It’s not that uncommon for a person to be elected to serve on the Eureka City Council with a minority of their constituents voting for them. The same goes for people running to be the city’s mayor. The rules state that any number of people can run for each office, and all you have to do to be elected is win more votes than any of the other people running against you.

There have been 30 separate elections for the mayorship and City Council since 2000. Ten of those races were between three or more candidates. Out of those ten, seven were won by a candidate who received less than 50 percent of the vote. Among them are current councilmember Leslie Castellano and current mayor Susan Seaman.

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

• MEASURE A: These Arcata High Seniors — and Their Supporters — Hope Arcata Property Owners Will Pay a Little Bit More to Keep the City’s Parks in the Green

• MEASURE D: South Bay Union School District Wants to Modernize its Campuses and Build a New Preschool

• MEASURE F: Arcata Fire District Again Proposes a Special Tax Increase to Help Fund Operations, But Some Say It’s Asking Too Much

In 2002, Peter La Vallee was elected mayor in a wild seven-way race after getting only 38.65 percent of the vote. Perhaps unsurprisingly, four years later he lost a reelection campaign – in a four-way race won by Virginia Bass, who got only 48.22 percent of the vote.

It’s jarring – or it should be jarring – that candidates for public office can win despite more people voting against them than voting for them. And yet that’s how we elect candidates for city office not only in Eureka, but in all Humboldt County and in most of the state of California. You don’t necessarily have to be a popular candidate to win, so long as the people who don’t want you to take office split their vote in two or three or four different ways.

This is the problem that Measure C, which the Eureka City Council is putting before voters in this election, is looking to solve. It would amend the city’s charter to institute ranked-choice voting – a system by which voters rank the candidates for city office in order of preference – first, second, third, etc. The point is to gauge the electorate’s true preference among a field of candidates, and also to allow people to run for public office without fear of splitting the vote between like-minded candidates. Proponents say it also leads to more positive campaigns; candidates will decline to attack each other, they say, because they’ll look to attract other candidates’ second-place votes.

But some people – even a few current city council candidates, if the recent League of Women Voters debate is any indication – say that the measure is confusing, or that ranked-choice voting itself is confusing, or they don’t trust the results from such a process. And they might have a point. The measure itself is a little vague, and the results from a ranked-choice election can be counterintuitive.

So what does Measure C do? What would a ranked-choice election look like?

###

The first thing to note about Measure C is that it doesn’t actually give the details of what the new voting system would look like. The measure amends the charter to allow for ranked-choice voting, and it directs the City Council to implement the details. That’s on purpose – amending the city charter is somewhat akin to amending the U.S. Constitution, in that it’s far more cumbersome than just passing a new or law.

“When you put detailed language in the charter, it makes it seriously difficult and expensive to change the smallest thing,” City Attorney Bob Black told the Outpost recently. If the City Council implements the new voting system, then a future city council can alter or tweak that system if it needs to – in response to changes in state law, say, or new technology.

(Incidentally, the only reason Eureka can implement a ranked-choice voting system independently of the state is that it has a charter. Like Fortuna, it is one of California’s 125 charter cities, which gives it greater latitude in some affairs, including how it conducts its elections for municipal office. All the other cities in the state are “general law” cities, which means they must follow statewide rules on these matters.)

Allowing the Council to implement the city’s new ranked-choice voting system may be expeditious, but it’s the first place where Measure C voters might protest that they don’t know exactly what they’re voting for. Though ranked-choice voting systems all share the same basic premise – voters are meant to rank the candidates from most preferred to least preferred – there is a whole bewildering galaxy of ways to tabulate the results: a contingent vote, a Borda count, a Condorcet method, etc. These methods are each “fair,” in their own way, but each can result in a different winner.

Though Black confirms that the council could, in fact, choose one of these more esoteric methods of tabulating the vote, it’s a pretty safe bet that the method they will choose to implement is the one known as “instant runoff voting,” or IRV. That’s the method used in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, San Leandro, the entire state of Maine and several other jurisdictions in the United States, and it’s the method described in the draft Eureka ordinance the city has up on its website in advance of the Measure C vote.

The way IRV tabulates the vote is pretty simple to explain. If a candidate gets a majority of first-place votes, that candidate wins. If no candidate gets a majority, the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated. Election officials then take all the ballots that had that last-place candidate as their first choice, and apportion those votes to the voters’ second choices. If any candidate has more than half the votes at that point, then the candidate is declared the winner. If not, the lowest candidate is again eliminated. And so on.

FairVote, a national ranked-choice voting advocacy organization, has a pretty good IRV explanatory video here:

The idea is that instant runoff voting is comparable to the normal, two-stage runoff voting that we’re already used to. When we vote for county supervisor, or for governor, or the state legislature, or for our Congressman, we vote in two rounds. In the spring primary election, we select from among a large slate of candidates. The two candidates who get the most votes then compete against each other in the fall general election. (For supervisor and other county offices, though, there is no runoff election if the candidate gets more than 50 percent in the primary.) Instant runoff voting is like that, advocates say, in that lower-ranking candidates are eliminated and higher-ranking candidates remain to compete against each other. It’s just that it happens in one election instead of two, saving everyone a lot of money and time.

But sometimes instant runoff chooses a different winner than a regular two-round runoff would choose. It’s entirely possible for a candidate who places third or fourth in first-place votes to walk away with the election – an outcome that would be sure to raise eyebrows were it to occur here.

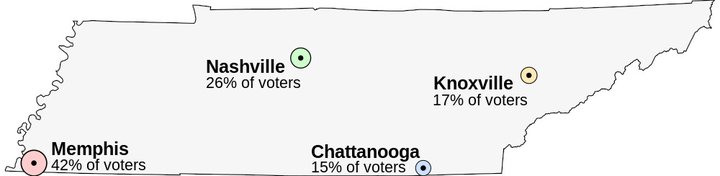

How is it possible? Wikipedia, which has robust information on various voting systems and their differences, likes to use a standard hypothetical example. Imagine that the state of Tennessee is choosing a new capital. Imagine, further, that the entire state population is centered around its four major cities — Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga and Knoxville – each of which is in the running to become the new capital. Finally, imagine that voters are entirely self-interested – they will rank their votes according to how near they are to the candidates:

Graphic: Wikipedia.

| 42% of voters (close to Memphis) |

26% of voters (close to Nashville) |

15% of voters (close to Chattanooga) |

17% of voters (close to Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

If you’re on your phone, you can scroll this table back and forth with your thumb to see it all. Table: Wikipedia.

Who wins this election?

If this were an election for Eureka City Council today — a plurality election — Memphis would win. More people voted for it than any other city.

If this were a two-round runoff election, like a vote for the county Board of Supervisors, Nashville would win. The two highest finishers in the first round — Memphis and Nashville — would move on to a runoff election. Chattanooga and Knoxville voters would vote for Nashville over Memphis.

If this were an IRV election, though? Knoxville would win. The last-place finisher, Chattanooga, would be removed from competition and its voters would be distributed to their second choice (Knoxville). That leaves Memphis with 42 percent of the vote, Knoxville with 32 percent and Nashville with 26 percent. No city yet has a majority, so the new low vote-getter (Nashville) is eliminated. Nashville voters’ second-place choice (Chattanooga) is already out, so those voters are distributed to their third choice, Knoxville.

Knoxville now has 58 percent of the vote and Memphis 42 percent. Under instant runoff voting, Knoxville is the winner, despite being the first or second choice of only 32 percent of the population. (Nashville, meanwhile, was the first or second choice of 68 percent of the voters.)

It’s a hypothetical example, of course — in real life, it’s doubtful that everyone in each city would vote exactly like all their neighbors — but it shows, in theory, how instant runoff voting can lead to unpredictable, non-intuitive and possibly controversial outcomes.

###

In a recent conversation with the Outpost, Caroline Griffith, chair of the North Coast People’s Alliance, one of the local organizations backing Measure C, held that these kinds of potential outcomes — in which a third-place finisher vaults into first place as ranked-choice votes are tallied — shouldn’t be disturbing. They represent one measure of a community consensus.

“In that particular sort of case, the end result will be that that person, though they may have not gotten all the first-place votes, appealed to the largest number of people,” Griffith said.

Even more importantly, though, to Griffith and the numerous local other organizations and individuals supporting the measure — among them labor unions, progressive groups and the League of Women Voters — is the argument that ranked-choice voting does away with the innately non-democratic system of electing candidates with minority support, while also opening up the city’s government to more voices.

“I know that conversations happen to discourage people from running for office for fear that they will split the vote, which is another thing that really rankles me, personally, and a lot of other people,” Griffith said. “That also really doesn’t feel democratic. This is a way that anyone who feels compelled to serve in public office can throw their hat in the ring and do it.”

CLICK TO MANAGE