PG&E’s Humboldt Bay Generating Station in King Salmon. | Photos by Andrew Goff.

# # #

Last month, Pacific Gas & Electric preemptively shut off the power for nearly 2 million California residents in an unprecedented effort to reduce the wildfire risk posed by its own equipment. The major population centers of Humboldt County were not in the region where high winds and low humidity prompted the National Weather Service to issue a Red Flag Warning. And yet our power got shut off anyway.

Why? Well, the official word at the time was that the transmission lines supplying us power run through the danger zone and therefore had to be shut down. Later, at a hearing before the California Public Utilities Commission, a PG&E executive offered a slightly different explanation, saying the outage “should not have happened” here in Humboldt, but it did because one transmission line was down for maintenance just when other lines needed to be shut off for fire safety.

Regardless, the underlying question is why Humboldt County would need to rely on outside electricity at all when we have three local power plants capable of producing more than enough electricity to meet our power needs.

The most powerful is PG&E’s own plant in King Salmon, the Humboldt Bay Generating Station, which can produce enough electricity to supply about 125,000 homes. Humboldt County also has two biomass plants that burn wood waste, both of which sell power to the Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA).

Together these three plants can generate 197 megawatts of electricity, according to a May 2019 technical report from the California Independent System Operator, which oversees the high voltage transmission system.

That 197 megawatts is plenty. Humboldt’s peak demand — the time when the most people draw the absolute highest amount of power — is 180 megawatts, according to the RCEA, and demand is often far lower.

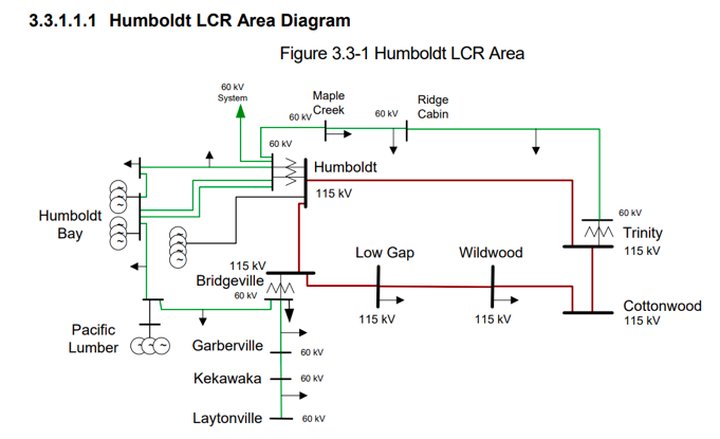

That same CAISO technical report includes a diagram that shows where and how electricity moves between Humboldt and regions to our east, which are served by higher-voltage transmission lines.

David Carter, managing research engineer at the Schatz Energy Research Center in Arcata, confirmed that disconnecting Humboldt from regions to our east would be a matter of flipping switches, either manually or remotely, at local substations.

Eliminating electricity flow on the 115 kilovolt lines that run east to west, and on the 60 kilovolt line that runs through Laytonville south to Santa Rosa, would leave Humboldt with a 60 kilovolt “local transmission backbone” that in theory could keep population centers electrified from Rio Dell north to Orick, Carter said.

Before the region could depend on that backbone, though, the sophisticated computers that now keep a bigger grid stable, constantly adjusting to fluctuating usage, accidents on power lines and much more, would have to be reprogrammed to account for the smaller system. The algorithms that control for countless contingencies already exist, but deciding which ones to use where requires a “coordination study” that could take six months to a year, Carter said.

Has PG&E already started that study, maybe as far back as July? The Outpost learned that the company was examining the challenges of operating in isolation from the larger grid since before then. However, PG&E spokespeople have proved to be remarkably evasive and obfuscating about their current capabilities, as you’ll see below.

We’re not the only ones asking questions. Last week, Humboldt County Board of Supervisors Chair Rex Bohn and Sheriff William Honsal sent a letter to PG&E executives asking why the utility didn’t develop a plan back in 2010, when the Humboldt Bay Generating Station came online, to isolate local customers on a dedicated grid, allowing the region to be energy self-sufficient when the need arises.

PG&E spokespeople have told the Outpost that it’s simply not possible. The Humboldt Bay Generating Station (HBGS), as it’s currently configured, can neither be started up, nor can it supply power to the local community, unless it’s connected to a fully energized grid. That’s what PG&E says.

However, documents obtained by the Outpost call those claims into question. Both internal PG&E reports and the utility’s communications with government agencies suggest that the HBGS, which has been in operation for less than a decade, was specifically designed to keep Humboldt County energy self-sufficient.

Just this past summer, PG&E asked for and received regulatory permission to operate in exactly the way spokespeople now say is impossible.

On July 1, in an email obtained through a California Public Records Act request, a local PG&E technician reached out to a pair of acquaintances at the North Coast Unified Air Quality Management District (NCUAQMD), the agency that monitors emissions from the local power plant.

“As you are aware,” wrote Ryan Messinger, the senior environmental field specialist at the HBGS, “due to the increasing risk of wildfire events, PG&E will likely be shutting off power to high-risk areas when conditions warrant.”

Messinger said it was unlikely that such power shutdowns would impact the Eureka area since the region is not in a high-risk area, but considering the “high impact potential” of getting blacked out, employees at the HBGS wanted to have a plan in place.

“When safety power shutdowns occur,” Messinger wrote, “HBGS would like to continue to provide power to the local community by generating power without being able to receive power from the statewide grid.” In the energy industry this is often called operating in “island mode.”

His concern was that, in firing up the power plant to restore power to the region, they might violate the conditions of their air quality permits.

Aerial view of the Humboldt Bay Generating Station showing the 10 dual-fuel engines. | Image via the manufacturer’s website.

The facility, built by Finnish manufacturing company Wärtsilä, consists of 10 16.3 megawatt quick-starting engines, each capable of running on natural gas or diesel. These state-of-the-art engines replaced a pair of 50-year-old steam boilers that predated the now-decommissioned nuclear reactor at the Humboldt Bay Power Plant.

The new facility is more efficient and releases about a third less greenhouse gasses than the old plant. However, as with car engines, which run dirtier when they’re driving around in traffic than when cruising on the freeway, the dual-fuel engines at the Humboldt Bay Generating Station produce more emissions if they’re running at less than half-power, or about 8 megawatts. So there are conditions in PG&E’s air quality permits saying the engines can’t run below 50 percent power for very long.

In his July 1 email, Messinger said that during a public safety power shutdown (PSPS), when the plant is isolated from the rest of the statewide electrical grid, chances are at least one engine will have to ramp up or down to absorb the fluctuating electricity demand in the region. The plant would also need to be be fired up with a diesel-powered emergency generator in a process called a black start.

Messinger wanted to make sure PG&E wouldn’t get in trouble for doing any of these things. “HBGS will not attempt to restore power locally without being confident that all permit conditions can be met in doing so,” he wrote.

Two weeks later, Al Steer, the compliance and enforcement manager at the North Coast Unified Air Quality Management District, wrote back saying it wouldn’t be a problem. (See that response here.) For regulatory purposes, he said, a PSPS would be considered an emergency, so any brief permit violations would be overlooked. In fact, his agency expected the plant to supply power to the local community during such an event.

“When PG&E proposed the current HBGS operation as presently permitted,” Steer wrote, “it was the District’s understanding that the plant was designed and intended to initiate and maintain operation both during loss of natural gas and power from the statewide grid … .”

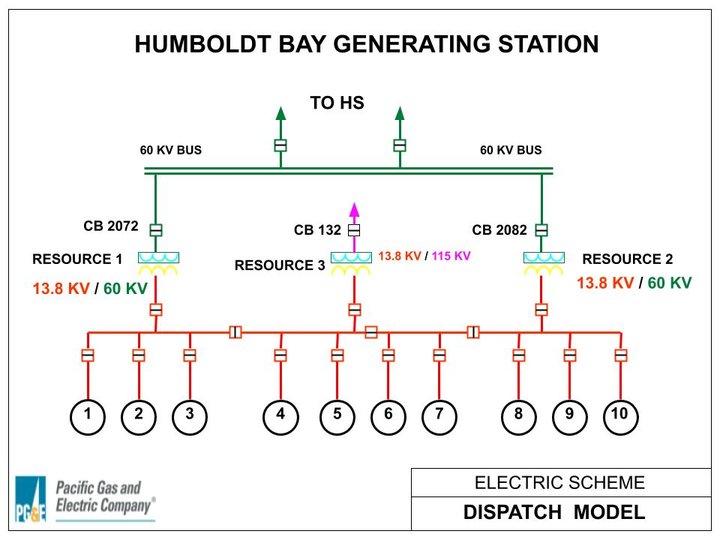

Diagram of the HBGS. For a more detailed “one-line diagram” of the plant, click here.

# # #

Last month, after the first of three PSPS events left local families and businesses with spoiled food, lost income and an abiding anger at PG&E, the Outpost reached out to the company’s local corporate spokesperson, Deanna Contreras, to ask why the Humboldt Bay Generating Station hadn’t been able to save us the trouble.

After all, we’d heard from the Humboldt County Office of Emergency Services just hours before the county went dark that PG&E was scrambling to prevent that from happening: “The utility is working on a solution to generate power locally at its King Salmon power plant that would help offset the effects of any shutoff,” the county said.

So why didn’t it work? In an Oct. 11 emailed response to Outpost Editor Hank Sims, Conteras said this:

I know you asked me this question a couple days ago but I’ve finally confirmed the situation with the Humboldt Bay Generation [sic] Station.

HBGS is not designed as a black start capable power plant, or said more simply, the plant does not have the capability to operate without being connected to a fully energized grid.

PG&E does have an engineering study underway to evaluate what plant modifications would be required to add that capability, including changes that may be required to the existing air permit to allow HBGS to operate over the range necessary when disconnected from the grid.

Basically, it’s not designed to operate separately from the grid.

Thank you,

Deanna

At the time, the Outpost had yet to obtain copies of PG&E’s July correspondence with the North Coast Unified Air Quality Management District, in which they discussed doing exactly that — operating separately from the grid — in some detail.

After obtaining those records from the NCUAQMD, we emailed the local PG&E employees who’d been involved in these discussions, including current plant manager Chuck Holm. They didn’t respond but instead forwarded the email to Contreras, who simply repeated her previous answer verbatim.

When pressed to explain the apparent contradiction she referred us to PG&E’s media hotline, which goes to the company’s San Francisco headquarters.

Last week the Outpost received emailed answers to our questions from PG&E’s top marketing and communications representative, Mark Mesesan. He maintained that the Humboldt Bay Generating Station “is not designed as a black start-capable power plant” and that it “does not have the capability to start-up without being connected to a fully energized grid.”

As for the evidence to the contrary in Messinger’s communication with the NCUAQMD, Mesesan argued that they weren’t actually discussing ways to “provide power to the local community” during a PSPS event, as Messinger clearly stated, but were instead concerned only with keeping the power plant itself intact.

“Operating in isolation or island mode means keeping HBGS in a ready state, using its emergency generator to supply the plant’s critical systems … ,” Mesesan said. “That is the issue being referenced in the NCUAQMD letter, as well as in Mr. Messinger’s emailed response – not our capability of starting-up the plant to feed electricity to the community during a PSPS event. Because, again, we currently do not have that capability.”

The Outpost then engaged in a frankly confounding email back-and-forth with Mr. Mesesan in hopes of clarifying. We thought maybe he just hadn’t looked closely at the documents we’d sent. Obviously PG&E has had its hands full responding to public outrage and criticism from state lawmakers and Governor Gavin Newsom, who say the bankrupt utility should be punished, broken up or even taken over by the state.

In an email sent Thursday we again quoted the key sentence from Messinger’s July 1 message to regulators:

HBGS would like to continue to provide power to the local community by generating power without being able to receive power from the statewide grid.

The meaning here is plain. “Mr. Messinger is clearly stating that his goal is to provide power to the local community, and yet you claim he’s only inquiring about powering the plant’s critical systems,” we wrote to Mesesan. As of publication time, he has yet to respond.

# # #

Meanwhile, the Outpost tracked down documents that challenge PG&E’s assertion that the Humboldt Bay Generating Station “is not designed as a black start-capable power plant.”

Here, for example, is a copy of the official operators log from August 2010, which shows that employees tested the black start capabilities of the Humboldt Bay Generating Station a month before the plant came online.

The entry for Aug. 29, 2010, at 3:26 a.m., reads, “BLACK START for Unit 4 — Successful.”

Forty-six minutes later: “BLACK START for Unit 5 — Successful.”

This capability was important to PG&E because it had an agreement with the California Independent Systems Operator, or CAISO, the independent nonprofit that oversees most of California’s bulk electric power system.

CAISO enlists a certain number of power plants across the state to maintain black start capabilities so it can meet the “emergency and preparedness operations reliability standard” set by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation.

The old Humboldt Bay Power Plant, with its steam boilers, was included in such an agreement, and PG&E wanted to keep that arrangement going with its new Humboldt Bay Generating Station.

In a June 2010 letter to CAISO, a copy of which can be found here, PG&E Vice President of Power Generation Randall S. Livingston boasted about the engines in the new plant.

“The HBGS units have both dual fuel capability and black start capability,” he explained.

CAISO wound up approving the request to swap out the old power plant for the new one in the black start agreement. Here is a chart from CAISO showing that the contract for “black start and dual fuel capability” at the Humboldt Bay Generating Station was extended into 2013.

However, that agreement is not in place anymore. Anne F. Gonzales, CAISO’s senior public information officer, told the Outpost via email, “PG&E removed HBGS from the black start agreement effective July 1, 2013.”

It’s not clear why PG&E chose to do this, but over the last decade or so the company has removed a number of resources from local operations and outsourced certain responsibilities to out-of-the-area workers, according to two former PG&E employees who worked at the Humboldt Bay Generating Station. They agreed to talk on the condition that they could remain anonymous.

One such change: PG&E used to employ transmission operators at the Humboldt Substation located off Mitchell Heights Road, east of Eureka, but now their duties are performed from a centralized electric distribution control center down south.

The former employees say this exporting of expertise may be the real reason why PG&E was unable or unwilling to operate the Humboldt Bay Generating Station in island mode during the recent power shutoffs. Black starting and operating in isolation from the larger grid are complex procedures, requiring technical know-how, sophisticated computer controls and coordination from workers at numerous points in the system.

With the current plant manager apparently unwilling to discuss these challenges, we’re left with explanations offered by PG&E spokespeople.

They say the generating station out at King Salmon is simply incapable of powering the local community during a shutdown — despite evidence that it was designed to do exactly that.

They say “multiple modifications to plant operating systems and our air permit” will be necessary — despite the fact that they received clearance from the air quality management district months ago.

They say they don’t know when the plant will be capable of black starting — despite operator logs showing that it’s had that capability all along.

PG&E says Californians can expect periodic power shutdowns to continue for the next 10 years. That’s not the only way the company is keeping us in the dark.

# # #

Carrie Peyton-Dahlberg contributed to this report. A former editor of the North Coast Journal, Peyton-Dahlberg covered energy for the Sacramento Bee from 1997 through the early 2000s.

CLICK TO MANAGE