress and anxiety disorders.

At the meeting, Sylvia tells the gathered crowd that a particular challenge in the ASIST training was a role-playing activity that simulates talking with a suicidal loved one.

“And I couldn’t do it,” she says, her voice tight. “I got stuck.” But the training opened her eyes. She realized that she’d taken the wrong approach with people who have threatened suicide. Now she hopes to get at least one person from every household — up and down the river — to take the training. “Because it could make that difference,” she says. “We really are going to have to learn how to rely upon each other.”

Alice Chenault.

The training also had a big impact on Alice Chenault, a lifelong Weitchpec resident whose 30-year-old son J.J. killed himself late last year. She described him as a sensitive young man and recounted a story about taking him to Eureka when he was 15. He’d held a door open for a woman, who complimented Chenault on her respectful son.

But J.J. eventually got involved with drugs — meth and probably heroin. He’d been in and out of rehab, and despite earning his Class A truck driver’s license at College of the Redwoods, he’d had trouble finding a job. The nearest truck driving jobs were in Hoopa, 12 miles south, and since J.J. didn’t own a car he’d have to hitchhike to get that far.

Chenault said living in Weitchpec is especially hard on young men. “Because there’s nothing here. I mean, we have this building [the community center], and we have the store. And the drugs.” She shook her head in disgust. “There’s more drug dealers around here than you can shake a stick at.”

Most of them come from outside the reservation, locals say. Historically these outsiders came to grow and sell marijuana, but the tribe has adopted a zero-tolerance policy, banning marijuana operations altogether and calling on local, state and federal law enforcement to help eradicate illicit grows.

Most tribe members support this policy, but French said there have been some unintended consequences. Before the ban, he said, “All the young people would grow a little pot, and they’d have a little money at the end of the year.” Not anymore.

“When you take something away from them like that, you need to give them something back, as in a job or some sort of infrastructure for them to replace those things,” French said. “As the town gets weaker and weaker the people really feel it. It sets in a hopelessness to ’em, you know? What do you do now? You’re just gonna have to leave, I guess, go find some other way. How are you gonna raise a family in a situation like this? How you gonna afford that?”

Chenault blames her son’s death on harder drugs, and the hopelessness and despair they engender. She and others in the tribe are calling for increased law enforcement presence in the area, though, once again, the geographic isolation makes that challenging.

There are also financial and bureaucratic barriers to effective law enforcement here. In 1953 the federal government passed Public Law 280, which, in certain states including California, allowed for the transfer of law enforcement authority on tribal lands from the feds (usually in the form of the Bureau of Indian Affairs) to state agencies and county sheriffs.

This controversial law made the already complex jurisdiction issues on tribal lands even more complicated. Tribes in Public Law 280 states argue that this shifting of authority has had a variety of negative impacts on tribes, making it harder for tribes to develop their own criminal justice systems, reducing overall funding for law enforcement and creating gaps in legal authority.

In 2012 the Yurok Tribe itself argued, “This system has failed Yurok people … . Public Law 280 limits tribal jurisdiction over non-tribal members, making it easier for non-natives to get away with crimes and exploit natural resources on the reservation.”

Yurok Tribal Chairman Thomas O’Rourke is also no fan of Public Law 280, While the Yurok Tribe has its own police force, with some officers cross-deputized by the BIA and the Del Norte and Humboldt County Sheriff’s Offices, it receives no funding through Public Law 280 to support law enforcement.

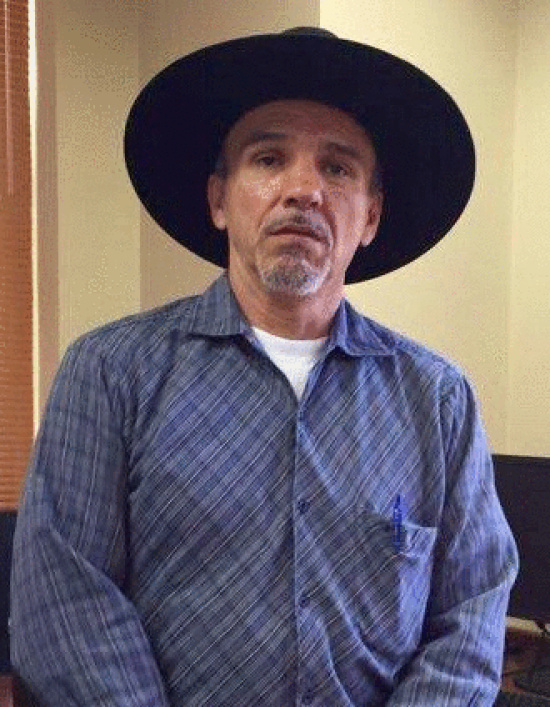

Yurok Tribal Chairman Thomas P. O’Rourke.

This, O’Rourke says, is just another example in a long history of betrayals by what he calls Europeans — the white people who first came here some 250 years ago.

Slight and contemplative, O’Rourke almost always wears his trademark black cowboy hat with the flat brim, and he tends to speak in long paragraphs, patiently approaching the point through history and analogies.

Asked what caused the recent suicide epidemic, for example, O’Rourke goes all the way back to the dawn of time.

“We say we’ve always been here, that we didn’t come across the Bering Straight like they say we did.” He was sitting behind his desk at the Yurok Tribal Headquarters in Klamath, and despite having a meeting in less than an hour he took his time with every answer. “Our stories go all the way back to the time of darkness, when there was only spirit without form here,” he said.

For thousands upon thousands of years Yurok people lived in harmony with the land, never seeing any white people. “And then when they did see ’em, they [the white people] were here with destruction,” he said. “Here to conquer.”

O’Rourke recounts some of the atrocities — the forced relocation to the banks of the Klamath, the indoctrination and punishment endured at compulsory boarding schools, the near-eradication of their native tongue. “So we went through a period of, I guess you would say, a loss of identity, which leaves major voids in any individual that this has ever happened to,” he said.

People are not much different than animals, he said. A racehorse knows how to run instinctively. Fish know how to find the very same hole where they were spawned. People have hard-wired instincts, too, especially when they’ve been reinforced for thousands of years.

“We’re born to fish; we’re born to hunt; we’re born to gather,” O’Rourke said. “We’re born to carve and make boats. We’re born to be on the water and on the land. That’s where we spent our days. That was our school.”

In contrast, the tribe’s modern existence — with hunting and fishing strictly regulated despite the ostensible sovereignty of their nation, with school curricula defined by federal standards, with America’s trademark individualism disrupting the tribal community — runs counter to deeply ingrained instincts.

The resulting confusion and depression, O’Rourke suggested, are largely responsible for Native Americans’ high rates of substance abuse, domestic violence and now, here in Weitchpec, youth suicides.

“It’s a long process to how we got there, so it’s not a real easy fix by any means,” O’Rourke said. “Every individual is a little different, but it all spawned from the same place.”

O’Rourke speaks on the issue of suicide not just as tribal chair but also as a parent. His own son took his life nine years ago, and O’Rourke said that at points in his own life he, too, thought about suicide.

The long-term solution in Weitchpec, he said, is to restore balance to the lives of tribe members. The tribe has incorporated traditional knowledge and activities into the school curriculum alongside math and English. The Yurok language is now taught from preschool all the way through higher education. “Our language is starting to thrive,” O’Rourke said. It was salvaged and reinvigorated by looking backwards and drawing on the knowledge of previous generations.

“In that very same manner we will address and fix what causes suicide,” O’Rourke said. “We’re on the right track now.”

Pearson’s market, which carries hunting rifles, hardware and fishing gear along with the usual Doritos and Red Bulls.

Back at the community meeting, people are talking about youth activities. The Downriver Wrestling Club is wrapping up a very successful season. What should come next?

One man speaks up, saying there are plans to start a “stick club” for boys, where they’ll play the traditional Yurok stick game (see video below). Others suggest “Indian cards,” a traditional brush dance ceremony and a “fun dance” or “big time dance,” which an attendee describes as “a brush dance without the medicine part of it.”

After the meeting, Sylvia said the tribe’s suicide prevention efforts will take time. “I really would like to see what happens to the 5-year-olds in 10 years,” she said. “I really would like to see what the statistics look like to see if we’ve been effective as a community to make a difference.”

She’s encouraged by the influx of services from a broad spectrum of government agencies. They’ve helped to establish such a wealth of new services that the Weitchpec Tribal Office is now overflowing with classes, clinicians, drug prevention and relapse groups and more. Services will soon expand further thanks to the new modular building, which will add to the community’s modest infrastructure.

“But I think even more positive is the community has stepped up and said, ‘We want a change. We want something different for our children,’” Sylvia said. “If we keep moving at this momentum then we really are gonna get somewhere.”

# # #

If you or someone you know needs help, call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

This story was produced as a project for the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Traditional Yurok Stick Game from Visit Yurok Country on Vimeo.

CLICK TO MANAGE