McCloskey speaks at his campaign launch in Ferndale last month. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

Allen McCloskey is a natural politician. Handsome and charismatic, he has placed himself on the front lines of recent health care union battles, political campaigns and other public demonstrations. And he has the marketing savvy of a PR wiz, creating his own logos, political memes and promotional videos.

A logo McCloskey posted on Facebook in January.

With a political playbook borrowed from Bernie Sanders and a knack for public speaking, McCloskey has become a prominent activist and rabble-rouser, a celebrity of sorts among the impassioned progressives who’ve gained all the momentum in local politics of late.

Last month McCloskey launched his campaign to replace Rex Bohn as the First District representative on the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors. Surrounded by supporters, McCloskey touted his progressive bona fides while painting Bohn as a conservative good ol’ boy who’s fond of backroom deals.

McCloskey’s campaign slogan, superimposed on an image of him in a big cowboy hat, is “Transparency. For a change.”

In his candidate biography, McCloskey says he helped spearhead the effort to unionize employees of Redwood Memorial and St. Joseph Hospital. (He works at the latter as a lab technician assistant.) He was involved, to varying degrees, in the recent campaigns for Measure V, the countywide initiative establishing rent stabilization at county mobile home parks, and Measure P, Eureka’s “true ward” voting system overhaul.

In recent years he has proudly publicized his role as an Assembly delegate to the California State Democratic Party. There are about 3,200 such delegates statewide, and they form the party’s voting body at annual conventions.

McCloskey has also shown a willingness to challenge authorities. In 2016, he and his husband, along with another gay couple, sued St. Joseph Hospital for discrimination. (The case was settled out of court.) And last year he was among a local group of progressive Democrats who called for U.S. Rep. Jared Huffman, state Senator Mike McGuire and state Assemblymember Jim Wood (Democrats all) to be stripped of their party delegate status for endorsing conservative incumbent county supervisor Ryan Sundberg rather than his Democratic challenger, Steve Madrone. (That effort failed.)

In 2016 McCloskey briefly ran for a seat on the Eureka City Council before dropping out after a health scare. And in 2018 he toyed with the idea of running for Eureka mayor but backed out, he says, to clear the way for Susan Seaman, who won the election.

This run for county supervisor represents McCloskey’s arrival to the main stage of Humboldt County politics, and so it was inevitable that he’d have to answer questions about some incidents in his past that have been fodder for local gossip and anonymous internet activists.

After looking into some of the incidents, the Outpost found that McCloskey has been accused of some serious misdeeds over the years, including fraud, embezzlement and perjury. And when I sat down with him for an interview on Friday, he had a hard time explaining these events, growing increasingly flustered and taciturn over the course of an hourlong conversation.

# # #

Before getting to the interview, let’s take a look at some of the incidents in question.

In 2004, McCloskey was living in Washington state, working for a Seattle-based company called Kleen Environmental Technologies, Inc. Still in his early twenties, he’d been hired as a development consultant and charged with getting the company a permit from the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (WUTC). This permit would have given Kleen the right to collect, transport and dispose of biomedical waste in the region.

But biomedical waste disposal happens to be a competitive business, and several of Kleen’s Northwest competitors challenged the application, saying they had those services covered. One of those challengers, the multinational corporation Stericycle, hired an attorney named Stephen B. Johnson, who proved to be a dogged investigator and thus something of a nightmare for McCloskey.

According to documents on file with the WUTC, here is what happened in the fall of 2004:

On October 12, McCloskey faxed to the WUTC one of several letters of support he submitted for Kleen’s application. This particular letter, which you can see a copy of here, was printed on what appeared to be official letterhead of the National Indian Health Board (NIHB).

“[I]t is imperative that we see this application granted. …,” it says. “The service that we have received from Kleen over the last eleven year [sic] has been nothing short of pleasant.”

This letter was purportedly from a man named Lancing Birdinground, identified in the document as an executive regional board member representing “region ten of the National Indian Health Board” in Kingston, Illinois.

Johnson, the attorney for Stericycle, was skeptical, so he started digging. And eight days after the Birdinground letter had been submitted, Johnson sent an email to the administrative law judge overseeing the WUTC hearing telling her that the letter was a fraud.

As proof he presented a letter from the executive director of the NIHB, J.T. Petherick. This letter was printed on the actual letterhead of the agency, and it explained that the NIHB had no association with anyone named Lancing Birdinground; the agency has never had an office in Kingston, Illinois; and there’s no such thing as “region ten” of the NIHB since the agency doesn’t operate under a regional system.

Johnson also provided letters from the Quileute and Swinomish Indian communities saying effectively the same thing: They’d never heard of this Lancing Birdinground, and if he exists he certainly doesn’t speak for them.

When McCloskey learned that the authenticity of the Birdinground letter was being questioned, he quickly asked for it to be removed from the application. But the judge didn’t let the matter slide. Instead she scheduled a hearing “to allow the parties to cross-examine the witness who presented the questioned document [McCloskey] and to argue the consequences of the information.”

The matter came to a dramatic head on October 26, 2004. Attorneys from the companies challenging Kleen’s application, including Johnson, first cross-examined Kleen owner Robert Olson.

An attorney named Jim Sells asked Olson about why he’d placed McCloskey in charge of this application. Olson said he’d been impressed with McCloskey’s education, which, according to his résumé, included a bachelor’s degree from Humboldt State University, and by his claim of having worked in his father’s construction business.

Here’s an excerpt from the hearing transcript:

Sells: Did you contact any other employers he may have had?

Olson: No.

Sells: So as far as you know, he was straight out of college and worked for his father.

Olson: I don’t know that. I believe there was a period of time he worked for his father.

Sells: Did you check with his father to see if that was true?

Olson: No.

Sells: Did you do a background check?

Olson: No, sir, I did not. …

Sells: Did you check with Humboldt State to see if he actually graduated?

Olson: No, sir.

The résumé wasn’t on file with the hearing before the WUTC, but McCloskey had also claimed in a sworn declaration, under penalty of perjury, to have earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from HSU in 1993. (Since he was born in November of 1981, that would have made him 11 at the time of graduation.)

The Outpost did check with HSU. The school has no student record for him.

When it was McCloskey’s turn to testify, he said he had been shocked to learn that the Birdinground letter was fraudulent. He also claimed to be unaware of the National Indian Health Board altogether and to have no idea who Lancing Birdinground is.

Johnson grilled McCloskey about the Birdinground letter, asking exactly when and how he’d received it, why he’d opened it, considering it hadn’t been addressed to him, and whether he’d shown it to anyone else or attempted to verify its authenticity.

McCloskey was evasive, and his story seemed to have some flaws. He claimed, for example, to have received the Birdinground letter in the mail on October 11, though it was dated Oct. 12.

“But that didn’t strike you as strange?” Johnson asked.

“At the time, no,” McCloskey said.

Johnson again asked McCloskey if he knew Lancing Birdinground. McCloskey said he did not and Johnson replied, “Mr. McCloskey, would you be surprised to know that Lancing Birdinground knows you?”

“Yes, yes,” he responded.

Johnson then addressed the judge. “Your Honor, I would like to mark for the record another exhibit. This is a fax to me on October 25, 2004, with a declaration attached that I received yesterday by fax from Lansing Birdinground.”

Johnson, the dogged investigator, had tracked down the real Birdinground, a member of the Crow Indian Tribe living in Big Horn County, Montana, and convinced him to submit a sworn declaration. (It can be found on p. 94 of this document.)

“My name is Lansing Birdinground,” the declaration begins. He goes on to say that he’d reviewed the letter attributed to him (noting how it misspelled his first name) and said he had nothing to do with its preparation. The signature on it didn’t belong to him; he had no connection to the NIHB; and he had no business relationship with Kleen Environmental Technologies, Inc. But one thing was familiar.

“I do know Mr. Allen McCloskey,” he testified.

Birdinground said that in 2001 he’d briefly been manager of the Little Bighorn Casino, in the tiny community of Crow Agency, Montana, and the casino had been sent a brochure from a company called McCloskey Enterprises, advertising consulting services for tribal casinos. Birdinground reached out, and in July 2001 McCloskey and another gentleman visited the casino on their own dime. McCloskey, Birdinground testified, stayed with him and his family, eating meals in their home.

“I remember Allen McCloskey very well,” he said in his declaration. “He seemed to be well informed on Indian gaming issues. He was a nice guy. He was young. Since his visit to our area in 2001, I have had no contact with Allen McCloskey.”

“Mr. McCloskey,” Johnson said, resuming his cross-examination, “have you had a chance to read Mr. Birdinground’s declaration?”

“Yes, I have,” McCloskey answered.

“Do you want to change your testimony now?” Johnson asked.

McCloskey declined, saying that while he remembered visiting the casino in Montana, he didn’t recall meeting Birdinground.

Johnson and McCloskey went back and forth for quite a while, with Johnson asking for details about McCloskey’s memory of events, his handling of the Kleen application, and his personal and professional background.

“Mr. McCloskey, would you tell us a little bit about McCloskey Enterprises?” Johnson asked. “Where is it located?”

“In Eureka,” McCloskey answered.

“Eureka, California? Is that its principal office?”

“Yes,” McCloskey said.

He testified that McCloskey Enterprises was his dad’s company, and he wasn’t personally a shareholder, owner or principal.

Johnson asked, “Would you be surprised to learn there is no record of McCloskey Enterprises as a corporation in the California Secretary of State’s database?”

“Personally, I wouldn’t,” McCloskey said.

“Not a matter of significance for you,” Johnson observed.

“No.”

Johnson then asked the judge if he could introduce more evidence: a copy of pages from a McCloskey Enterprises website identifying Allen McCloskey as a “principal.” It also said McCloskey Enterprises had offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Dallas, New York City, San Diego and Seattle. (The address listed for the Seattle office was, in fact, that of Kleen Environmental Technologies, McCloskey’s employer.)

These website printouts were marked as exhibit 227, but before McCloskey could answer any questions about it, he asked to take a break. He never returned to the witness chair.

Two months later, the judge issued her ruling, denying Kleen’s request on the grounds that the company had presented false and misleading information. Her synopsis of the facts notes:

After being confronted with Exhibit 227 during the hearing, Mr. McCloskey either fell ill or feigned illness and was taken by ambulance to St. Peter’s Hospital in Olympia, Washington, requiring the proceeding to be recessed.

Since October 26, 2004, Mr. McCloskey has stopped communicating with counsel and representatives of Kleen Environmental Technologies, Inc., has apparently resigned from Kleen Environmental Technologies, Inc., and may have moved to the state of California, removing himself from the jurisdiction of the state of Washington.”

The Outpost recently tracked down some of the attorneys who were involved in this hearing. Reached by phone, Johnson, who is now retired, said he remembered it well. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime type of case,” he said. “To catch a guy so completely in presenting falsified documents is impressive.”

I emailed him photos of McCloskey, and he said it looks like the guy he remembers, though he couldn’t be 100 percent sure.

Greg Haffner, the attorney who represented Kleen, was a bit more certain. “Yes, it appears to be the same person,” he said after receiving photos of McCloskey.

Jim Sells, who represented some of the companies that challenged Kleen’s application, also remembered McCloskey. “The guy was just a fraud; he was,” Sells said when reached by phone. “Fairly young guy, pretty well spoken guy. But he was lying. The whole time.”

Emailed an older photo of McCloskey, Sells replied, “That’s him!”

# # #

A couple years after the events in Washington, McCloskey got a job at the Eureka Plaza Design, an upscale boutique and furniture shop that was owned at the time by former Trinidad Mayor Julie Fulkerson. His employment there didn’t last long. More on that later.

In 2007 McCloskey helped launch a bottled water company under the label Native Springs. “It’s an all-natural, energized spring water,” McCloskey told the North Coast Journal that year. He said the water, which was bottled by the now-defunct McClellan Mountain Spring facility on the Samoa Peninsula and sold for $1.79 per plastic bottle, had been blessed by Yurok elders. “[O]ur people believe it’ll bring emotional, spiritual and mental balance to all who drink it,” he said.

In the fall of 2009 McCloskey ran for a seat on the Yurok Tribal Council but lost to the incumbent by a vote of 17-12, according to the Yurok Today newsletter.

About a year and a half later, in May 2011, McCloskey landed a job as tribal administrator for Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians, a Lake County tribe with about 300 enrolled members. He worked there for a little less than two years before vanishing under a cloud of suspicion, according to the tribe.

In fact, the allegations from the Scotts Valley tribe bear some striking similarities to those levied against him in Washington a few years earlier. As with the WUTC, the Scotts Valley tribe accuses McCloskey of lying, creating fraudulent documents under a false identity and then, once questions arose, disappearing altogether.

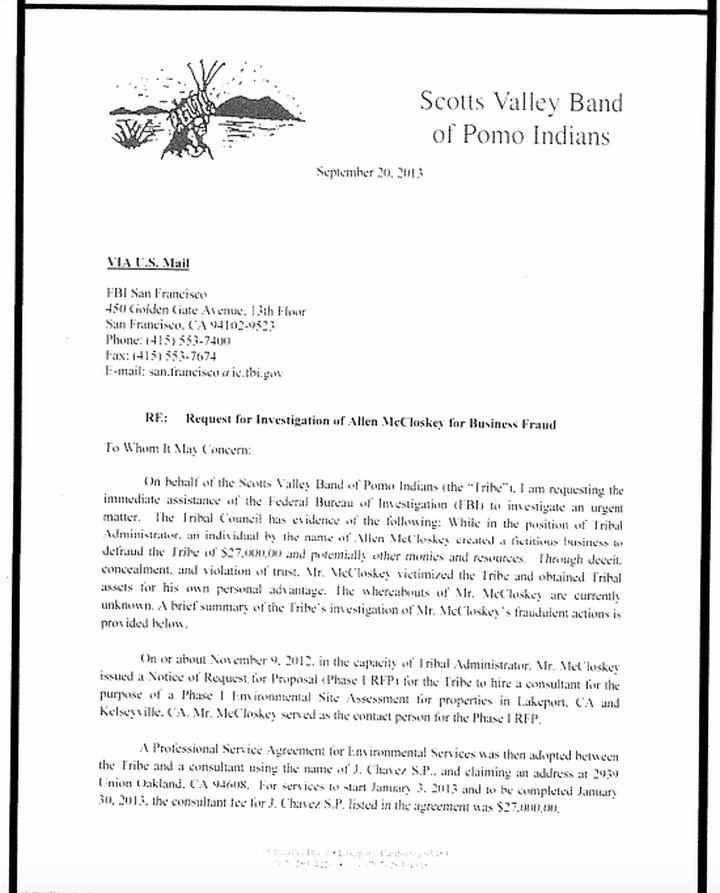

In September of 2013, about five months after McCloskey left, the Scotts Valley tribe sent a letter to the FBI office in San Francisco asking the agency to investigate McCloskey for fraud and embezzlement.

Letter from the Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians to the FBI, requesting an investigation of McCloskey for fraud and embezzlement.

“Through deceit, concealment, and violation of trust, Mr. McCloskey victimized the Tribe and obtained Tribal assets for his own personal advantage,” the letter says.

According to this letter, signed by then-Tribal Chairman Donald Arnold, here’s what McCloskey did during his employment with the tribe: In his capacity as tribal administrator, he’d been put in charge of hiring a consultant to perform an environmental site assessment on some tribe-owned properties in Lakeport.

With McCloskey also serving as the contact person for this hire, the tribe wound up signing a contract with a consultant who used the name “J Chavez Environmental, SP Inc.” In paperwork, the company claimed an address on Union Street in Oakland, and a “J. Chavez SP” sent the tribe an invoice, care of McCloskey, for $27,000.

The tribe issued a check in that amount to the Oakland address, and the following month J Chavez Environmental, SP Inc. sent McCloskey a letter “with what is apparently claimed to be” the requested environmental assessment and report. Not until months later did tribal officials inspect this paperwork, and when they did they found that the environmental report “provides little to no data.” It didn’t even identify the property involved.

Tribal officials apparently didn’t get suspicious about any of this until after McCloskey’s “abrupt” resignation in April 2013, “at a time when he was already under suspicion for the improper use of the Tribe’s credit cards and mismanagement of tribal funds” amounting to more than $7,500, the letter says.

When the tribe did get around to investigating the environmental consultant paperwork, they found that the address listed for “J Chavez Environmental, SP, Inc.” belonged to a junkyard in Oakland, and the company’s phone number, which had a Seattle area code, was inactive.

Furthermore, “J Chavez Environmental” didn’t appear to be a real business licensed in California, though the junkyard address was claimed by a business called Tacos Chavez. And McCloskey, the tribe says in its letter, was in possession of a catering vehicle identified as serving Mexican food.

In summary, the letter from the Scotts Valley tribe alleges “that Mr. McCloskey created J.Chavez Environmental, SP, Inc. as a fictitious company in order to defraud the Tribe of $27,000.00 to purchase a catering vehicle, a taco truck, for his personal use and benefit under the name “Tacos Chavez.”

The FBI responded a couple weeks later, declining to investigate because the dollar amount in the alleged crimes didn’t meet the U.S. Attorney General’s prosecution threshold.

The Outpost reached out to the Scotts Valley tribe, and in February current Tribal Administrator Tom Jordan sent an email saying that with no law enforcement agency willing to investigate the tribe’s claims, and given the tribe’s own limited resources, the matter remains unresolved.

McCloskey may not have faced any legal repercussions from these events, but ever since the Scotts Valley letter was published by an anonymous blog back in 2016, it keeps coming up in conversations and internet comment threads.

Last month, McCloskey posted a “campaign memo” on social media saying that the tribe’s accusations against him are “patently false and manufactured.” In fact he says that on March 30, 2013, before he resigned his position, he sent a letter to the Bureau of Indian Affairs blowing the whistle on the tribe itself for “financial irregularities” he’d uncovered. The tribe’s accusations, he says, were just an attempt at retaliation.

“Mr. McCloskey’s legal counsel responded with solid proof, including a forensic audit, discrediting those accusations as politically motivated and unsubstantiated,” his statement says.

The Outpost sent a copy of McCloskey’s campaign memo to the tribe, and a couple days later they emailed a statement saying that tribal council members who were in office at the time of McCloskey’s employment “unequivocally maintain” that his version of events misrepresents the facts. As far as they’re concerned, he got away with fraud and embezzlement.

From the statement:

While a civil lawsuit seeking recovery of the government funds from Mr. McCloskey was considered, the Tribal Council determined, upon advice of counsel, that the cost to the tribal government would likely exceed any recovery.

The Tribe did send a demand for repayment to Mr. McCloskey. Our letter went unanswered. With little chance of recovery, the Tribe turned its attention to other matters.

As for the letter McCloskey supposedly sent to the BIA in 2013, no one on the council had heard anything about it, the statement says, adding, “We have found no record of such an investigation.”

The Outpost reached out to the BIA to see if they had any record of such an investigation. After a few days a spokesperson for the agency, Nedra Darling, said that the agency’s staff investigated, and while their search was by no means comprehensive they hadn’t found any such letter.

# # #

On Friday afternoon, McCloskey sat down for an interview at the Ramone’s in Old Town. He’d brought with him a three-ring binder that appeared to be filled with campaign materials, and he was accompanied by a young progressive activist named Andie White, who he described as a factotum for his campaign.

Our interview started with a question about the candidate biography, which appears on his campaign website and on Facebook page.

Lost Coast Outpost: Your candidate bio mentioned that you studied abroad?

Allen McCloskey: Uh huh.

LoCO: Can you tell me about that?

AM: Yeah. Yeah, so um, gosh, I mean I’ve gotten so many certifications in hazardous waste handling to hazardous waste transporting.

LoCO: Where did you study abroad?

AM: Argus Pacific.

LoCO: I’m not familiar with that.

AM: They’re a certification group for things like hazardous waste handling and transportation.

LoCO: Where are they located?

AM: Well, I took the course in Seattle.

[Note: according to the Argus Pacific website, their only location is in Westlake Mountlake Terrace, about 14 miles north of Seattle.]

LoCO: Oh. So that’s not abroad, is it?

AM: [pause] Well it’s not here.

LoCO: Is that what you meant by “abroad”?

AM: Yyyeah. Yeah, I would say. Yeah.

A few minutes later I asked McCloskey what became of the Native Springs Foundation. According to documents on file with the California Secretary of State’s office, the nonprofit was dissolved in 2015.

“We really wanted to build something that one of the tribal entities could take over and run with, but we just couldn’t get the interest,” he said. “If you think the politics of the county is something, I mean tribal politics is its own beast. Trying to get anybody to come to the table … . It just ended up not happening, which was unfortunate … .”

Next I asked McCloskey about his brief run for a seat on the Eureka City Council in 2016, when he withdrew just hours before the candidate filing deadline due to a health issue. He explained that early in that campaign, while canvassing in Eureka, he collapsed in someone’s yard.

“It was so sudden,” he said. “I literally just fell over.”

A CT-scan revealed that he had a mass in his pharyngeal space, at the back of the throat, he said, and a local doctor, an ear, nose and throat specialist, referred him to the Stanford University Medical Center where he underwent a PET scan and, eventually, CyberKnife treatment.

There was a concern, he said, that the tumor could be precancerous, but since the surgery it has shrunk. Now he feels great.

“I mean, it bothers me that it’s there. … But what can you do?” he said.

Eventually I asked McCloskey about his campaign memo denying the allegations from the Scotts Valley tribe. I told him that tribal council members denied his version of events and asked if he could provide the Outpost with a copy of the letter he allegedly sent to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He said that he didn’t have it on him, but when asked if he could forward a copy he said, “Sure.”

Despite multiple requests since our interview he has yet to do so.

I also asked if he could forward copies of the “solid proof” his attorney found exonerating McCloskey of any wrongdoing.

”Well, I’d be happy to,” he said, but then he hesitated. “I don’t want the story to be solely about that. It needs to be more about why I’m running.” He went on to say that there are some things he can’t release because he signed a confidentiality agreement with the tribe. “But I think we can provide you enough to give you a narrative and a timeline,” he said.

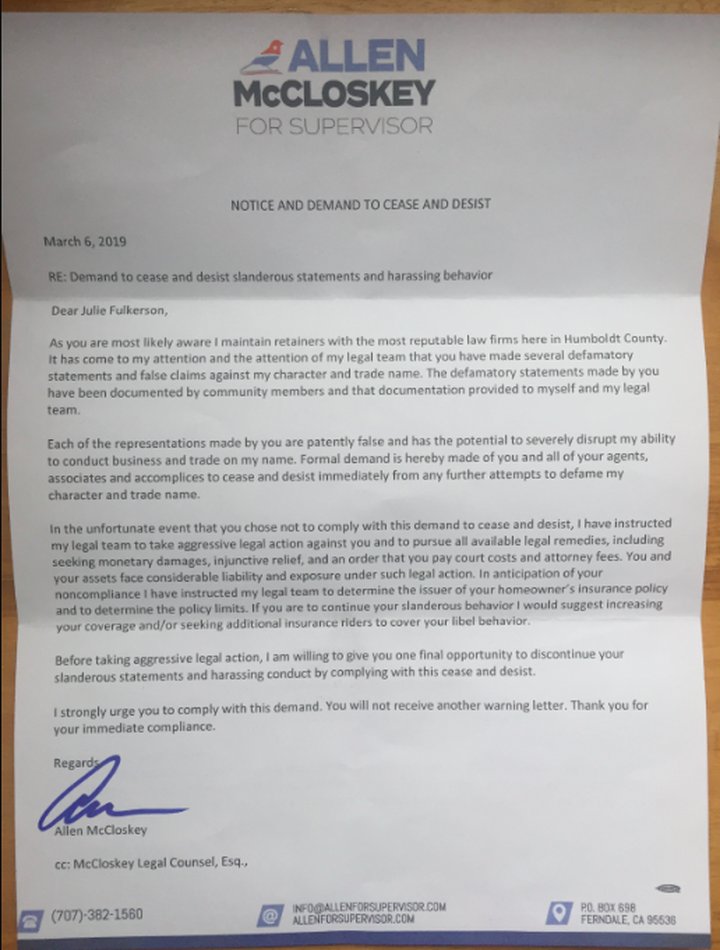

Recently, while researching this story, McCloskey’s former Plaza Design employer, Julie Fulkerson, showed us a letter she’d received from him. Printed on his campaign letterhead, it was labeled “NOTICE AND DEMAND TO CEASE AND DESIST,” and it read, in part, “It has come to my attention and the attention of my legal team that you have made several defamatory statements and false claims against my character and trade name.”

McCloskey’s letter to Fulkerson.

It doesn’t specify what the alleged statements and claims were about, but it says that if Fulkerson doesn’t comply with McCloskey’s demand to cease and desist, he has instructed his legal team “to take aggressive legal action” against her. (See the full letter here.)

Asked what this letter was about, McCloskey said it concerned politics. “I had my disagreements with her while she was mayor of Trinidad,” he said. “I know she very much disagrees with my progressive stance within the Democratic party, holding our elected officials accountable to their constituents.”

But he didn’t want to get into the specifics of what she has allegedly said about him. When pressed on that question he finally responded, “Well, she said a lot of things. Some of them were blanket statements like I’m a liar. She repeated a lot of the Pomo stuff. You know, asserting facts without documentation. And that’s, that’s dangerous, especially for someone with assets like Julie Fulkerson.”

Reached for comment, Fulkerson said, “I have never said that I disagree with his politics. I’m likely to the left of Allen. I consider myself a Socialist but am registered Democrat.” She also denied talking about the Pomo allegations, saying she’s not informed about them. And she insisted she’s never lied about McCloskey. Anything she’s said about him concerned his behavior while in her employ.

McCloskey hadn’t mentioned his job at Plaza Design but when asked he acknowledged working there for a short period of time.

About 20 minutes into the interview I started asking McCloskey about his time with Kleen Environmental Technologies and the hearing before the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission. The line of questioning seemed to make him uncomfortable. Normally loquacious and articulate, he was soon struggling to find words and giving short, confusing responses.

Below is a partial transcript of our conversation, which has been minimally edited and condensed for clarity.

Lost Coast Outpost: Can you tell us about [your time with Kleen and the hearing before the WUTC]?

McCloskey: Mm-hm. Yeah. That’s a tough one. I’m not sure how we tell that story without getting into my personal life too much. As a young man I dated an older gentleman who — how should we say? — was not a legal citizen. Long story short, he ended up using my information to be employed, um, in the capacity that he was with the company. There was a lot that went on there. After he and I separated and I moved back here to Humboldt County, I mean, I started getting phone calls about this. About the company, about a hearing, about all these different things. And long story short, we responded to that. I had to provide a copy of my ID to the administrative law judge, to the King County Sheriff Department. I mean, there was a list of things I had to do to —

LoCO: Are you saying it wasn’t you?

AM: Yeah.

LoCO: It wasn’t you who testified before the commission?

AM: Yeah, no.

LoCO: It was identity theft?

AM: Yeah.

LoCO: I have been in touch with some of the attorneys who were there and sent them pictures of you, and they said it’s the same guy.

AM: Mm-hmm.

[Silence.]

LoCO: So how do you explain that?

AM: No, it’s, it’s, if it was? I mean, I would be responsible for that. If I did that there would be legal consequence for that. So.

LoCO: But the administrative law judge ended up saying that you, in the middle of testifying, during a break, you had some sort of medical emergency and were taken to the hospital …

AM: Uh huh.

LoCO: … and then never returned.

AM: Okay.

LoCO: And left the state of Washington, thereby leaving Washington’s jurisdiction.

[Long pause.]

AM: It’s all a bit bizarre. I mean, I go back to the state of Washington. I have family in the state of Washington.

LoCO: But was that you who had the medical emergency in the hearing?

AM: No.

LoCO: It was your ex-boyfriend?

AM: Yes.

LoCO: Then how do you explain that the attorneys who were involved in this proceeding say you’re the same guy?

AM: I don’t know, Ryan. I don’t know why they would say that.

LoCO: Huh. When did you stop working for Kleen? Before or after this investigation?

AM: I worked for Kleen as an intern. That’s where I met the gentleman, um, that I ended up dating.

LoCO: So, identity theft. What happened with that case?

AM: Well there wasn’t any financial capacity to it. It wasn’t like I had any credit card that was used or accounts that were opened or anything like that. I tried to make contact with him; I tried to make contact with other people with the company that had phone numbers for him. I was just totally cut off. No communication.

LoCO: I’m just having a hard time following this because I looked at your sworn statement from that hearing.

AM: Mm-hmm.

Above: signature from McCloskey’s sworn declaration before the WUTC in 2004. Below: signature from filings for the Native Springs Foundation, 2008.

LoCO: And your signature seems to match your signature from other things, more recently.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: In that sworn statement you said, for example, that you graduated from HSU.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: But that’s not correct, right?

AM: Mm-hmm. No.

LoCO: Can you explain that?

AM: No, I never went to HSU.

LoCO: Well why did you say —

AM: I’ve gone to College of the Redwoods.

LoCO: Right, but you said in this sworn declaration that you had gone to HSU.

AM: I’ve never gone to HSU.

LoCO: Then why did you say it in this declaration?

AM: I don’t remember stating that. I’ve only gone to McKinleyville High School, Trinidad Elementary, College of the Redwoods, Argus Pacific and a handful of other online courses.

LoCO: But do you remember making this sworn testimony?

AM: No.

LoCO: I have a copy of it here, if that helps. I mean, it’s got your signature on it. If you were involved in this hearing and signed the document, I’m not seeing where the identity theft — . Where did the ex-boyfriend take over your identity?

AM: In the employment with that company. You know, I did my internship with them to get my hours for my certification with Argus Pacific. Um … I was never employed by the company.

LoCO: They hired you as a contractor, correct?

AM: No, I did an internship with them for my Argus Pacific hours.

LoCO: OK. That’s not how it’s described in the court documents.

[Pause.]

AM: I, I don’t know. I mean … how do we, I mean, how do we … what do you want me to say?

LoCO: I’m just trying to get it straight here. I mean, in the transcript of the testimony from the hearing, they’re interviewing somebody who claims to be you in the presence of one of the owners of Kleen Environmental Technology.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: Did the owner not notice that the person testifying wasn’t you?

AM: Well, the owners of that particular company —. [Sigh.] I don’t want to get too far into this since it’s something that I could be held libelous for, but, you know, I was just there to do my hours. I was there to get my certification, uh, my handler certification, not to be part of any of their shenanigans, if you want to call it that.

LoCO: I’m just trying to get it straight because there are these court documents that say you were in the room testifying with the owner of a company that hired you.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: And you’re saying that somebody else was impersonating you at that time.

[Pause.]

AM: Mm-hmm, yeah. To some degree, the gentleman that I was dating at the time, yes.

LoCO: But why wouldn’t any of the attorneys, the owner of the company, the administrative law judge — why wouldn’t any of them notice that somebody was impersonating you?

AM: When you say, I mean, which attorney? I don’t know —

LoCO: Jim Sells is one attorney. Stephen B. Johnson is another one. Not only have they said you were in that room but they’ve looked at photos of you and said, “That’s the same person.”

AM: Okay.

LoCO: But you’re saying it was somebody significantly older pretending to be you.

AM: Yeah, it was my, it was my ex. The gentleman I was dating at the time.

LoCO: But I’m just, I don’t understand how the people in that room wouldn’t notice that somebody else had stepped into your shoes.

AM: It, I don’t think that it’s that somebody’s, I mean, the way that you’re saying it? It’s, it, yeah, it’s, it sounds awkward. But it’s —. I don’t know. I mean, I don’t know how far you want to go down this because — .

LoCO: I just — .

AM: My thing is I don’t want to go down this too far, then it’s going to be all about the gay guy running for county supervisor, and that’s the last thing I need in District One, right? So it’s, it …

LoCO: I don’t understand that connection.

AM: It’s like, how do I fully tell this story without getting into all the personal relationship [inaudible], my personal relationship with this gentleman, um. It’s like, even the lawsuit thing at St. Joe … .

LoCO: We don’t need to get into the personal relationship. I don’t need to know anything about the relationship. I’m trying to understand, within the context of this legal hearing … how did somebody impersonate you in that context?

AM: Well I guess you’d have to see the two of us together.

LoCO: You look similar?

AM: Yeah.

LoCO: Hm. … I’m finding it hard to believe, frankly.

AM: OK. I mean, I don’t know what else I can say to convince you. I, I, but this is my thing. I don’t know how much more we can prove to people, how many times a person can be fingerprinted, how many times a person can be vetted, background checked, all these different things. And yet continue to be questioned, berated and, you get what I’m saying?

LoCO: I do, and I’m not … by no means am I trying to berate you. I’m trying to understand the timeline here, the history of what happened, because they’re serious allegations, right? These are allegations that you committed perjury, essentially.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: I mean, the specific allegation was that you fabricated a letter from somebody who you had apparently met in the Crow Indian Tribe. I’m just trying to understand. I mean, the person who testified [as you] admitted to having been to this Crow Indian Tribe in Montana and meeting this Mr. Birdinground.

AM: Mm-hmm.

LoCO: Why would somebody steal your identity to go testify in [an administrative hearing]? I mean, if somebody was stealing your identity, what was he getting out of the deal.

AM: Well, I guess … a lot of money! My understanding is that there was a lot of money at play with this particular outfit getting their garbage permits they were trying to get. I mean, when you look at the amount of money that’s at play there with the profit margins that are published by people like Stericycle. I mean, just look at the amount of waste that we generate here in little old Humboldt County. It’s millions of dollars. Millions.

# # #

This back and forth went on for some time. McCloskey declined to identify his ex-boyfriend by name. Nor would he say which country he was from. He couldn’t explain why people recognized photos of him as the man who testified before the WUTC.

Nor could he explain how falsehoods, like his alleged degree from HSU, wound up in his sworn testimony to the WUTC. Nor how his boss, former Kleen owner Robert Olson, failed to notice that the man he’d hired had been replaced at some point by an imposter. Nor how brochures and a website with the name McCloskey Enterprises came to exist. Nor how a man who’d met McCloskey in Montana wound up with his name forged on a document in Washington.

At one point, as he was struggling to elucidate these mysteries, McCloskey glanced down at my iPhone, which had a voice-recorder app running onscreen, and mid-sentence he said, “I hate the fact that that thing’s on.”

In the days since the interview, McCloskey has not responded to emailed requests for the documents he said he’d forward, including a copy of the letter he allegedly sent to the BIA in 2013 and the “solid proof” his attorney had exonerating him of any misdeeds with the Scotts Valley Tribe.

Finally, on Monday afternoon, he responded to an inquiry sent via Facebook Messenger. “I did get your email. Unfortunately, I am busy dealing with family stuff. My grandfather is at UCSF having heart surgery and my Brother at home with hospice at his home in Mesa. There is a lot going on. I’ll get around to discussing your request with our committee sometime soon.”

In the meantime, he has unfriended me on Facebook.

Image from Allen McCloskey’s campaign website.

CLICK TO MANAGE