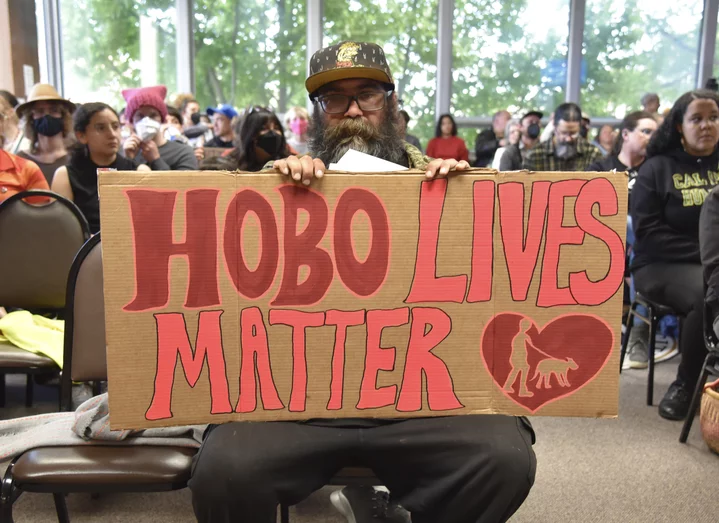

Dozens gathered outside Eureka City Hall on Tuesday to protest a controversial ordinance that would target people in encampments. The man in this photo asked, “Do you want a picture of a pissed off homeless guy?” | Photos: Isabella Vanderheiden

###

Eureka’s controversial homeless encampment ordinance is dead.

Following three-and-a-half hours of public comment at another marathon Eureka City Council meeting, the council voted 3-2, with Councilmembers Scott Bauer and Kati Moulton dissenting, to deny an ordinance that would have increased penalties for some people living in unauthorized homeless encampments, and upgraded certain crimes from infractions to misdemeanors.

The now-discarded ordinance — linked here — was a streamlined version of two existing city policies that restrict unlawful camping, sitting, lying and loitering in public spaces. The proposal sought to redirect offenders to community-based rehabilitative services, rather than jail, through the city’s Law Enforcement Alternative Diversion (LEAD) program. Penalties could have resulted in one year in jail or a fine of up to $1,000.

In the months since it was first presented to the council, the ordinance has drawn sharp criticism from homeless advocates and allies who argued that the “police-centered” ordinance would cause undue harm to unhoused community members and create additional barriers to housing and supportive services. Supporters of the ordinance hoped it would have the opposite effect by steering people struggling with substance abuse off the street and into treatment.

A little bit of background: The city council took its first look at the consolidated ordinance during a grueling seven-and-a-half-hour meeting on March 18 that included hours of impassioned public testimony. At that meeting, the council directed staff to form a working group with local stakeholders and people with lived experience, incorporate their feedback into the ordinance and bring it back for discussion sometime in the near future.

The modified ordinance was brought back sooner than expected at the urging of Bauer, who, at the council’s April 15 meeting, expressed concern that the council would continue to “kick the can … down a long and apparently endless road.”

Ahead of last night’s meeting, a large crowd gathered at Eureka City Hall to protest the ordinance, wielding signs that called for “TRUST NOT TICKETS” and “HOUSING NOT HANDCUFFS,” among others. The crowd was greeted by several police officers as people filtered into City Hall and ascended the stairs to council chambers on the second floor, where several other police officers were chatting. Humboldt Bay Fire Chief Tim Citro helped folks find seating and directed people to the overflow viewing room when all the seats were taken.

More than 100 people packed into council chambers at Eureka City Hall.

Speaking via Zoom, Eureka City Manager Miles Slattery presented the changes to the draft ordinance, which clarify certain aspects of the LEAD program. The modified ordinance includes additional reporting requirements and notes that the LEAD program would be administered by mental health and social work professionals, not law enforcement.

“The LEAD program is limited to 10 active participants and 10 individuals on the waitlist at any given time,” Slattery explained. “When capacity is reached, LEAD staff will communicate with EPD staff, sergeant, or their designee to temporarily suspend referrals and enforcement of this ordinance except in outstanding or exigent circumstances. … The goal of LEAD is to intervene before involvement with any judicial system, whether it’s an attorney, a judge or a courtroom.”

Slattery emphasized that the ordinance would target problematic individuals, not everyone living in encampments. “[This is] a tool to address those community members — a very small population of community members [who] are not accepting those services — and to help them to realize that what they’re doing is not good for themselves or the community.”

“According to who?” someone shouted from the audience, prompting Mayor Kim Bergel to ask attendees to be respectful and wait for their opportunity to speak. Several times throughout the meeting, the audience drowned out city officials in mid-sentence with boos and jeers, laughing when Slattery underscored the importance of taking a compassionate approach to addressing homelessness.

Slattery provided an overview of city-led programs and services, adding that the city has helped rehouse 230 people in the last five years. The city recently opened the Crowley Site, a long-awaited transitional housing project on Hilfiker Lane, that will supply 33 modular housing units with shared restrooms, kitchens and laundry facilities to people living in encampments in the greenbelt along the Hikshari’ Trail.

“We have the property manager on-site, and we’re starting to enroll tenants in there five at a time,” Slattery said. “We’ll continue to enroll until we’re at capacity. As we’ve discussed previously, we’ve been establishing a waiting list for folks along that trail segment who are on that waiting list, and they’ll start being enrolled into the program.”

The city is also working with Betty Chinn to relocate Betty’s Blue Angel Village from its current location on Washington Street to a larger property to facilitate another 40 units, doubling capacity.

“The Betty Kwan Chinn Foundation is receiving a donation to replace the containers that are there on site,” Slattery said. “Relocating those to another location would allow for 40 more of the housing first principle, very low-barrier space for individuals.”

At the end of his presentation, Slattery shared two accounts of anonymous individuals with particularly pervasive encampments and a history of violent behavior who he believed could have benefited from the LEAD program. He also read letters submitted by Chinn and Bryan Hall, director of the Eureka Rescue Mission, both of whom expressed support for the ordinance.

“We needed to help [the unhoused community], work with them and support them in getting a better quality of life,” Chinn’s letter stated. “I really trust this proposal and believe that it is needed now. When I need help, when I need someone, when I need a professional to show up, the CARE team shows up; that’s what I need. … I really hope that people support this.”

In his letter, Hall recounts his own experience with recovery, noting that his arrest was “the best thing that ever happened” to him.

“I want to be clear, I’m not in support of punishing anyone who is struggling,” Hall wrote. “Many of the people who are living on the streets outside our facility are unwilling to come inside. It’s not because there’s no room, it’s because we have standards. … While this may seem like a hard line to some, it is one we hold because we believe in healing, not enabling. We believe that recovery starts with accountability.”

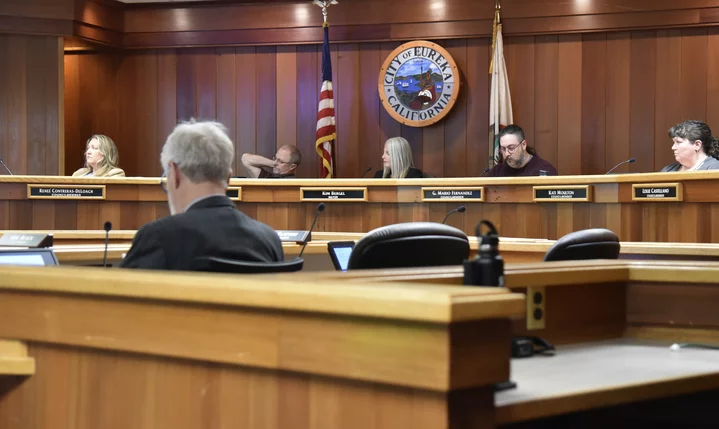

The Eureka City Council.

‘I’m not comfortable with it being so vague.’

Turning to questions from the council, Councilmember G. Mario Fernandez asked a series of questions about existing programs and future plans to increase shelter space and access to services in Eureka. Responding to a question about the ratio of outreach workers to unhoused people, Slattery said the city’s Uplift team has two full-time homeless outreach workers and four part-time workers, which drew laughter from the crowd.

“There are other workers that are out there doing this,” Slattery continued. “We guesstimate that about 80 percent of the population that is unsheltered participate in the dining facility program, so a good portion of their time is concentrated there, as well as out in the field and where they’re at. There is a Point-in-Time count … that guesstimates that there are 600 unsheltered individuals [in Eureka]. I can assure you that there’s not 600 unsheltered individuals. We do surveys every two years with an actual meet and greet, face to face with those under sheltered individuals, and they’ve ranged anywhere between 180 and a little over 220.”

“That’s because they’re hiding,” someone shouted from the audience.

During a particularly testy exchange, Fernandez asked Slattery to explain how the city’s public spaces are unsafe and how the community would benefit from the ordinance. Slattery pointed to the anonymous account of John Doe that he had shared “clearly demonstrates that the amount of assaults going on down there is unsafe.” Fernandez pushed back, asking why John Doe wasn’t arrested.

“Because there weren’t people, as I stated in the memo, who were willing to file charges. When these things happen and somebody’s hit with a metal bar and somebody’s arm gets broken, that person whose arm got broken wasn’t willing to press charges,” Slattery said, adding that one of the local volunteer trail steward groups no longer provides clean-up services out of safety concerns. “Whether it’s a perception or reality … or whether it’s just uncleanliness, they don’t feel safe.”

Fernandez noted there are “other public nuisance laws in place regarding smell, taste, etc,” and asked why, if the pervasive issue is violence, the ordinance is focused on homeless encampments rather than enforcement and reporting. “How does camping get rid of John Doe?”

“Because we can remove him … from the area where he’s causing the problem,” Slattery said, emphasizing again that many of the people living in the encampment near St. Vincent de Paul’s dining facility are reluctant to report violence to the police. “The idea would be, look, dude, you can’t be here anymore, and we’re going to arrest you under this [ordinance] — and not for violence, because nobody’s going to file charges against you — and remove him from the area that he’s causing that problem.”

Councilmember Renee Contreras-DeLoach sought clarity on what qualifies as “outstanding or exigent circumstances” in which someone would be admitted to the LEAD program when it’s at capacity. EPD Chief Brian Stephens said “exigent circumstances” referred to “anything that threatens public safety” and requires an immediate response from law enforcement.

“It can be an issue on the trail where we have an encampment that is creating a safety issue, where we get complaints that people are being threatened, or something that doesn’t quite fit or fall into probable cause for a crime but it’s unsafe for folks to use the trail,” Stephens continued. “That’s something we need to address immediately because of the number of complaints we’re getting. We can use [the ordinance] at that point, based on the discretion of the sergeant, to resolve that public safety issue.”

Contreras-DeLoach said she could understand the spirit of his sentiment, but felt the ordinance should include clearer language.

“In order to enforce something, it has to [have] clarity, and it doesn’t seem that there is a real fine point on what’s going to be considered,” she said. “It’s going to be something that is interpreted there in the moment of what they consider it, and I’m not comfortable with it being so vague.”

Chief Stephens attempted to explain further, noting differences between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law. While the letter of the law may state that it is illegal to jaywalk and anyone who does so is subject to a ticket, police officers rarely do so, and most often let people off with a warning, he said.

Contreras-DeLoach also asked how the ordinance and LEAD Program would benefit people. Chief Stephens emphasized that the hope is to get people into assistance programs and “where we want them to be, and that’s not in jail.”

“It’s not that the charge goes forward and they’re automatically going to either face the fine or jail time,” he continued. “There are other options through probation … it just comes from a different avenue, which we have no control over. That’s the issue with sending [these cases] to the district attorney’s office versus dealing with it in-house is we lose that control over those resources when it goes to the district attorney’s office.”

At one point in the discussion, Councilmember Leslie Castellano said she was stuck on “the idea that we are creating or reestablishing a misdemeanor in order to address a problem in the DA’s office with prosecuting other existing crimes,” and asked if the city was working with the county on solutions.

Slattery emphasized again that the “main impetus” behind the ordinance was to give staff a tool to deal with problematic encampments and violent individuals.

Jacob Rosen, the city’s managing mental health clinician, added that the LEAD program is meant to prevent someone from being referred to the DA’s in the first place.

“By implementing the pre-bookings diversion or pre-arrest diversion, we’re able to bypass that whole system,” he said. “A positive impact of that is that it would relieve some of the impact on the DA. However, this gives us the ability to work with clients directly, and it’s a better quality of care. … We can go straight from enforcement contact and create another referral source.”

‘Please don’t do this to us.’

As the council wrapped up its questions ahead of the public comment period, Fernandez asked for “clarity and understanding” about the city-issued press release sent out last week that announced public comment on the ordinance would be limited to three hours. He asked whether the call was issued by Mayor Bergel, noting that the council had not weighed in on the item. She confirmed that she made the call.

“Then, with that being the case, I would like to appeal the decision of the mayor,” Fernandez said, promptly making a motion to that effect, which was seconded by Contreras-DeLoach.

Moulton asked for a quick head count on attendees, which was roughly 230 people, including those on Zoom. “So, that is 11-and-a-half hours if everybody gets three minutes,” she said. “We’ve heard eight hours of public comment on this issue before … and we need to get into the actual process.”

After a bit of additional discussion, the council voted 3-2, with Bauer and Moulton dissenting, to toss the three-hour limit, which drew applause from the crowd.

However, some members of the council weren’t thrilled at the prospect of 11 hours of public comment, including Castellano, who said she had to be in Sacramento at noon the following day. She made a motion to allow for four and a half hours of public comment, which was seconded by Bauer. The motion passed 4-1, with Fernandez dissenting.

Contreras-DeLoach floated the idea of restricting each speaker to one minute so everyone would have an opportunity to speak, which was seconded by Bauer. The motion passed 4-1, with Fernandez dissenting.

The vast majority of speakers at last night’s meeting urged the council to deny the ordinance on the basis that it would criminalize homelessness.

One man, who only identified himself as Ray, said he’s been homeless for 25 years and is newly sober. He called on the council to deny the ordinance and offer more compassion to people living on the streets.

“You know, the hardest part about that is finding people who are willing to look at me like I was a person … and not have people look at me like I was an animal,” he said, adding that some of the local shelters are too selective in their admission process. “Sometimes they’re kicking people out for small things … and I know some people just don’t want to have to deal with certain rules or guidelines, but they just want to be accepted into a shower or bathroom.”

“If you sit and talk with some of them, a lot of times they have a coherent conversation with you,” he continued. “Why? Because you addressed them as a human. … You just took that moment to say, ‘Hello, how you doing?’ and actually mean it.”

Another woman named Crystal described her experience living in an encampment and asked the council to have empathy for people who “can’t walk the line” in the way society expects them to.

“Maybe someone’s got a broken foot or someone’s got some twitches or whatever. We can’t all walk the same line,” she said. “We should not put everybody in the same basket and try to condemn us for just one or two people that are having a hard time, who don’t know how to express themselves in public or to people. Please, don’t do this to us. … Just help us. Don’t condemn us [or] put us in jail. Just help us.”

Dozens of other speakers echoed the same sentiment, calling for the council to provide sanctioned camping and increase access to public bathrooms and showers, not increased enforcement that could put vulnerable people at risk.

Public comment wrapped up as the meeting approach the five-and-a-half-hour mark. Castellano quickly made a motion to deny the ordinance, which was simultaneously seconded by Contreras-DeLoach and Fernandez.

Before voting on the item, Castellano read aloud a pre-written statement detailing her reflections on the ordinance and her “deep responsibility to the community.”

“I’m voting no on this position because I believe that we are capable of changing the systems that we participate in,” she said. “For what other reason would I, an artist and community organizer, have run for office and been elected by the people of Eureka? … I want to acknowledge the work of staff in bringing this item before us for consideration. I recognize and intend to do something to change people’s lives, but I think that this strategy will erode the trust that is needed to build long-lasting change while only having limited successes.”

In his closing statement, Fernandez said he still couldn’t identify the compassionate element of the ordinance, adding that it is incongruent with previous actions of the council, including its decision to declare Eureka a Sanctuary City.

“Given that our laws are often [intended] to ensure public safety and mitigate and deter behavior, I challenge the necessity and belief that this ordinance deters the behavior of camping, given that the behavior isn’t generally out of wanton disregard or malfeasance,” he said. “Rather, it comes from economic conditions. Homelessness isn’t a behavior, it’s an environmental and social condition that can’t be easily regulated with fines in jail.”

Contreras-DeLoach said she, too, had experienced homelessness in her life, and felt that the proposed ordinance would inadvertently “target status, not conduct.”

“I swore that if I was ever in any kind of position of power, I would defend the weak,” she said. “I’ve also been homeless. I grew up in poverty. I’m not impoverished now, and I spend my resources and my time trying to help other people. … My commitment extends through to this, and that’s why I’ve made my decision.”

Moulton emphasized the importance of holding people accountable for their actions, but felt the ordinance itself should never have been presented to the council.

“This is a bad ordinance. It needs to be rewritten, but it is not a completely useless tool,” she said. “This ordinance was not ready for publication, and it shouldn’t have ever been published in this condition. It is far too broad for what staff brought us. … It would make it illegal to, as many of you have said, sit on a blanket in a park and eat a picnic with your friends. … It should have had accountability written into it, not for the folks experiencing homelessness, but for the people making the judgment decisions about who would or would not be put into this system.”

Bauer echoed Moulton’s statement and acknowledged the lack of trust in the authority. Still, he felt something should be done.

“This ordinance isn’t perfect, but it was something,” he said. “I still think we should do something, and I hope that we can all learn to trust each other in the future and trust our government, because there’s a lot lack of trust with our federal government.”

The council voted 3-2, with Bauer and Moulton dissenting, to deny the ordinance.

Reached for additional comment about what happens next, City Clerk Pam Powell confirmed that the “ordinance is dead,” adding that the council did not provide direction to work on it in the future.

CLICK TO MANAGE