(AUDIO) Get Your Dead On With Humboldt County’s Own ‘Dead On’

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, March 12, 2025 @ 11:11 a.m. / On the Air

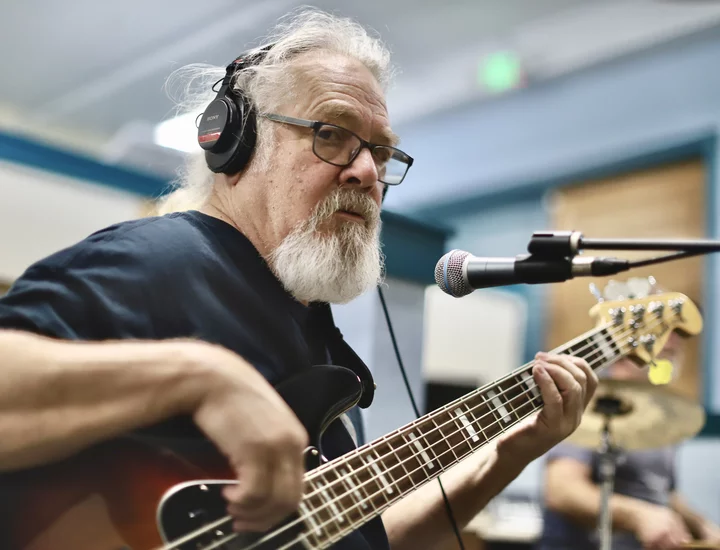

Dead On in Old Town

Just statistically speaking, if you are reading this we are going to go ahead and assume that you yourself are in a Grateful Dead tribute band. We play the odds over here.

But the chances are significantly less that you are in a Grateful Dead cover band that recently had the honor of playing on The Point’s Live at Five with Chuck Rogers. That prestige has only been bestowed upon Humboldt’s own Dead On who stopped by the KWPT studios in Old Town to share a couple tunes over the airwaves.

For posterity, we have archived that performance here, along with a few pictures from the day.

Marty Dodd

Nick Moore

Norman Bradford

Rick DeVol

KWPT’s Chuck Rogers

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 17 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 6

CHP REPORTS

4593 Mm299 E Tri 45.90 (RD office): Report of Fire

ELSEWHERE

100% Humboldt, with Scott Hammond: #107. Jan Friedrichsen: Veteran Rescuer Explains How Search Dogs Track, Find, And Bring People Home

RHBB: Crash Blocks Lane on Northbound U.S. 101 at Humboldt Hill Onramp

RHBB: Crash off 101 into Trees North of Willits

Study Finds: When Moths Freeze: How LED Streetlights Are Silencing the Night

Yurok Tribe Mourns the Loss of Young California Condor Found Dead in Redwood National Park; Cause of Death Determined to be Lead Poisoning

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, March 12, 2025 @ 9:46 a.m. / Tribes , Wildlife

Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ (I am friend or kind or good natured) was found dead in January. | Photo: Yurok Tribe

###

Press release from the Yurok Tribe:

In January, Northern California Condor Restoration Program (NCCRP) condor B7, Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ (I am friend or kind or good natured) was found dead in the remote backcountry of Redwood National Park. His passing marks the first loss of a condor from the Northern California population under the NCCRP. At roughly 18 months of age, he was the youngest condor in the flock and had been in the wild for just over three months.

The NCCRP delayed a formal announcement until the official cause of death was determined. The results from a pathology examination indicate the cause of death to be lead poisoning. Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ was found to have a lead air gun pellet in his ventriculus, or gizzard, and high to very high concentrations of lead in his liver and bone. The source of the pellet is unknown.

“The loss of Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ was a huge blow to us. Death is part of work with wild animals, but his was hard as our first loss” said Program Manager and Yurok Tribe Senior Biologist Chris West. “Thankfully, we have 17 other amazing birds in our flock carrying our hopes, dreams, and prayers.”“A natural death would have been less painful for us, the humans watching as he started to flourish in the wild. Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ was known for his friendliness, preening and huddling together with other condors, sharing food easily. He had only been flying free for a few months. That he was brought down by something human caused and preventable is devastating,” said Yurok Tribe Wildlife Department Director Tiana Williams-Claussen.

Lead is the single biggest threat to condors in the wild and is responsible for nearly half of released condor mortalities where the cause of death is determined. Almost all poisonings are linked to carrion from lead-shot game, livestock, and vermin. A tiny lead bullet fragment is enough to kill not only a condor but also vultures and eagles, should they scavenge on remains of an animal killed with lead ammunition. These important scavengers remove carcasses from the landscape and are critical in reducing the spread of disease in many game species.

Pey-noh-pey-o-wok’ was one of 18 free-flying condors released by the Northern California Condor Restoration Program (NCCRP) over the last several years. In 2022, the NCCRP released the first condors to fly over ancestral Yurok territory in more than a century. The program plans to release the next condor cohort later this year.

To learn more about the Yurok Tribe’s condor restoration work visit www.yuroktribe.org/yurok-condor-restoration-program .###

The California Condor Recovery Program is a multi-entity effort, led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service working to establish self-sustaining condor populations within the historical range. The program includes addressing threats to the species in the wild; captive breeding; and reintroduction at field sites, like the Northern California Condor Restoration Program. In addition, the program raises awareness about condors and how the public can help support them through individual actions, like making the switch to lead-free ammunition.

They Live in California’s Republican Districts. They Feel Betrayed by Looming Health Care Cuts

Kristen Hwang / Wednesday, March 12, 2025 @ 7:43 a.m. / Sacramento

Pharmacy tech Natalie Padilla in front of the SEIU-UHW Union office in Bakersfield on March 11, 2025. Padilla’s family relies on Medicaid, motivating her to travel to Washington, D.C. to speak with Rep. David Valadao’s staff about the health insurance program. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Natalie Padilla signed up for Medicaid 17 years ago. She had just given birth and needed insurance to bring her son to the doctor. The Bakersfield resident was still in school, and her husband’s work didn’t offer insurance. She was on the program for six months.

About an hour north of Bakersfield, Rodolfo Morales-Ayon, a 21-year-old community college student, relies on Medicaid today. He’s studying political science and wants to go to law school. Morales-Ayon grew up in Pixley, a small Central Valley town where air quality is poor and asthma and respiratory infections are common.

Farther south in Orange County, Josephine Rios’ 7-year-old grandson has cerebral palsy and needs Medicaid to pay for his medication and specialized wheelchair, which cost $22,000. Elijah is a lively boy, Rios said, but his disability means he’ll likely need Medicaid for his entire life.

All three live in areas of California where their Republican representatives recently voted on a federal budget bill that would all but guarantee cuts to the Medicaid insurance program, which is known in California as Medi-Cal.

Although the details will take months to iron out, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office released a report last week indicating that it was impossible for House Republicans to meet their goal of eliminating $880 billion in spending over the next 10 years from the committee that oversees Medicaid and Medicare without cutting from either of the social safety net programs. Medicaid provides health insurance for disabled and low-income people. Medicare insures seniors over 65.

The Senate voted on a narrower budget bill that is less likely to hit Medicaid, but the chamber will have to come to an agreement with the House later in the year. President Donald Trump has praised both budget bills, while at the same time indicating he doesn’t want to cut safety net programs for the poor. Congress is also rushing to avert a government shutdown Friday with a separate budget bill.

“Medicare, Medicaid — none of that stuff is going to be touched,” Trump said in a February interview with Sean Hannity on Fox News.

But Republican lawmakers want a deal that would offset the cost of extending Trump’s first-term tax cuts that are set to expire at the end of this year, and Medicaid represents the largest share of federal funding to states.

California’s behemoth Medicaid program insures 14.9 million people, more than one-third of the state’s population. Republicans hold nine House seats in California and represent 2.5 million Medicaid enrollees. All nine voted to approve the House GOP budget bill at the end of February.

Some of the state’s most conservative areas benefit disproportionately from Medicaid, including Rep. Jay Obernolte’s district in San Bernardino County’s high desert and Rep. Doug LaMalfa’s district in the far northern counties, where 48% and 43% of the population have Medicaid respectively.

Other Republicans represent swing districts where voting against Medicaid could be risky politically. Rep. David Valadao in the San Joaquin Valley represents the greatest share of Medicaid enrollees in the state at 67%. He voted to advance the House bill. Six years ago, his vote to eliminate the Affordable Care Act likely cost his reelection for a term.

In contrast, California’s Democratic state lawmakers have taken every opportunity to expand the Medicaid program, which grants full-scope health coverage to low-income people (for instance: an individual making less than $20,783 or a family of four making less than $43,056 annually).

The number of people with Medicaid in California has increased 31% since 2014 when the Affordable Care Act allowed states to enroll people who made slightly more than the federal poverty threshold. California has also expanded in other categories, using about $8 billion annually of state money to insure undocumented immigrants.

Today, the state spends $161 billion on Medicaid, the majority of which comes from the federal government.

Republicans have focused talks on rooting out “waste” and “fraud” in federal programs, but early proposals appear to aim at the fundamental payment structure of Medicaid. Experts say those types of cuts may require states to pay more for the programs, putting the political and financial onus on state lawmakers.

“Many of these proposals are about having states be left holding the bag,” said Edwin Park, a public policy research professor at Georgetown University. “If states have less funding available, then it’s impossible for them to sustain their current levels of spending.”

‘Some people will die without it’

In a statement on the House floor following the initial budget vote, Valadao said extending Trump’s 2017 tax cuts would make a real difference for “working families, farmers, and small business owners” but acknowledged that many of his constituents need Medicaid.

“I’ve heard from countless constituents who tell me the only way they can afford health care is through programs like Medicaid,” Valadao said that day, indicating he could vote differently later in the year on a final proposal. “And I will not support a final reconciliation bill that risks leaving them behind.”

But some California voters still feel like their representatives have failed them by advancing a bill that will likely lead to Medicaid cuts.

Rudolpho Morales-Ayon, a community college student, in Pixley Park in Pixley on March 4, 2025. Morales enrolled in Medicaid as a child and continues the health insurance program. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

“For our representative David Valadao, this is a betrayal. It’s nothing less than that,” Morales-Ayon, a district voter, said. Morales-Ayon voted for Valadao’s Democratic opponent last fall.

Morales-Ayon had Medicaid as a child because his parents’ jobs didn’t provide insurance. Per capita earnings in Valadao’s district are about half as much as statewide earnings, according to census data.

“People need these resources to manage their day-to-day lives,” Morales-Ayon said.

Padilla, who also lives in Valadao’s district, now works as a pharmacy technician at Mercy Hospital Southwest in Bakersfield. She traveled with her union to Washington, D.C. several weeks ago to try and make an appeal to Valadao not to vote for any Medicaid cuts. Staff told the group that he was too busy to see them, Padilla said.

Padilla grew up in the district and said multiple family members, including cousins and her 84-year-old grandmother, have Medicaid. Her family who rely on Medicaid have low-paying or part time jobs that don’t offer health insurance. Any reductions in coverage would be “devastating,” she said.

“This is the raw, honest truth of hardworking people,” Padilla said.

In Orange County, Rios, a certified nursing assistant for Kaiser Permanente, voted and rallied for Republican Rep. Young Kim, but these days she’s consumed by the thought of what will happen if Medicaid is cut. She’s worried that she’ll lose her job and that patients will lose access to health care.

Most importantly to her, Rios said, her grandson Elijah with cerebral palsy might lose insurance. Elijah’s cerebral palsy medication costs $5,000 each month, she said.

“It’s not a Republican thing. It’s not a Democratic thing. Forget the political BS, this is a human thing,” Rios said. “Some people will die without it. Some people’s lives like my grandson’s are at risk without it.”

Josephine Rios’ 7-year-old grandson, Elijah, needs Medicaid to manage his cerebral palsy, the certified nursing assistant from Orange County said. Photo courtesy of Josephine Rios

Rios, who has worked in health care for more than two decades, said she voted for Kim because Kim spoke compassionately about her constituents during her election campaign and also supported health care workers. But the budget vote was a “slap in the face.”

“I’m very disappointed and very frustrated that she voted and she didn’t fight harder to keep Medi-Cal uncapped not only for her constituents like myself but for the young children who need it,” Rios said. “She needs to remember why we elected her into office.”

In a statement on her website, Kim joined other Congressional Republicans in emphasizing that the bill passed was procedural and didn’t make cuts to any specific programs. The vote simply allowed the GOP to “move the ball forward,” Kim said in the statement.

“As this process moves forward, I will continue to make clear that a budget that does not protect vital Medicaid services for the most vulnerable, provide tax relief for small businesses, and address the cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions will not receive my vote,” Kim said in the statement.

In her district, which covers portions of Orange County and the Inland Empire, 21% of people use Medicaid.

An ‘existential threat’ to health clinics

But some health care providers say even the procedural vote was “too risky” for their liking.

“It is an existential threat from our perspective,” said Francisco Silva, chief executive of the California Primary Care Association, which represents more than 1,200 community health centers in California.

Community health centers, also known as federally qualified health centers, serve predominantly low-income communities. In some areas of the state, Medicaid is the only reason why health centers and hospitals can piece together enough revenue to stay open, Silva said.

Marisol De La Vega Cardoso said any Medicaid cuts risk destabilizing community health centers at a time when poverty is increasing. De La Vega Cardoso is a senior vice president at Family HealthCare Network, the second-largest community health center network in the country.

“Unfortunately we might be forced to cut back on services that are so needed,” De La Vega Cardoso said.

Dr. Richard Thorp, a longtime internal medicine specialist in Paradise, is very concerned about how Medicaid cuts may destabilize the workforce in an area that already struggles to recruit doctors. Republican LaMalfa has represented by Republican LaMalfa since 2013.

The once idyllic town in the Sierra Nevada foothills outside of Chico was the site of California’s deadliest wildfire in 2018, which also destroyed the local hospital. More than 80% of the population never returned to live in Paradise, and Thorp’s medical group dropped from 15 primary care doctors to one full-time doctor supported by four advanced practice staff.

“We have significant manpower and pipeline issues,” Thorp said. “As you make these cuts it makes it less and less feasible to practice in Butte county.”

LaMalfa said in a statement online that the House budget bill was a first step in “reining in Washington’s out-of-control spending” and that a “typical family in NorCal” would see taxes go up without the federal government cutting spending. The statement made no mention of Medicaid.

“It’s time to prioritize policies that grow the economy, cut waste, and ensure a stronger financial future for the American people.”

###

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

OBITUARY: Elsa I. Cline, 1941-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, March 12, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Elsa I. Cline passed away at home in Eureka on March 8, 2025 at the age of 84. She

was born in Kalajoki, Finland in 1941 and immigrated to the United States with her

family in 1949. Elsa and her family called Eureka home for all of her adult years. This is

where she met and fell in love with Dennis Cline. This year they would have been

married 57 years. They were blessed with three children and have lived a life full of

family and good memories.

Elsa worked for Humboldt County Social Services for 21 years before retiring at age 70. She was an active member of Cutten Community Church for many years before becoming ill. She was also an active member of the local Finn Club and celebrated her Finnish Heritage and would often find her in an apron serving rice pudding during the Scandinavian festival.

She was proceeded in death by her parents, Johan Henrikki Lankila and Vilhelmina Tavasti Lankila. Her brothers Pentti and Martti and his wife Saara of Finland. Sister Tyyne M. Pittman and her husband Stanley Pittman. Beloved mother and father-in-law Homer and Dorothy Cline and grandchild Samantha M. Prosser and Samanthas father Jerry Prosser.

She is survived by her husband Dennis G. Cline. Daughter Deborah Kindley and her husband Tim of Fortuna. Daughter Jennifer Cline. Son Jeffrey Cline both of Eureka, Her grandchildren Vanessa and Erik Masad of Oregon, Lynda and Eddy Noggle and Josh Jackson of Eureka. Brandon Brown. Great grandchildren Logan Kindley, Logan Masad, Conner Noggle and Aaron Noggle. Brother, Jack and his wife Esperanza of Vacaville and their children and grandchildren. Brother Ben & Jeannie Lankila of McKinleyville and their children and grandchildren. Younger sister Helen and Jim Johnson of Idaho and their children and grandchildren. She is also survived by her cousins, Vaino Lankila and his wife Sirpa and children in Finland, Hilja Davis and her family in Oregon.

Elsa lived a simple but full life. She never met someone she didn’t like and had a kind word for everyone. She was ill for five years as her dementia continued to progress. It was hard to see her become such a shadow of herself. This is a terrible disease and one we would not wish on anyone. It strips you of the person you once were and the memories you shared and leaves you a shell of who you were. Please remember her as she was full of life and love. She would like us to remind everyone to live life to the fullest, make memories and be kind. In lieu of flowers make donations to your favorite local charities or Food for People.

Funeral services handled by Sanders Funeral Home. A chapel service will be held at Ocean View Cemetery on Friday, March 14th at 3 p.m.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Elsa Cline’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

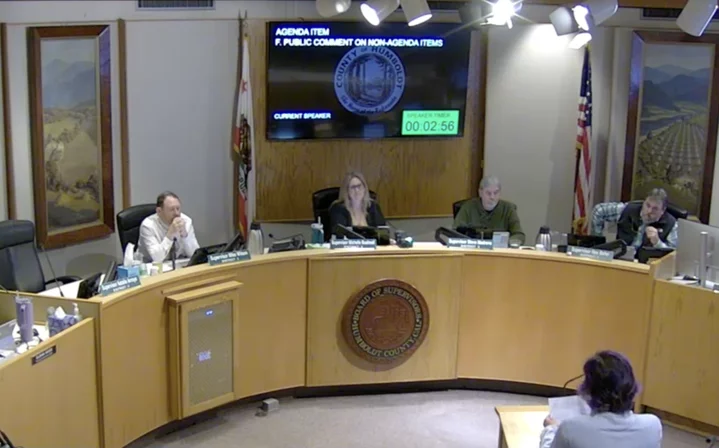

TODAY in SUPES: Board Revokes 21 Cannabis Permits for Failure to Pay Taxes, Tweaks Short-Term Rental Ordinance and Allows Honsal to Hire New Employees

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, March 11, 2025 @ 4:17 p.m. / Local Government

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors (from left): Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson, Second District Supervisor and board Chair Michelle Bushnell, Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone and First District Supervisor Rex Bohn. Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo attended the meeting remotely via Zoom. | Screenshot.

###

After years of offering local weed farmers metaphorical carrots, the Humboldt County Supervisors today brought out the stick, unanimously agreeing to revoke 21 cannabis cultivation permits issued to growers who have failed to pay their Measure S taxes.

Planning and Building Director John Ford explained that the 22 growers listed in the staff report have had more than a year to enter into a payment plan for their delinquent taxes and have failed to do so. All of their state licenses have expired or been revoked.

“This group of 22 did not even put in the effort to enter into a payment plan,” Ford said. “So, essentially, they have been in violation of the board’s direction, county ordinance [and] the requirements of their permit since March 31 of 2024.”

One of the 22 came in to the Planning and Building Department after getting notice of this pending revocation and paid a little over half of the $2,181.60 in fees owed to the department, so the board elected not to revoke that permit, leaving it suspended for the time being. (The owner has not cultivated anything on the property, Ford said.)

Anyone expecting gnashing of teeth or rending of garments from struggling weed farmers would have been disappointed. None of the permit holders in question showed up or called in to protest, and the revocations went quickly.

One grower who’s slated to have his permit revoked later this month was in attendance. He said that times have been tough for years, but this past year has been particularly difficult for locals in the legal market.

Sheriff Billy Honsal spoke in favor of the revocations, saying, “This board and our county has bent over backwards to try and bring people into compliance with the law. Sometimes you have to draw the line, and this is the line.”

He added that revoking these permits also serves to reward the people who are following all the rules and paying what they owe.

“And unfortunately, not all cannabis farmers are going to survive,” Honsal said.

Short-Term Rental Ordinance Tweaks

Earlier in the meeting, the board considered adopting some amendments to county zoning regulations governing short-term rentals such as Airbnbs. Ford introduced the matter by saying these amendments, which were already approved by the Humboldt County Planning Commission, are simple adjustments that address unintended consequences of the existing ordinance.

However, the matter prompted a substantive debate and split vote among the supervisors.

One of the proposed changes involved road conditions. The current language requires permitted short-term rentals to be on road built to a Category 3 standard, as defined in county code.

“There’s a problem with that,” Ford said. “Not many roads in all of Humboldt County are built to a Category 3 standard.”

He explained that the purpose of that language was simply to assure that the roads could handle the functional capacity of Category 3 roads, so staff recommended changing the language to say, “the access road shall operate at a functional equivalent of a Category 3 road.”

Another proposed change, requested in response to a real situation, involved changing the method for calculating neighborhood concentration of short-term rentals. The existing language of the ordinance requires “a separation of 10 lots as the crow flies” between permitted short-term rentals.

Ford used a PowerPoint slide to show on a map of McKinleyville neighborhoods that measuring distance “as the crow flies” created a much larger radius than was intended — large enough, in fact, to stretch from one neighborhood into another one entirely. Staff recommended changing the standard to a radius of 300 feet, measured from the center of the lot where each rental is located.

The most controversial proposal involved allowing short-term rentals on land zoned Agriculture General, or “AG.” Despite the implications of that zone name, Ford explained that many applications for short-term rentals have come from owners of fairly small parcels in AG zones where there is no agricultural use taking place, making them ineligible to qualify as a farm stay opportunity. (Farm stays are encouraged and thus more lightly regulated by the county.)

Staff proposed changing the ordinance to allow short-term rentals on AG parcels of less than five acres. Parcels between five and 10 acres would require a special permit while parcels larger than 10 acres would still require their rentals to be associated with a farm stay.

Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson voiced concern for preserving both housing and agricultural land, and he argued that allowing short-term rentals on such land would make it even less viable for producing agriculture, in part by potentially impacting neighboring parcels.

Wilson suggested requiring a special permit for all AG-zoned parcels of less than 10 acres but more than 2.5 acres while allowing home shares short-term rentals on parcels of 2.5 acres or smaller and allowing home share rentals on AG-zoned parcels of less than five 5 acres.

He also suggested measuring the concentration radius at 600 feet from the center of each parcel, rather than 300, to prevent mass conversion of neighborhoods into rental properties.

Second District Supervisor and board Chair Michelle Bushnell objected to these suggestions. She said there are many five-acre parcels in the Carlotta-Hydesville area that are classified as AG despite being residential in nature. And she objected to charging such property owners $2,500 for a special permit.

“I don’t feel okay about charging someone $2,500 when there isn’t an issue around that short-term rental; it qualifies in every other way,” she said.

First District Supervisor Rex Bohn advocated for less regulation in this arena due to low demand during this difficult economic period when property owners may need the income.

“I called a couple people that have numerous rental units — by numerous I mean quite a few — and their vacancy rate is twice as much as usual … ,” he said. “We do a pretty good job of shooting ourselves in the foot and over-regulating everything.”

Bushnell reiterated that she would not vote in favor of Wilson’s suggestion to require a special permit for short-term rentals on AG-zone parcels larger than 2.5 acres. She felt that’s too restrictive.

“I’m not going to vote on the 2.5 acres because there’s just too many parcels within my district that are the five-acre minimums,” Bushnell.

Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone said he’s concerned about housing being converted to rental properties, saying he’s not inclined to make that easier.

Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo, who attended the meeting remotely via Zoom, agreed that it’s important to preserve housing for community members and ag lands for agriculture, though she also understands the needs of people “transitioning right now” — out of the cannabis industry, one assumes — who need to find new ways to make money from their properties.

Bushnell argued that parcels of five acres or smaller are simply not big enough to support agriculture activity — not in the current state of the weed industry.

“I just really hope we consider that,” she said.

Wilson countered by noting that everything the board was considering, with regard to this ordinance, constitutes an expansion of entitlements, changes that allow property owners more opportunities. He made a motion to adopt staff’s proposed changes with his own suggested provisions — allowing short-term rentals on AG-zoned parcels of 2.5 acres or smaller without a special permit; allowing them on AG-zoned parcels between 2.5 and 10 acres with a special permit; allowing home shares on AG-zoned parcels of five acres or less; and changing the neighborhood density radius from 10 houses “as the crow flies” to 600 feet.

Madrone seconded the motion, and after a bit more discussion, the board passed the motion with a vote of 3-2, with Bushnell and Bohn dissenting.

Honsal Gets Exemptions From County Hiring Freeze

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office wants to hire a public information specialist and a property technician, and so today’s board agenda included a request from that department for an exemption from the county’s ongoing hiring freeze, implemented nearly three years ago in response to a massive budget deficit, which persists to this day.

The request was on the consent calendar, slated to be passed alongside of slate of other items, without any specific deliberations, but Wilson asked to pull the matter for discussion. He said the county may soon find itself unable to afford the employees it already has, so hiring new ones deserves scrutiny.

Sheriff Honsal said both positions are essential to his office. The public information specialist will replace the current employee in that position, who’s leaving at the end of the month. Her replacement will be responsible for writing press releases and social media posts, plus coordinating responses to requests made under the California Public Records Act and the Freedom of Information Act.

“And let me just tell you what a feat that is,” Honsal said. “That is something that’s that we actually need more help on. … If we miss a timeline, we’re opening ourselves up [to] liability when it comes to responding to public records [requests].”

The public information officer will also be responsible for producing public information videos in the aftermath of any “critical” incidents, such as police-involved shootings.

The property technician, meanwhile, helps to maintain security and control in receiving, storing, releasing and disposing of evidence and property under the department’s control. And Honsal said the position’s costs will be about 80 percent covered via $56,000 generated by the multi-agency Humboldt County Drug Task Force.

“These are budgeted positions, we have the money for them, and this is essential,” Honsal said.

Wilson asked how many public information officers the Sheriff’s Office has now, recalling a pair of new hires last year — via another exemption to the hiring freeze — as part of an anti-human trafficking campaign financed by the Howard G. Buffet Foundation.

Honsal said those positions function separate from the office’s day-to-day operations.

Bushnell spoke to the importance of having a PIO, especially for local volunteer fire departments.

Madrone reiterated the difficult fiscal position the county finds itself in.

“If we don’t start reining in our budget, we’re talking about spending money we don’t have, literally, which puts the county in debt,” he said, “not just using our reserves, but starts putting us in debt.”

Arroyo said that the board is trusting each county department head to articulate their reasoning for exemptions to the hiring freeze, “because you’re the expert in your department.” She added that the same discernment will be required when it’s time to make the difficult decisions.

“I will be trusting you as the expert to determine where those cuts need to be made,” Arroyo said.

The board approved Honsal’s request unanimously.

You Will Soon Have a Chance to Own One of Eight Horses and Burros That Once Roamed Free Across America’s Public Lands, Making Nuisances of Themselves

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 11, 2025 @ 2:46 p.m. / Animals

Those were the days. Photo: BLM.

Press release from the Bureau of Land Management:

Saturday, March 15, at the Humboldt County Fairgrounds in Ferndale. The BLM will offer four halter-trained fillies and four burros that have not been trained.

Anyone interested can preview the horses and burros when they arrive at the fairgrounds at about 4 p.m., Friday, March 14. Adoptions on a first-come, first-served basis begin at 8 a.m. Saturday and continue until 4 p.m. The adoption fee is $125 per animal.

The animals are certified to be healthy and vaccinated against all common equine diseases. Adopters must be at least 18 years old and have facilities that meet the BLM’s requirements. The adoption event is being held as part of the Back Country Horsemen of California Redwood Unit’s Trail Obstacle Challenge event.

The BLM is responsible under the Wild Free Roaming Horses and Burros Act for protecting and managing wild horses and burros on public lands. The agency periodically removes animals from the range when populations exceed levels established to allow wild horse and burro herds to thrive in balance with other range users, including wildlife and permitted livestock. These animals are then available for adoption at events throughout the country. Visit the BLM’s wild horse and burro program online for more information.

Mass Layoffs at Companies Working on Humboldt Offshore Wind Projects; At Least Some Local People Laid Off

Isabella Vanderheiden / Tuesday, March 11, 2025 @ 1:45 p.m. / Offshore Wind

A 9.5-megawatt floating wind turbine deployed at the Kincardine Offshore Wind project, located off the coast of Aberdeen, Scotland. Photo courtesy of Principle Power.

###

The future of Humboldt County’s offshore wind industry appears increasingly uncertain following mass layoffs at RWE and Vineyard Offshore, the multinational energy companies leading efforts to develop commercial-scale floating wind farms on the North Coast. The job cuts come in response to widespread market uncertainty following President Donald Trump’s efforts to ban offshore wind development in the United States.

In a regulatory filing submitted last week, RWE Offshore Wind Services, LLC confirmed its plans to cut dozens of jobs in its U.S. offshore wind division. Reached via email this morning, RWE spokesperson Ryan Ferguson told the Outpost that the company has laid off “close to 100 people,” including some California-based employees working on the Canopy Offshore Wind project planned for the Humboldt Wind Energy Area.

“Last year we announced that, due to market conditions and increased risk profile, we would delay certain expenditures related to our US offshore wind development projects,” RWE said in a prepared statement. “With the current regulatory and political environment, we have made the decision to reduce the scope of our development activities and the size of our US Offshore team. As RWE, we remain committed with our US business to advancing energy projects that meet rising energy demand, create jobs, and invest in communities.”

It remains unclear how many local employees have been laid off. The Outpost sought additional comment from 10 employees affiliated with the Canopy Offshore Wind project and received four bounce-back emails — including some from people who live here in Humboldt County — each stating that the employee’s “mailbox is no longer active.”

At the end of last month, Vineyard Offshore cut 50 U.S. and European positions, some of which were reassigned to other international projects. Vineyard Offshore spokesperson Kathryn Niforos shared the following statement:

Vineyard Offshore believes that offshore wind is a vital part of the nation’s future energy independence. Our projects will provide over 6 gigawatts of reliable and affordable energy to meet growing energy needs on the east and west coasts, while creating thousands of jobs and fueling economic growth. In an effort to position our projects for sustainable long-term success we have made the difficult decision to reduce our current team size in light of recent market uncertainties. We look forward to continuing to advance these transformative American energy projects in the years ahead.

Reached for additional comment on the recent layoffs, Chris Mikkelsen, executive director of the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District, said he remains “optimistic and focused on delivering a successful project,” referring to the Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal Project slated for the Samoa Peninsula.

“The District remains focused and optimistic about the development of the proposed heavy-lift marine terminal and our ability to provide facilities that support key state and federal government initiatives while maintaining a focus on our local values and people,” Mikkelson said.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Harbor District Announces Massive Offshore Wind Partnership; Project Would Lead to an 86-Acre Redevelopment of Old Pulp Mill Site

- Offshore Wind is Coming to the North Coast. What’s in it For Humboldt?

- ‘Together We Can Shape Offshore Wind for The West Coast’: Local Officials, Huffman and Others Join Harbor District Officials in Celebrating Partnership Agreement With Crowley Wind Services

- Crowley — the Company That Wants to Build a Big Wind Energy Facility on the Peninsula — Will be Opening Offices in Eureka

- Harbor District to Host Public Meeting Kicking Off Environmental Review of Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal Project

- Humboldt Harbor District Officials Talk Port Development As Offshore Wind Efforts Ramp Up

- County of Humboldt, Developers Sign Memorandum of Agreement in a ‘Momentous Step Forward’ for Offshore Wind Development on the North Coast

- Harbor District Responds to Crowley Controversy, Commits to the ‘Highest Ethical Standards’

- LoCO Interview: The Outpost Talks to Crowley Executives About Recent Allegations of Misconduct, Port Development on the Samoa Peninsula and the Company’s Future in Humboldt

- Harbor District Board of Commissioners to Discuss Proposed Offshore Wind Terminal Project, Lease Agreement With Crowley During Tonight’s Meeting

- (UPDATE) Huffman Announces $8.7 Million Federal Grant Toward Offshore Wind Port Development

- Harbor District Commissioners to Discuss Extended Partnership Agreement with Crowley Wind Services During Tonight’s Meeting

- WHOA: Rep. Huffman’s Office Teases $426 Million Federal Grant for Offshore Wind Terminal, to be Announced Tomorrow

- (PHOTOS) The Biggest Federal Grant in Humboldt History? Huffman, Assorted Worthies Gather on Woodley Island to Celebrate $426 Million in Infrastructure Funding for Offshore Wind

- At a Two-Day Conference in Eureka This Week, North Coast Tribes Advocate for ‘Meaningful Engagement’ With Offshore Wind Developers, Federal Regulators

- Crowley Wind Services’s Partner Agreement With the Harbor District Will Expire Without a Lease, Leaving Future Relationship Unclear

- (VIDEO) See What Wind Turbine Assembly Would Look Like on Humboldt Bay, Courtesy of This Presentation From the Harbor District

- Did You See That Big Ship in Humboldt Bay Last Week? That’s the Vessel Mapping the Seabed and Collecting Data for Offshore Wind Development

- INTERVIEW: Harbor District Outlines Next Steps for Offshore Wind Development on the North Coast

- OUTPOST INTERVIEW: Rep. Huffman on Trump’s Offshore Wind Ban