Visual simulation of Nordic Aquafarms’ planned land-based fish farm, a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) facility planned for the Samoa Peninsula. | Image via Humboldt County’s Draft Environmental Impact Report.

###

The public has until Friday to review and comment on the county’s draft environmental impact report (DEIR) on the big land-based fish farm that Nordic Aquafarms plans to build on the Samoa Peninsula. The report is about 1,800 pages long, so if you’re planning to read the whole thing and haven’t yet started, best of luck!

Fortunately, local leaders of nonprofit environmental organizations have been poring over the voluminous document since it dropped on December 20, and in interviews they say they appreciate how open the Norway-based company has been to feedback and project revisions — including the decision to conduct a full environmental impact report — but they have a number of serious concerns, including the project’s massive energy demands, the effects of effluent discharged offshore, impacts to wildlife from water intakes in Humboldt Bay and more.

The DEIR, prepared for the county by engineering firm GHD, concludes that, with mitigation measures, the project will have no significant environmental impacts. That’s the same conclusion reached in the initial study released last April. But environmental stakeholders argue that this finding is based on insufficient baseline data and analysis.

None we spoke to said they’re outright opposed to the project, for which Nordic plans to spend millions of dollars further remediating the Humboldt Bay Harbor District’s blighted former pulp mill property on the peninsula. But they’re asking for some modifications and commitments in hopes of lessening the fish farm’s environmental impacts.

To review, Nordic has proposed building the world’s largest land-based recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), a state-of-the-art facility with a 17.6-acre footprint producing tons and tons of Atlantic salmon. They’d be raised from eggs to the juvenile stage in a hatchery facility at the center of the five-building campus, then transported via underground pipes to two massive grow-out modules, where they’d swim against a steady current while growing to market size.

Simulation of a Recirculating Aquaculture System from a Nordic Aquafarms video. | via GIPHY

###

With a projected annual production capacity of up to 27,000 metric tons of fish, the plant is designed to supply West Coast markets from Seattle to Los Angeles. (The company wants to build a similar facility in Belfast, Maine, to supply East Coast markets.) The Samoa facility, which would operate 24/7, is projected to employ 90-100 employees during Phase 1 of the two-phased buildout and up to 150 under Phase 2.

Two existing sea chests on Harbor District docks would pull in 10 million gallons of Humboldt Bay saltwater per day, and two million daily gallons of freshwater would be supplied by the Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District. Twelve and a half million gallons of effluent would be discharged daily through an existing mile-and-a-half-long ocean outfall pipe, which pulp mill owners were forced to install after being sued by the Surfrider Foundation and the EPA in the late 1980s.

According to the DEIR, onsite water treatment plants “will subject all inlet and wastewater to a stringent treatment process, including fine filtration, biological treatment and ultraviolet sterilization.”

If anyone was looking for a reason to doubt the strict veracity of the DEIR, the authors seem to have inadvertently provided one: Deep in the report, on page 53 of Appendix D (Marine Resources), former GHD senior scientist Ken Mierzwa is listed as one of four preparers. Trouble is, he says he was not involved.

In a Feb. 3 email commenting on the DEIR, Mierzwa says he did not contribute to Appendix D or any other part of the report.

“Without going into detail, I wish to make it clear that I disagree with a number of the statements made in the results and conclusions of Appendix D and carried forward into the EIR,” he writes. “Many items require additional analysis and/or additional mitigation, and I would have refused to put my name on the document as written had I known that it existed.”

Asked to respond, Nordic’s executive vice president of commercial operations, Marianne Naess, forwarded a statement from GHD:

Ken Mierzwa did not contribute to the Marine Resources Biological Evaluation Report associated with the Nordic Aquafarms EIR. Including Ken’s name as an author was an administrative oversight. Mr. Mierzwa’s name will be removed from the report and documented through the California Environmental Quality Act process.

We reached out to Mierzwa and asked him to elaborate on his perspective on the DEIR’s shortcomings. Below is a rundown of some of the major concerns raised by Mierzwa and others, including a local fisherman and a variety of environmental stakeholders.

Energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions

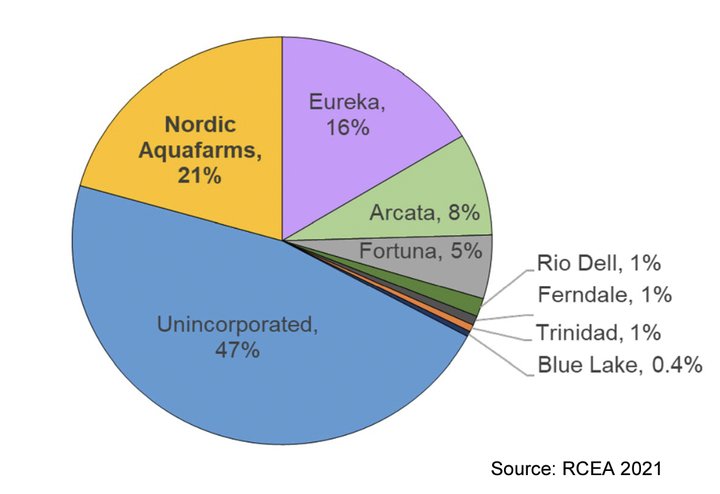

The DEIR says the project’s anticipated annual electricity usage at full build-out is 195 gigawatt hours (GWh). That’s a difficult statistic for most laypeople to comprehend, but a pie chart in the report’s energy chapter puts the figure into perspective. It shows that the facility would use roughly as much energy as the cities of Eureka and Fortuna combined:

Annual electricity usage at full build-out (circa 2030) as a fraction of current total county load. | From the DEIR.

“It is a shocking amount of electricity,” said Tom Wheeler, executive director of the Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC).

Caroline Griffith, executive director of the Northcoast Environmental Center (NEC), agreed, calling this energy demand “pretty mind-blowing.”

“It gives an indication of just how impactful this project could be and how important it is that the county accurately analyzes and assesses those impacts,” she said in an email.

EPIC, NEC and others have asked Nordic to commit to using 100 percent renewable energy from Day One. The company hasn’t gone quite that far, but it has committed to using “non-carbon” energy by following the procurement policies of Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA), the joint powers authority that administers Humboldt County’s Community Choice Energy program.

Nordic also plans to incorporate roughly 15 acres of rooftop solar panels, enough to produce about 4.8 megawatts of electricity. The company says it would like to tap into any “larger or more beneficial carbon-neutral energy project [that] becomes available … such as the 4.6 gigawatt offshore wind project proposed approximately 21 miles offshore of Humboldt Bay.”

That project is still in the planning stages, and Wheeler said that while he appreciates Nordic’s stated desire to run as cleanly as possible, the county’s current energy infrastructure limits just how green the plant can be.

Humboldt County has limited import/export capacity, so while RCEA may purchase 100 percent renewable energy on the open market, most of the electricity Humboldt County customers actually use enters the grid via PG&E’s Humboldt Bay Generating Station, a 163-megawatt facility in King Salmon that runs on natural gas with propane backup.

“If we were to be connected to the grid in a different way I think that I could accept [Nordic’s projected] amount of electricity,” Wheeler said.

By purchasing the power through RCEA, Nordic will be “greening the larger grid,” he said, “but if we don’t have enough renewable energy [accessible locally] to serve this project, I think we are doing a disservice to our climate.”

EPIC plans to ask the company to commit to purchasing renewable power — locally, when it becomes available — as a means of driving investment. “I think that the way we’re most comfortable with this project moving forward is with offshore wind as well,” Wheeler said.

Nordic has argued that despite its eyebrow-raising energy requirements, their facility on the Samoa peninsula will actually reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. That’s because U.S. residents consume more than four times the amount of salmon we harvest, importing the vast majority of it from Europe and Latin America — a carbon-intensive journey.

Daniel Chandler, who sits on the steering committee of 350 Humboldt, a nonprofit dedicated to reducing emissions from fossil fuels, said he’s not sure exactly how well the comparison pencils out. For one thing, much of the fish currently being exported from Norway comes to the U.S. via ocean liner rather than airplane, though Nordic often uses the latter in its emissions analyses. For another, fish grown in Nordic’s Samoa facility would still need to be trucked to markets up and down the West Coast.

“That’s not analyzed in the EIR but it ought to be,” Mierzwa said.

Colin Fiske, executive director of the Coalition for Responsible Transportation Priorities, said he also has issues with the report’s greenhouse gas emissions analysis. The report bases its projections on PG&E’s self-reported 2019 figures for carbon dioxide emissions per megawatt hour, and he believes the data from 2019 was anomalously, maybe even absurdly low.

These data “allowed them to conclude — we still think erroneously — that they had a less-than-significant impact on climate emissions where, if they had used other data, it would have been clearly significant,” Fiske said.

He also believes the report’s authors used the wrong carbon emissions threshold from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District.

“There’s two different ones: a ‘stationary source threshold’ and a ‘land-use threshold,’” he said. The former is the one cited in the report, but Fiske said that’s supposed to apply only to facilities that produce their own emissions, like a factory or power plant.

Another potential source of emissions is the fish feed.

“It’s not discussed in the DEIR at all,” said Chandler. “There’s just no mention of greenhouse gas emissions from fish food.”

The environmental sustainability from fish food production has improved a lot in the past 20 years, he noted, explaining that is used to take about 10 pounds of other to produce one pound of salmon. That figure has dropped to a worldwide average of 1.87 pounds thanks to increased use of vegetable protein oil, insects and other ingredients, Chandler said.

Nordic has said it will source “the best available fish feed” with a goal of minimizing marine ingredients while meeting the health and welfare needs of the fish.

“We will only source our feed from accredited facilities that meet the criteria of ASC (Aquaculture Stewardship Council) or Global Gab certifications, just as we have done for our ASC- and Global Gab-certified facilities in Denmark and Norway,” Naess said in an emailed statement.

Still, Chandler would like the company to commit to buying food that has been tracked for greenhouse gas emissions and has the lowest level possible. Wheeler also identified the fish feed as an area of concern and said he’d like to see Nordic “lean in” and leverage their position as a market leader to drive innovation and further increase the amount of vegetable and insect content in fish feed.

Chandler is also worried about the use of chemical refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons, which have thousands of times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide.

In responding to emailed questions from the Outpost, Naess referred more than once back to the analysis in the DEIR, saying full answers “might require much more detailed responses than would be possible to comment in a newspaper article.”

But she also noted that all comments submitted during this public review period will be addressed in detail, as required by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), and the formal responses will be included in the Final Environmental Impact Report.

Regarding Fiske’s analysis of PG&E’s self-reported emissions she said, “Nordic used figures from 2016 in the first model in the IS/MND [Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration]. This was updated in the analysis in the EIR, using the more recent 2019 calculation/figures,” which she said are “the latest available third party verified data.”

She continued:

Nordic shares the concern with regards to GHG [greenhouse gasses] and has therefore committed to follow RCEA´s goals with regards to non-carbon and renewable energy. This is clearly stated in the EIR and will be a binding condition in the Coastal Development Permit. The GHG levels in the EIR therefore reflects the actual emission levels.

Nordic’s local project manager, Scott Thompson, and executive vice president of commercial operations, Marianne Naess. | File photo by Andrew Goff.

Outfall discharge

Like others who’ve examined Nordic’s plans, Humboldt Baykeeper Executive Director Jennifer Kalt was struck by the sheer size of the facility.

“It’s a huge project,” she said. “I mean, it’s massive, and it’s really got a lot of people worried that the nutrient levels — nitrogen in particular — could exacerbate the algae problems.”

She was referring to the effluent that will be pumped into the ocean via the 1.5-mile discharge pipe. This is the same pipe that Louisiana-Pacific once used to dump millions of gallons of untreated wastewater per day into the Pacific Ocean.

Nobody we spoke with thinks Nordic’s much-lower amount of treated discharge will be as harmful to marine life, but Kalt and others still worry that the effluent’s higher temperature and perennial discharge of nutrients such as nitrogen could stimulate algae growth, exacerbating the existing scourge of harmful algal blooms.

In response to feedback from environmental groups, Nordic last year agreed to independent monitoring of the effluent once the project is online, but Kalt and others take issue with GHD’s methods of collecting baseline data, saying the measurements used in the DEIR’s modeling were taken near the mouth of Humboldt Bay rather than offshore where the effluent will actually flow.

“They think the data they use from inside Humboldt Bay is just fine,” Kalt said. “They’re using logic and rationale that makes sense to someone that doesn’t know the science. They’re saying the bay flushes [into the ocean] so the it’s probably similar [conditions]. Well, it’s not.”

Delia Bense-Kang, Northern California coordinator for the Surfrider Foundation, agreed, saying the two locations have potentially different temperatures, salinity and other conditions.

The DEIR concludes that the environmental effects of the discharge will be less than significant. This was the area of the study for which Mierzwa was erroneously listed as a preparer, and he told the Outpost that he finds the level of analysis insufficient.

“I don’t think there’s enough information to make those sweeping [conclusions] that there’s no need to mitigate,” he said.

Asked about these issues, Naess replied, “Before we make any further comments, we would need to see the specific concerns in detail to be able to address them sufficiently. This will be addressed in detail in the reply to comments in the CEQA process.”

Photos of the Harbor District’s existing infrastructure via the DEIR.

Bay intakes

Jake McMaster, a local commercial fisherman, said he’s also worried that the outfall pipe may cause harmful algal blooms, and he’s also concerned about the sea chests sucking up millions of gallons of water from the bay.

“Humboldt Bay is a giant estuary with all sorts of juvenile everything — juvenile smelt, salmon, crab. Have you ever seen a juvenile crab?” he asked. “They’re tiny, like tadpoles.” McMaster is worried about the potential for these little critters to get sucked up into or against the intake screens.

The permit for the bay intakes is being pursued not by Nordic but rather by the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District. The local government agency owns the sea chests along with the rest of Redwood Marine Terminal II, having acquired the former pulp mill property in 2013 for a single dollar.

The California Coastal Commission and California Department of Fish and Wildlife will have their say on that permit, but Nordic’s DEIR addresses the infrastructure, too, noting that the sea chests will be retrofitted and modernized to meet applicable design criteria. This includes the installation of fine-mesh screens to prevent impingement and entrainment of sea life.

Mierzwa said this is another area where he feels the analysis falls short. Specifically, he brought up Section 316(b) of the Clean Water Act, which requires the EPA to issue regulations on the design and operation of intake structures.

This particular section of law has been litigated extensively, Mierzwa said, adding that it’s taken very seriously. “There’s essentially no mention of it in Appendix D in this EIR,” he said. “It needed more analysis than it was given.”

The Harbor District has begun conducting studies to analyze the impacts of these intakes.

Naess said in an email, “This is addressed in detail in the EIR and the permit application from the Harbor District.” She noted that the screens will have a mesh size of one millimeter.

Transportation

At full production, the Nordic facility is expected to add 205 daily automobile trips, according to the DEIR. It would also add 32 outgoing trucks each week carrying waste to secondary use processing sites. Deliveries, including fish feed, shipping materials and process chemicals, would add another 20 truck trips per week.

The DEIR concludes that the increased traffic will have no significant environmental impact, but Fiske takes issue with the baseline figures, noting that the report compares its projections to the county’s per capita driving habits.

“And when you look at the entire county, of course, the average is way high because of people who live way out in the rural areas,” Fiske said. “And so that leads them to consistently conclude that there is no significant impact.”

Naess responded to this by saying, “Nordic believes we used the appropriate data and methodology for this study. Specific comments will be addressed as part of the CEQA process.”

Nordic executives led a group made up primarily of representatives from local environmental groups on a tour of the former pulp mill property last July. | File photo by Andrew Goff.

‘It’s just humongous’

Several of the people we interviewed kept returning to the project’s size.

“This is one of the biggest projects we’ve seen in the county for a long time,” Griffith observed. “There is a need to have the right information to make a correct assessment about the impacts, and I don’t know that we necessarily have all the right information.”

That said, she added that it would be great to see the site cleaned up. “That is part of what is in people’s minds: This site will eventually be used for something. We’d like to see it used in the best possible way.”

Kalt said she and others have encouraged Nordic to start smaller and then scale up when conditions warrant. “It’s just humongous,” she said of the existing plans. “We keep telling them, ‘If you make it smaller to start with, then we can see what the impacts are.’ The company has no track record of doing anything like this.”

Naess took issue with this allegation.

“The technology is NOT untested,” she wrote in her email. A company acquired by Nordic has spent decades designing RAS facilities that are currently in operation, and Nordic has such farms of its own, “which is more than any other RAS company,” Naess said.

“As stated before, the facility consists of several ‘independent units,’ none of which are larger than the farms that we are currently operating and it will be the same size as our fully permitted Maine facility,” she continued. “The facility will also be built in two phases, which allows for Nordic to commission, operate and adjust the facility to local conditions (if necessary) before building the second half of the facility.”

Like Griffith, Kalt said she’s not necessarily opposed to it going forward. “It’s not a project that I think can’t be mitigated,” she said. “But they need to do a better analysis.”

Wheeler said this project is up there with the rejected Terra-Gen wind farm as the biggest developments proposed during his time in Humboldt.

“I think that our approach for this project has been different, because in many respects [Nordic] has been open to criticism,” he said. “They’ve been willing to listen, propose changes to the project and work with the community. I hope this continues. We’re at a really important stage here, and they’ve done well by us so far.”

The company has listened to stakeholder concerns and, in some cases, altered the project to accommodate them — “the completion of the full EIR being one of those examples,” Wheeler said. “I think the benefit of the full EIR is being shown in the kind of concerns we are now raising. We’ve been able to present more nuanced issues and drive a conversation that is better for all of us in the county.”

Naess expressed a similar sentiment:

Nordic appreciates the good dialog we have had with the environmental groups during the permitting process. They play an important role as watchdogs to protect the environment in Humboldt and have rightfully challenged the project to make it better.

Nordic listened to the environmental groups and the community and did an EIR. Nordic listened to the concerns voiced by the environmental groups and included additional monitoring. Mutual respect and collaboration is always the way to create win-win solutions and improve the outcome. Nordic wants to thank the environmental groups for their willingness to be a constructive player in this process.

Once again, you have until Friday to submit your own comments on the project. They can be sent to the Humboldt County Planning and Building Department at 3015 H Street in Eureka or via email: CEQAResponses@co.humboldt.ca.us.

###

CORRECTION: This post has been corrected to reflect that Griffith works for the NEC rather than Friends of the Eel River. The Outpost regrets the error.

PREVIOUSLY:

- Nordic Aquafarms Plans to Grow Atlantic Salmon in Land-Based Fish Farm on Former Pulp Mill Property

- County Declares No Significant Environmental Impact for Proposed Samoa Fish Farm; Will Receive Comments, Critiques Through May 24

- In a Surprise Move, Nordic Aquafarms Agrees to Conduct Full Environmental Impact Report for Its Land-Based Fish Farm on the Samoa Peninsula

- Local Environmental Groups Laud Nordic Aquafarms’ Decision to Complete a Full Environmental Impact Report

- (PHOTOS) Nordic Aquafarms Execs Lead Tour of the Corroding Remains of the Pulp Mill Property Where They Plan to Build a Big Land-Based Fish Farm

- PENINSULA RISING: County Creating a Financing District to Supercharge Development in and Around Samoa

- (VIDEO) Take a Virtual Tour, With a Brief History, of Nordic Aquafarm’ Proposed Peninsula Project Site

- County Releases Draft Environmental Impact Report for Nordic Aquafarms’ Fish Factory Project on the Samoa Peninsula

CLICK TO MANAGE