Eureka City Councilmember Marian Brady, who’s now running for a seat on the Harbor District board, introduces Michael Marsden at the 53rd meeting of the Humboldt Bay Harbor Working Group in July.

A Sacramento-area man named Michael Marsden was the guest speaker at the July meeting of the Humboldt Bay Harbor Working Group, a collection of local rail enthusiasts who gather once a month over lunch at the Samoa Cookhouse. Fried chicken was on the menu, served “family style” at long tables, the way mill workers used to eat at the height of Humboldt County’s timber industry.

Michael Marsden. | LinkedIn

Marsden, white-haired, late 60s, wearing a gray sport coat over a black T-shirt, is a corporate executive, vice president of business development for a Newport Beach company called Pacific Charter Financial Services, and he was here, at the Samoa Cookhouse, to explain how Humboldt County can return to greatness. A greatness that exceeds the heyday of the Gold Rush and the timber industry. A greatness that will bring jobs, growth and prosperity the likes of which this region has never seen.

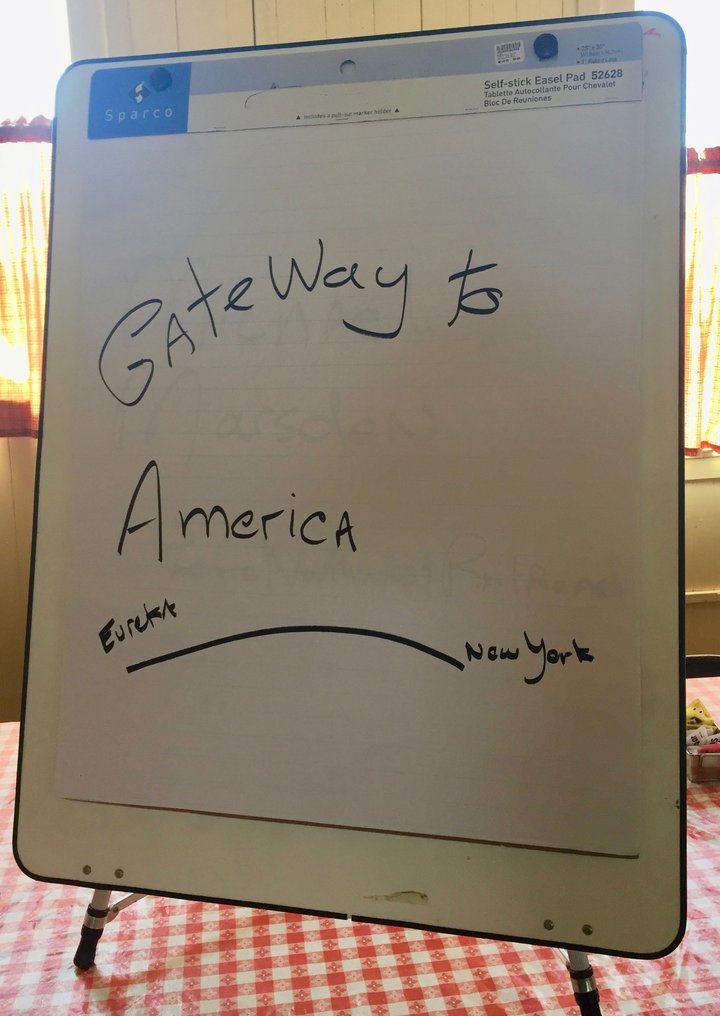

The idea is simple — so simple it can be drawn on a single sheet of paper like Norville Barnes’ “ticket upstairs” in The Hudsucker Proxy. In fact, someone had drawn it in black marker on an easel that stood behind Marsden as he spoke:

Eureka and Humboldt Bay can become “what we call ‘The Gateway to America,’” Marsden said. “You folks have an incredible asset here.” Our harbor can be transformed into a world-class through-port handling vast amounts of container shipping between Asia and the United States. But the opportunity is fleeting. The time to act is now.

What Marsden and his colleagues are proposing — namely, extensive port renovations and a new railroad between Humboldt Bay and the Central Valley — has been proposed before. Numerous times. But not like this.

The Sales Pitch

“What we’re proposing to do,” Marsden said, “is put an intermodal system in to allow the shipment of containers via hydrogen-electric engine … zero carbon footprint.”

Specifically, Marsden and his associates say they plan to renovate the harbor with three modern, automated marine terminals on the Samoa peninsula and not one but two new rail lines — one for eastbound trains and the other for westbound — running side-by-side for 220 miles between Humboldt Bay and the national rail network in the Central Valley, somewhere south of Red Bluff.

This infrastructure, they predict, will open the floodgates of international shipping. Humboldt Bay will become busier than the Port of Seattle, with nearly a quarter-million tons of cargo coming in and out each week. Shipping containers will be double-stacked onto train cars, and a fully loaded, 100-car train will arrive or depart from the Samoa Peninsula every three hours, on average, around the clock. These trains, they say, will be hauled by hydrogen fuel-cell engines, never mind the fact that there are currently no hydrogen-powered freight trains operating anywhere in the world.

Marsden told the assembled crowd at the Samoa Cookhouse that this state-of-the-art project will supercharge the local economy, providing hundreds if not thousands of permanent, union jobs paying wages of $40 per hour and up.

Governments will be flush, too. “The city budget of Eureka could triple or quadruple,” he said. We’ll have enough money “to fill in your potholes, to upgrade your streets, to improve your education system and health system.”

Promotional materials distributed at other meetings in recent months say we can also expect improved air service, higher business profits, and enough resources to “cope with societal ills such as homelessness, substance and child abuse, school dropout rates and despair.”

In other words, the train will cure what ails us. “Restoration of hope, optimism, and determination among the people of Humboldt County can be anticipated,” according to a project overview published last month.

All they need to get started, they say, is $10 million from the local community. That’s a fraction of the total price tag, which is expected to exceed $10 billion — $4 billion-plus for the railroad and $6 billion-plus for the marine terminals. Marsden and his colleagues say they need that $10 million from locals first. “That’s very important to us,” Marsden said to the assembled train fans. This “seed money” will kick-start the endeavor, showing government regulators and the as-yet-unidentified major financiers that there’s plenty of local support.

Who’s Behind the Effort?

Logo printed on materials handed out to potential investors.

This project, which has been trademarked as the Pacific Northwest Railroad, is the collective brainchild of a small group of locals and outsiders who have assembled an array of corporate entities.

Local attorney William Bertain, who has long argued that Humboldt’s future depends on resuscitating the railroad, joined with lumber/construction company owner Bob Figas, AquaDams CEO Nicolas Angeloff, retired co-owner of Pacific Marine Engineering Pete Oringer, and retired Butte County rice farmer William Helwer-Carlson as managers of a limited liability corporation called the Humboldt Eastern Railroad, or HERR. They’ve signed on to raise the $10 million in seed money from the local community. [Note: Figas is no longer involved in the LLC.]

Meanwhile, Pacific Charter Financial Services, Marsden’s employer, has been recruited to raise the balance of the $10 billion. The principals of the company are Alan Painter and Helen Gibbel-Painter, an octogenarian couple from Orange County.

Local proponents of the Pacific Northwest Railroad tout the Painters’ involvement as evidence of the project’s credibility. But what little information is available about them and their company online is less than inspiring.

The company’s name is misspelled on its own website.

For starters, Pacific Charter’s website appears to be falling apart. It’s filled with broken image links; the formatting has been stripped from most of the pages; and the company’s own name is misspelled on the homepage (“Finanical” rather than “Financial”).

The company phone number is just the Painters’ home phone, according to whitepages.com, while the mailing address belongs to El Toro Mailboxes, a storefront shipping center tucked between a Weight Watchers and a nail salon at a strip mall in the Orange County suburb of Lake Forest:

There’s a different business address on file with the Secretary of State’s Office, a Newport Beach address that comes up when you Google “Pacific Charter Financial Services,” though Google lists the business as “permanently closed.”

Indeed, the company’s California business license has been forfeited “for failure to meet tax requirements,” according to the Secretary of State’s Office. Pacific Charter remains incorporated in Nevada, where the Secretary of State lists the company value as just $25,000.

What have the principle players done in the past?

Alan Painter

- As director, president and COO of a company called Nano Life Sciences, Inc., Alan Painter attempted to raise $2.5 billion to create the world’s first “antimatter accelerator” that treats cancerous tumors. A confidential document provided to the Outpost notes that while the company failed to reach its $2.5 billion goal, it did manage to raise $35 million through the sale of Regulation D securities (meaning they weren’t registered through the SEC).

- Painter is listed as director and president of a company called D&Y Laboratories, makers of a “health aid” called Double Helix Water, which claims to treat everything from chapped lips and wrinkles to arthritis and autism by unblocking the body’s meridians and letting Qi flow freely (or something like that).

- Painter was also CEO of the now-defunct Eyeroo Corporation, which made more bold and unfounded scientific claims. (Here’s an archived screenshot of the company website.)

- Marsden is listed as vice president of Wind Power Business Development at Pacific Charter, though the company’s website no longer works. (Here’s an archived screenshot.)

- Marsden was also the chief financial officer of a failed upstart called the A-11 Professional Spring Football League. A 2011 story in the Mercury News noted that Marsden was attempting to line up “between five and 10 investors to raise the $100 million needed to launch the league.” Wikipedia now notes, “As of 2018, nothing more has been heard from the (presumably former) A11FL.”

Ken Davlin

Reached by the Outpost, Marsden said Pacific Charter’s services were enlisted by Kenneth Davlin, president of Eureka engineering firm Oscar Larson and Associates. Davlin, whose career has included stints as the city engineer for Blue Lake, Trinidad, Fortuna, Rio Dell and Ferndale, is now serving as the engineer of the Pacific Northwest Railroad. He was on hand to answer technical questions at the Samoa Cookhouse meeting in July, and the PNR now has an office established in a Davlin-owned building at 317 Third Street in Eureka.

Reached by phone on Tuesday of last week, Davlin said he wasn’t sure if he was allowed to speak with the press. He suspected that Pacific Charter would assign a spokesperson for the project and said he expected to find out for sure later that day. Since then we’ve left several messages for Davlin — with the receptionist at Oscar Larson and on Davlin’s cell phone — but we have yet to hear back.

The Plan (Such as It Is)

If we assume these folks actually intend to build the Pacific Northwest Railroad, its $10 billion price tag is just one of many enormous challenges. The tasks would include engineering double tracks atop some of the most unstable geology in the continental United States, mitigating countless environmental concerns, gaining government approvals at the local, state and federal level, earning buy-in from residents of at least three counties, and establishing easements for a right-of-way that runs through Manila, Arcata and Blue Lake in just the first 15 miles.

“My concern is Manila and other communities,” said Rich Tobin, who lives with his wife Cathy in the small community on the peninsula. “The railroad tracks go right through it,” he said. “It would cut our community in half.”

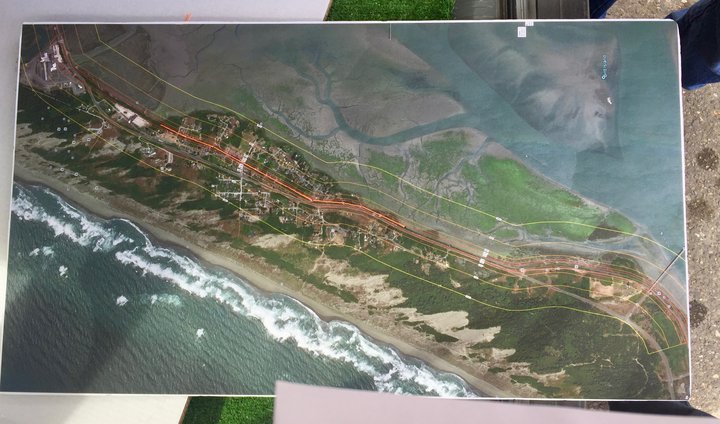

Tobin had shown up for an interview with a three-ring binder packed with paperwork — research he’s been doing into the Pacific Northwest Railroad. He has used data provided to local groups in recent months, even though much of that data, including the expected shipping volumes, operational costs and return on investment, don’t seem realistic. And those data are often expressed in measurements and terminology that aren’t standard in the shipping industry.

Regardless, Tobin is taking project proponents at their word, using their facts and figures along with his own research to make a variety of calculations. For example, using the county’s Geographic Information System web app he figured out that more than half of the dwelling units in Manila are 500 feet or less from the centerline of the existing rail right-of-way, currently held by the North Coast Railroad Authority.

He’s even used satellite imagery to create large-scale maps, which he has used to help visualize the impacts of the proposed rail. Below, for example, is a map he created using orange yarn to depict the length of one train.

Map created by Manila resident Rich Tobin. | Photo by Ryan Burns.

Tobin and his wife worry about the ensuing noise, the traffic of commuting dock workers, the effects on emergency vehicle access, and the prospect of their neighbors’ homes getting seized through eminent domain.

“We moved up here in the late ‘80s, and we fell in love with it because of the pristine beauty,” Cathy Tobin told the Outpost. “And this train idea is really very troublesome to me for many reasons.” Her main concerns, she said, involve the potential for environmental degradation, including threats to our local oyster industry, the increased potential for wildfires, noise pollution and the impacts to the sandy soils on the peninsula.

“In my opinion, this thing is a really bad idea,” Cathy Tobin said.

Asked at the Samoa Cookhouse meeting how wide an easement will be required to accommodate double tracks, Davlin said, “There is no simple answer for that.” He went on to say that the easement will be around 150 feet wide and likely wider as it winds through the mountains. Since the federal government no longer allows at-grade railroad crossings, the tracks on the peninsula may have to be elevated, according to Davlin.

Then there’s the fact, noted above, that while hydrogen fuel-cell technology is being used in other countries to pull regional trains and passenger light rail, it has yet to be adopted anywhere for the purpose of hauling freight trains.

One of the leading experts in the field, Dr. Andreas Hoffrichter, director of the Center for Railway Research and Education at Michigan State University, told the Outpost via email, “The technology has the potential to be scaled-up to mainline freight, though [it is] not yet proven.”

Indeed, a piece published earlier this year in the industry magazine Rail Engineer highlighted the technology’s potential for light rail while cautioning, “[T]he space required to store hydrogen is such that its use to fuel freight locomotives or high-speed trains may not be viable.”

“I’m doubtful that an east-west railroad would work with any technology,” said Arne Jacobson, a professor of environmental resources engineering and director of the Schatz Energy Resource Center at Humboldt State University. “Hydrogen would just make it harder.”

Other elements of the plan require similar leaps of faith, if not the willful suspension of disbelief. For example, a “financial analysis” provided at one recent meeting estimated that each double-engine train, hauling 200 containers holding roughly 8,000 tons of cargo, will average 50 miles per hour between the Humboldt Bay and the Central Valley. This despite the fact that, as a previous east-west rail study notes, the federally enforced speed limit for freight trains on Class 3 rail lines is just 40 miles per hour, and when trains go downhill or around all but the most gradual corners they have to go even slower.

What’s at Stake

It’s worth a minute to ruminate on that $10 billion figure. By way of comparison, a 2013 study from BST Associates and Burgel Rail Group [click here for the pdf] was considered by many a sobering dose of reality for rail fantasists because it concluded that such a project would cost more than one billion dollars.

In order to be economically feasible, even at one-tenth the cost of the Pacific Northwest Railroad plan, Humboldt Bay would have to export between 11.5 million and 18.5 million metric tons of bulk cargo per year — more than the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Stockton, Long Beach or Los Angeles, the BST study found. (The study used bulk cargo rather than containers because, according to the authors, “bulks represent a stronger potential market for a Humboldt rail line at this time.”)

In short, the study found that a rail would likely be “both high cost and high risk,” with annual maintenance costs around $20 million dollars.

Of course, the east-west rail concept has long been about more than just facts and figures. Ever since former Harbor District CEO David Hull’s termination in 2011 there has been a political divide in Humboldt County between those who believe we should throw all of our weight behind train revival efforts and those who prioritize more easily attainable goals.

Current Harbor District CEO Larry Oetker said his current priority is creating “a 21st Century port,” which involves building a new multi-purpose dock and slightly reconfiguring the alignment of the south jetty to reduce shoaling, “so you wouldn’t have to dredge all the time.”

As for the train, Oetker echoed the stated opinions of former CEO Jack Crider and several current members of the Board of Commissioners. “We’re not opposed to the railroad; we’re just not resting our hat on the railroad.”

Image from Marian Brady’s Harbor District campaign literature.

Eureka City Councilmember Marian Brady, a loyal member of the Humboldt Bay Harbor Working Group, is now running for a seat on the Harbor District Board of Commissioners, and she’s making the railroad a central theme of her campaign, even going so far as to suggest, without evidence, that the 2013 BST rail study mentioned above was a fraud. (We reached out to Brady last week via email requesting more information but have not heard back.)

Anthony Mantova, a business owner and candidate for Eureka City Council, has a page of his campaign website dedicated to the hydrogen train plan. “I am one of the first politicians to publicly endorse the Pacific Northwest Railroad,” his site says. “Any way you do the math, the rail line will produce record-level tax revenues for the City of Eureka.”

Humboldt County Supervisor (and former Harbor Commissioner) Mike Wilson said that while he hasn’t examined the Pacific Northwest Railroad plans in detail, he’s skeptical.

“It seems more like a political and culture war issue than a real project,” Wilson said. “And I would caution our community on making long-term land use and economic development decisions based on what seems to be an unrealistic proposal.”

The Money

Project proponents are still trying to raise the first $10 million from the local community. In December Bertain’s company, the Humboldt Eastern Railroad, began offering shares of stock at a dollar per share. The goal, according to a “Confidential Private Placement Memorandum” prepared by San Francisco attorney Ben Fackler, was to find 215 people willing to buy blocks of 50,000 shares, or “Class A Units.”

The proceeds, they say, will be used to fund studies, reports, fees, permits, etc. As an incentive, this first wave of investors will be able to collect four times their money back, according to offering, just as soon as Pacific Charter brings in its first $100,000 $100 million in gross proceeds from a subsequent stock offering.

The second phase of funding will be another private stock offering, this time for $500 million worth of shares with the proceeds going to the purchase of U.S. government bonds, according to the memorandum. That will just leave about $9.5 billion left to raise, and the memo says Pacific Charter “currently expects to raise this sum through a series of additional offerings of Series C Preferred Stock.”

The Outpost asked Marsden for details. “We are corporate bond specialists,” he said. “We work closely with many of the top-end industry people that do corporate bond financing.” Asked specifically who will buy the Series C stocks, Marsden said those transactions will be handled through broker-dealers. “If you look at the top names in Wall Street, those are who we work with,” he said. “We sell to their clients.”

According to a budget prepared for submission to the Surface Transportation Board, the people proposing this project stand to make significant profits regardless of whether or not the development gets fully financed or built. For example, Kenneth Davlin’s engineering firm, Oscar Larson & Associates, is slated to receive $980,000 for “technical project management and monthly reports.”

The initial stock offering, to its credit, makes it clear that local investors stand to lose all of the $10 million they’re being asked to invest. The document explains that HERR can’t guarantee that it will get the required financing, permits and approvals “in a timely manner or at all.”

Later it adds, in all caps:

THERE IS NO MARKET FOR THE COMPANY’S SECURITIES. NO INVESTMENT IN THE CLASS A UNITS SHOULD BE MADE BY ANY PERSON NOT FINANCIALLY ABLE TO LOSE THE ENTIRE AMOUNT OF SUCH INVESTMENT.

The red flags keep coming. “Neither the Company [HERR] nor the Manager [Bertain] has any operating history or has been involved with infrastructure projects like [this one] or investments like [this one].”

Furthermore, the Company “is not registered, and does not intend to register, as” an investment company because if it did the Company “would become subject to substantial regulation.”

Regardless, project proponents continue to say that this project is “likely the key to revitalizing our regional economy,” as a confidential financial plan insists.

That document goes on to reiterate the importance of local support. “It has been observed that the overwhelming reaction of the public in our region to the notion of an East-West Rail is that [it] is a great idea, and that it would be good if it could be done.”

They just need $10 million from locals willing to bet that it can.

CLICK TO MANAGE