Volunteers from ‘Keep Eureka Beautiful’ Plant Trees Along Fourth and Fifth Streets, After Years-Long Debate Between Caltrans and the City

Stephanie McGeary / Wednesday, June 28, 2023 @ 4:51 p.m. / Community

Trees on Fourth street, between Broadway and Commercial | Photos: Stephanie McGeary

###

In its continued effort to improve Eureka’s streetscapes, local volunteer group Keep Eureka Beautiful is in the process of planting more than 30 trees along Fourth and Fifth Streets, marking the first time the group has been permitted to plant along Highway 101.

Michel McKeegan, a Keep Eureka Beautiful volunteer, told the Outpost that this project has been nine years in the making, and that planting trees along 101 was more complicated than in other areas the group has worked in. The issue was that because the streets are technically a part of the highway, there was a lot of debate about whether Caltrans or the City would be in charge of approving the project. After years of back and forth, Caltrans took over and recently approved the tree planting, McKeegan said.

“I tried to stay up with [the process] and tried to nudge it along,” McKeegan said, when asked why she thought the process was so complicated. “Every once in a while I’d hear ‘We’re almost there.’ Then it would seem like they’d be back at square one.”

In most areas where Keep Eureka Beautiful plants trees (McKeegan said the group has planted around 1,400 trees in the city over the years), the process is pretty straightforward. A resident or business will contact the group to ask for trees to be planted in front of their property. The group’s volunteers then work with the resident or business owner to identify the best spots for the trees, checking to see which locations will not disrupt any underground lines. The volunteers then draft a design plan and submit it to the City for approval. Once the location has been approved, the City takes care of digging up the sidewalk where the trees will be planted, charging $100 per hole. Keep Eureka Beautiful covers half of this cost, as well as provides the trees for free.

For the trees along Fourth and Fifth Streets, Caltrans required that root guards be installed, which McKeegan said also added some time to the process, since the holes had to be dug much larger to add the root barriers. Caltrans also had more specific requirements about what species of trees could be planted. For example, they group was not allowed to plant magnolias – often a popular choice because they are pretty and grow very well here. Caltrans did not want magnolias because the “leaves are too big and don’t disintegrate easily, like other leaves,” McKeegan said.

Keep Eureka Beautiful and the different property owners ended up selecting a mix of Kwanzan Cherry and Yoshino Cherry trees, which have been planted on Fourth Street next to the North Coast Co-op and next to the Best Western Plus Humboldt Bay Inn, and on Fifth Street between L and M Street, in front of several businesses, including Visiting Angels senior care services and the Linden & Company Salon and Spa. On Thursday afternoon the volunteers will also be planting several trees in front of Northcoast Audio on Fifth and C Streets.

McKeegan is excited to finally be able to plant these long-awaited trees, which will help make this well-traveled section of Eureka a little bit more attractive.

“[These are] our two main streets and they represent Eureka to anyone who goes through – visitors and residents alike,” McKeegan said. “It’s really important to make that area as inviting and pleasant as possible.”

Holes dug in front of Northcoast Audio, where more trees will be planted this week

The trees planted on Fifth street, on the other side of Humboldt Bay Inn

Look! More trees! on Fifth Street between L and M

BOOKED

Today: 7 felonies, 15 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Oct. 10

CHP REPORTS

Boyd Rd / Giuntoli Ln (HM office): Trfc Collision-Unkn Inj

Hayfork (RD office): Hit and Run No Injuries

ELSEWHERE

Politico: Johnson says he had ‘thoughtful’ conversation with MTG about bucking Republicans on healthcare

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom signs bill to protect parents’ rights and children

NY Times : How Oakland, Awash in Garbage, Is Trying to Take Out the Trash

Washington Post: China’s demographic crisis means it’s going to run out of workers

Another Day of Cannabis Reform Initiative Panic at the Board of Supes; It’s Now All But Certain That Voters Will Decide on the Controversial Measure on the March 2024 Ballot

Isabella Vanderheiden / Wednesday, June 28, 2023 @ 1:34 p.m. / Cannabis , Local Government

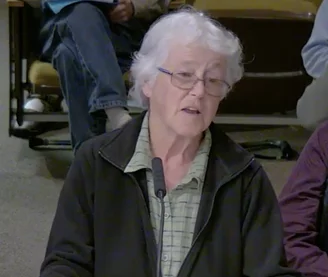

Screenshot of Tuesday’s Humboldt County Board of Supervisors meeting.

###

Dozens of cannabis farmers and allied community members gathered in the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors Chambers on Tuesday morning to speak out against the Humboldt Cannabis Reform Initiative, a controversial ballot measure that would restrict commercial cannabis cultivation across the county.

Proponents of the initiative believe the added restrictions will promote small-scale farming and environmentally responsible cannabis cultivation practices across the county while simultaneously cracking down on water-guzzling mega-grows. However, many local cannabis farmers fear the ballot initiative would decimate their livelihoods and destroy what is left of Humboldt County’s storied cannabis industry.

Members of the board and county staff have met with the organizers of the initiative in recent months to try to find an alternative solution to the ballot measure but the sponsors feel they are “morally obligated” to put the matter before voters.

During Tuesday’s meeting, the board reviewed two separate items relating to the initiative: a report from an ad hoc committee set up to work with the initiative’s sponsors, and an amended analysis of the initiative from staff.

Ad Hoc Committee Report

Earlier this year, the Board of Supervisors agreed to form an ad hoc committee, with Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo and Second District Supervisor Michelle Bushnell as the board appointees, to work with the sponsors of the Humboldt Cannabis Reform Initiative to either modify existing county rules or find an alternative to the ballot measure to address their concerns.

The ad hoc committee met on three occasions and while the meetings were “fruitful,” according to Planning and Building Director John Ford, the initiative’s sponsors ultimately felt the matter should be determined by the electorate.

Arroyo agreed with Ford’s summary, adding that the meetings helped her understand where the proponents of the initiative were coming from, “but it was pretty clear that the proponents of the initiative really wanted to ensure that that this item went to the voters and that an ordinance update would not satisfy their concerns.”

“They wanted something that was really codified in a different way by the voters of the county,” Arroyo continued. “We talked about, you know, the narrow range of options, given that perspective and I think … we’re sort of at a temporary stopping point. Depending on what happens in the future, we may be able to meet again and … have a starting point for a productive conversation.”

The initiative’s sponsors, Elizabeth “Betsy” Watson and Mark Thurmond, largely agreed that the ad hoc committee’s conversations were productive but maintained that county staff and the Board of Supervisors “didn’t really have a good understanding of the initiative,” according to Watson.

“We were not interested in withdrawing the initiative because the purpose and the intention of the initiative are valid,” she continued. “The fact that it cannot be changed – except by vote of the people – is positive because it puts limits on cannabis cultivation that our elected officials are not willing to do. … The initiative prevents a future Board of Supervisors from weakening the essential protections while offering flexibility to support the initiative’s purposes and intent, which is clearly stated.”

Thurmond felt the main objective of the ad hoc committee was to get the initiative’s sponsors to roll over and withdraw the ballot measure in exchange for changes to the Commercial Cannabis Land Use Ordinance, also known as “Ordinance 2.0.”

“[T]he committee acknowledged that any change made to an ordinance today could readily be undone next week or next year depending on the makeup and the mood of the board,” he said. “Thus there’s no guarantee that any agreed-upon language actually would survive more than a year, if that.”

Thurmond emphasized that the main reason the sponsors refused to withdraw the initiative was their “moral obligation” to the “7,000-plus registered voters” who signed the petition to put the measure on the ballot. “They were not told that we might consider brokering a deal or negotiating in some way to not represent the initiative that they signed on,” he said. “We have an obligation to honor the agreement made by those 7,000 citizens.”

Before moving ahead to the public comment portion of the discussion, Fifth District Supervisor and Board Chair Steve Madrone reminded the audience that comments should remain focused on the ad hoc committee’s report rather than the merits of the initiative.

Thomas Mulder, Southern Humboldt cannabis farmer and county planning commissioner, felt as though the ad hoc committee was a “waste of taxpayers’ dollars” and asked the board to refrain from meeting with the initiative’s sponsors in the future. “All these people are trying to do is waste taxpayer dollars,” he said. “Obviously, they don’t want to negotiate. … When this initiative fails, I hope you guys can [sue] them because they’ve wasted so many dollars in this county.”

Natalynne DeLapp, executive director of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance (HCGA), criticized the initiative’s sponsors for failing to do their due diligence and properly inform the public about the potential impacts associated with the initiative. “The [initiative’s] proponents skipped those steps because they were rushing to get enough signatures on the November 2022 ballot.”

“The proponents of the [initiative] never shared the final policy document with the public before it was submitted to the elections office, at which time it could never be changed,” DeLapp said. “When HCGA reviewed the document, we found that 12 of the 13 policies within the document targeted existing small, legal cannabis farmers. … [The document] creates an entirely new section for the county General Plan, one that can only be changed by a future vote of the people.”

Kneeland resident Cheryl Furman, on the other hand, generally spoke in favor of the initiative, noting that she is one of the “7,000-plus people that signed the petition.”

“I believe that this initiative is pretty important … because it would stop cannabis cultivation expansions and it would require wider neighborhood involvement,” she said. “There are many more cars and trucks that are driven by workers and employees at all hours of the night … Meanwhile, these expansions continue to be approved by the planning commission. … This initiative offers much-needed reform for cannabis cultivation in Humboldt County.”

Another speaker, who chose not to identify himself, said he was alarmed by local media coverage of the initiative and decided to read it himself. After doing so, he felt the initiative proposed the appropriate steps to “protect the county’s residents and natural environment from harm caused by large-scale cannabis cultivation.”

First District Supervisor Rex Bohn lamented the fact that the ad hoc committee was not able to resolve the sponsors’ concerns. “I’m sorry, we’re at this point,” he said. “I wish we could have a kumbaya moment. I appreciate the ad hoc that worked on it. A lot of time was spent to get nowhere.”

Bohn added that he would have felt “much more comfortable” with the proposed initiative “if I could get one small cannabis farmer to call me and say, ‘This is going to save me.’”

After a bit of additional discussion from the board, Bushnell made a motion to accept the report and pause the ad hoc committee meetings for the time being.

Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson offered a second to the motion, noting that he voted against Ordinance 2.0 “because it didn’t go far enough from an environmental perspective.” “I believe there is intent around environmental issues that we need to address but I do have concerns about the construct of the initiative process,” he said.

The motion passed in a unanimous 5-0 vote.

Amended Analysis of the Initiative

The board also reviewed – and ultimately approved – an amended analysis of the initiative during Tuesday’s meeting.

The original analysis, presented to the board at its March 7 meeting, identified numerous “unintended consequences” in the initiative. While the initiative is “well intended,” staff’s analysis asserted that the measure, would “have dire consequences to the cannabis industry in Humboldt County.”

Proponents of the initiative disputed the county’s findings and asserted that staff had intentionally mischaracterized the ballot measure with “unfounded assertions and false statements” in an attempt to “influence public opinion on a ballot measure,” potentially violating the Political Reform Act. The sponsors asked the county to “either withdraw the analysis or promptly correct” it.

The staff report notes that the analysis was “not to be used for campaign purposes but [was] written to help the Board of Supervisors and the public, as appropriate, to understand the implications of the [initiative].” Even so, staff agreed to amend the analysis to address some of the concerns outlined in the sponsors’ letter and provide a better understanding of the impacts identified in the initiative.

“The objective is to provide information for the board [and] provide information to the public to increase understanding,” Ford said during Tuesday’s meeting. “One of the concerns expressed in the letter is that the analysis misconstrued the intent of the [initiative]. The analysis is not looking at the intent of [the initiative] but solely what is written, and expresses concerns about how that may be interpreted.”

Michael Colantuono, outside counsel obtained by the County of Humboldt, noted that each member of the Board of Supervisors, as well as the board as an institution, has the First Amendment Right to express their point of view.

“What you cannot do,” he said, “is use public resources to engage in express advocacy. You can’t say ‘vote yes’ and you can’t say ‘vote no,’ but you absolutely can ask your staff to apply their professional expertise to help you and the public you serve to understand what the choice is.”

Speaking during the public comment portion of the discussion, Kevin Bundy, the sponsor’s attorney, urged the board “to keep the county’s role in this neutral and factual” and “not to commit itself to the unfounded interpretations advanced by the initiative’s opponents.”

The vast majority of speakers disagreed and encouraged the board to take a stand. Paul Hagen, a local attorney specializing in environmental law, warned that a neutral stance would “neuter” the board.

“Are the supervisors and individual elected officials willing to take a stance?” Hagen asked. “Your own attorney has said that you can. The [Fair Political Practices Commission] FPPC says that you can. … The idea that you’ve been urged to remain factual is a good idea. The idea that you’ve been urged to remain neutral, neuters you. Why are you elected officials if you have to remain neutral? … I’m not asking you to say one side or the other about your position, I’m just asking you to take a position if you think you should and to speak for your community as elected representatives.”

Hagen added that while the initiative has good intentions, “the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Jackee Riccio, executive director and co-founder of Cannabis for Conservation, similarly criticized the initiative’s “façade as an environmental policy,” arguing that the document “fails to cite relevant peer-reviewed research to support its claims.”

“The lack of consultation or collaboration is blatantly evident to anyone involved in cannabis and environmental research,” Riccio said. “[The initiative] entirely undercuts evidence-supported conservation strategies and the collaborative environmental [efforts] already underway in the county that are far more biologically effective than any practice in this initiative could ever be.”

Laura Lasseter, executive director of the Southern Humboldt Business and Visitors Bureau, spoke to the potential economic impacts associated with the initiative.

“[The initiative] looms as a grave peril to Humboldt’s rural economy, casting a shadow over the potential of cannabis tourism in our region,” she said. “If enacted, this initiative would deliver a devastating blow before our cannabis tourism industry has even had a chance to blossom at all. Humboldt County has long been synonymous with cannabis excellence, attracting visitors from all around the world, the [initiative] jeopardizes this rich heritage by imposing unworkable restrictions on our local cannabis businesses.”

Returning to the matter at hand, Thurmond emphasized that the amended analysis “continued to present false statements and false representations” of the initiative and accused the county of using “a fear-mongering approach” to upset the public.

“I hear the reasons for being upset, and I don’t see those reasons in any of the language in the initiative,” he continued. “I do see it in the language of the analysis [with] false statements about tourism permits and so forth. … That’s an example of how this has just gotten overblown and overwhelmed. And I think the analysis from the county is responsible for most of this problem.”

Another resident, who chose not to identify herself, said she supported the initiative because it “cannot be changed by politicians.” She pointed to Resolution No. 18-43, passed by the Board of Supervisors in May of 2018, which established a cap on the number of permits and acreage for commercial cannabis cultivation. The resolution stipulated that the county must conduct an annual, public review of the permitting and acreage allowances in the county.

“In the past five years, there has been no public hearing and no report detailing the number and status of cannabis cultivation permits,” she said. “The Board of Supervisors agreed to the annual review starting in 2019 and to make the review and cannabis cultivation report public, but this has never happened. We need the Humboldt Cannabis Reform Initiative because it requires environmentally responsible cannabis cultivation, supports watershed health, ensures public involvement and does protect small-scale, environmentally-minded cannabis farmers.”

Following public comment, Bohn asked Ford if he could explain why staff hasn’t followed through with an annual review detailing the status of the county’s commercial cannabis permits.

“At the time that [the] resolution was adopted, there was a thinking that [the] cap would have to be revisited … because there would be pressure for additional permits and additional acreage to be allocated,” Ford explained. “But that could only be done if the regulations that were in effect were successful [in] reducing the amount of surface water that was being used, protecting water quality, that sort of thing. We haven’t been confronted with that, in all honesty, and we have not seen information coming in from the state where the stream gauges have been put in place.”

In an attempt to emphasize the rigorous environmental review process, Bohn asked Ford how many agencies must approve a given permit before it comes back to the county for approval. Ford explained the permit is subject to review by the county Department of Public Works and the Department of Environmental Health, state and federal agencies that own public land, as well as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Regional Water Quality Control Board and, often, area tribes.

Bohn noted that some of the commenters had “made it sound like we’re just throwing these permits out” and wanted to ensure the county is taking the proper steps to mitigate environmental impacts.

“I think we’re being very diligent about looking to make sure that the environment is being protected,” Ford said.

Bushnell asked Ford how the county’s inspection processes have evolved over the years. He explained that the staff had “really stepped into the full inspection process” in the last year.

“We had inspections of 800 sites on the ground,” he said. “We inspected approximately 400 using remote satellite imagery. We’re also in the process of digitizing the permitted cultivation area into the GIS system so that we can look at it immediately and see exactly whether or not there’s been a change based on current imagery. This year we are intending to visit every site in-person [with] boots on the ground inspection of every site.”

Bushnell asked Ford how enforcement would change if the initiative were to pass.

“Well, I think that’s part of the struggle,” Ford responded. “The General Plan doesn’t fit into the existing cannabis ordinance. The General Plan sits separate from that. … I won’t get into specifics but, basically, what we would have to do is modify the ordinance to conform to the general plan. And then, if there are changes that would be needed [to] be inconsistent with the General Plan … that work would have to then be approved by the voters before the ordinance could be amended.”

Wilson noted that, if the initiative were to pass, the county “would be the one on the hook” for any subsequent legal action. “There is no obligation for the proponents to offer any legal resources with relationship to anything after that [election] process,” he said.

After making a few additional comments, Wilson made a motion to accept and file the report with no additional modifications or recommendations. Arroyo offered a second to the action. Before voting, Bushnell stated her opposition to the initiative.

The motion passed in a unanimous 5-0 vote.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- An Initiative to Reshape Humboldt’s Cannabis Industry Qualified for the Ballot, and It Has Growers Worried

- Supes Agree to Put Controversial Weed Initiative on the 2023 Ballot, Though They Hope to Work With Organizers on Alternatives

- Humboldt County Cannabis Farmers Blast ‘Misleading’ Ballot Initiative That Would Impost New Restrictions on Cultivators; Supervisors Form an Ad Hoc Committee to Work on Alternatives

- Proponents of the Humboldt Cannabis Reform Initiative Are Calling Out the Board of Supervisors, County Staff for Allegedly Distorting the Intent of the 2024 Ballot Measure

- Humboldt Supervisors to Revisit Controversial Weed Initiative During This Week’s Regular Meeting

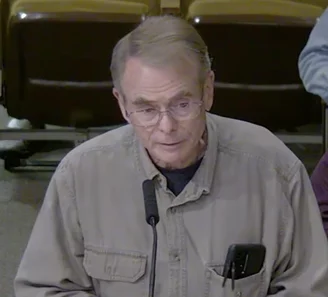

Betty Kwan Chinn Honored by Carnegie Corporation as One of the ‘Great Immigrants’ of 2023

Stephanie McGeary / Wednesday, June 28, 2023 @ 7:30 a.m. / Activism

Images courtesy of the Carnegie Corporation of New York

###

Humboldt’s beloved local philanthropist Betty Kwan Chinn – who has been working to help our homeless population for more than 40 years – has again been recognized for her tireless efforts, being honored as one of the Carnegie Corporation of New York’s ‘Great Immigrants’ of 2023.

Reached by the Outpost, Chinn said that she was completely surprised to receive this honor, which she had actually never even heard of until she was notified that she would be one of this year’s recipients.

“I’m really grateful for this award,” Chinn said in a recent phone interview. “I was totally surprised when they called me. I thought it was a scam and I told my son, and he said, ‘No, it’s a really important organization. Take it!’”

The Carnegie Corporation announces the honorees every year around the Fourth of July, choosing a group of naturalized citizens whose contributions in their fields have enriched society, to recognize the important role of immigrants in our country. Chinn is one of 35 individuals selected this year, including actor Pedro Pascal, Grammy-winning singer/songwriter Alanis Morissette, Elle magazine Editor in Chief Nina Garcia, best-selling author Min Jin Lee, Grammy-winning artist Angélique Kidjo and Academy Award winner Ke Huy Quan.

This is certainly not the first time Chinn has been recognized for her charitable contributions. Last year she received an honorary doctorate from Cal Poly Humboldt, and in 2010 former President Barack Obama selected Chinn as one of 12 recipients of the Presidential Citizens Medal.

Chinn said she does not always have the easiest time receiving acclaim for her work, but she appreciates that the recognition helps inspire others and helps her to raise funds for the Betty Kwan Chinn Day Center and the work that she and her team do.

“I remember when I got the medal from Obama he said, ‘From now on, your name doesn’t belong to you; it belongs to the homeless,’” Chinn said.

You can find more info on this year’s “Great Immigrants” in this press release from the Carnegie Corporation of New York:

Carnegie Corporation of New York today announced its annual list of Great Immigrants, honoring 35 naturalized citizens who have enriched and strengthened our society and our democracy. Each Fourth of July since 2006, the philanthropic foundation has invited Americans to celebrate these exemplary individuals by participating in its online public awareness campaign, Great Immigrants, Great Americans. #GreatImmigrants

The 2023 Class of Great Immigrants is comprised of naturalized citizens from 33 countries and a wide range of backgrounds and fields. For generations, immigrants have come to the United States seeking opportunities for themselves and their families. Among this year’s honorees are individuals who have fostered opportunities for others through their work as educators, mentors, philanthropists, job creators, public servants, storytellers, and advocates.

Additional 2023 honorees are recognized leaders in their fields, including two Nobel laureates, an Olympian, and a member of Congress. Among the honorees are Elle magazine editor in chief and TV personality Nina Garcia, best-selling novelist Min Jin Lee, seven-time Grammy Award winner Alanis Morissette, Hollywood star Pedro Pascal, and Academy Award winner Ke Huy Quan.

“The Great Immigrants initiative is a tribute to the legacy of Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish immigrant who, like these honorees, found success in America, contributed enormously to his adopted country, and inspired others to do the same,” said Dame Louise Richardson, president of Carnegie Corporation of New York, and a naturalized citizen who first came to the United States from Ireland as a graduate student. “The 35 naturalized citizens honored today embody that tradition, reminding us that the contributions of immigrants make our country more vibrant and our democracy more resilient.”

The Great Immigrants initiative is intended to increase public awareness of the economic and societal benefits of immigration. According to the American Immigration Council, a Corporation grantee, immigrants create new businesses at a higher rate than the overall population, with 3.2 million immigrant entrepreneurs generating $88.5 billion in annual income and employing millions of Americans. Immigrants or their children have founded 43.8 percent of Fortune 500 Companies, generating $7 trillion in revenue and employing more than 14.8 million people worldwide. Immigrants also contribute to key workforce needs in America, comprising 15.2 percent of nurses, 25.9 percent of health-care aides, and 23.1 percent of STEM workers.

Additionally, American culture is enriched in diverse ways by the more than 400,000 immigrants who work in creative or artistic occupations.

The Corporation’s Strengthening U.S. Democracy program supports immigrant integration through a portfolio of grantees that focuses on immigration policy reform. Citizenship is the goal of integration, and among the Corporation’s long-term priorities is encouraging eligible immigrants to naturalize. For more than a decade, the Corporation, in collaboration with other philanthropic partners, has supported the New Americans Campaign, which is led by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. To date, the campaign and its national network of nonprofit partners have helped more than 593,000 lawful permanent residents, known as green card holders, apply for citizenship. Services include low-cost application assistance in multiple languages and an online tool that can help with the process. More information is available at www.carnegie.org/citizenship.Since 2006, the Corporation has named more than 700 Great Immigrants, forming one of the largest online databases of its type. The 2023 honorees, the 18th class in the program, will be recognized with a full-page public service announcement in the New York Times on the Fourth of July, as well as through tributes on social media. Please join the celebration by sharing via Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter using the hashtag #GreatImmigrants.

Here is the complete list of the 2023 Class of Great Immigrants:

Wesaam Al-Badry (Iraq) Photographer, Investigative Journalist, and Interdisciplinary Artist

Ana Lucia Araujo (Brazil) Professor of History, Howard University

Kyriacos A. Athanasiou (Cyprus) Professor of Biomedical Engineering, University of California, Irvine

Ajay Banga (India) President, World Bank, and Former CEO, Mastercard

Jean-Claude Brizard (Haiti) President and CEO, Digital Promise

Betty Kwan Chinn (China) Founder, Betty Kwan Chinn Homeless Foundation

Ghida Dagher (Sierra Leone) CEO and President, New American Leaders

Daniel Diermeier (Germany) Chancellor, Vanderbilt University

Miguel “Mike” B. Fernandez (Cuba) Chairman and CEO, MBF Healthcare Partners

Maria Freire (Peru) Global Health Leader and Biophysicist

Nina Garcia (Colombia) Editor in Chief, Elle

Timnit Gebru (Ethiopia) Founder and Executive Director, Distributed AI Research Institute

Karen González (Guatemala) Faith Leader, Writer, Speaker, and Immigrant Advocate

Azira G. Hill (Cuba) Cofounder, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Talent Development Program

Roald Hoffmann (Poland) Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, Cornell University, and Nobel Laureate

Guido Imbens (Netherlands) Professor of Economics, Stanford University, and Nobel Laureate

Angélique Kidjo (Benin) Grammy Award–Winning Singer and UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador

Bernard Lagat (Kenya) Champion Runner and Five-Time Olympian

Min Jin Lee (South Korea) Author and National Book Award Finalist

Ted Lieu (Taiwan) U.S. Congressman, California, District 36

Karen Lozano (Mexico) Professor of Mechanical Engineering, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

Daniel Lubetzky (Mexico) Founder, KIND Snacks and Starts With Us

J. Patrice Marandel (France) Former Chief Curator of European Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Stephen Michael (Guyana) Brigadier General, U.S. Army (ret.), and Senior Executive, UBS

Alanis Morissette (Canada) Grammy Award–Winning Singer-Songwriter, Thought Leader, and Wholeness Advocate

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (Nigeria) Director-General, World Trade Organization

Pedro Pascal (Chile) Actor and Time 100 Honoree

Susan Polgar (Hungary) Chess Grandmaster and Triple-Crown World Champion

Ke Huy Quan (Vietnam) Academy Award–Winning Actor

Helen Quinn (Australia) Professor Emerita of Physics, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University

Julissa Reynoso (Dominican Republic) U.S. Ambassador to Spain and Andorra

Oscar A. Solis (Philippines) 10th Bishop, Diocese of Salt Lake City

Ali Soufan (Lebanon) Chairman and CEO, The Soufan Group, and Former FBI Special Agent

Inge G. Thulin (Sweden) Former Chairman, President, and CEO, 3M Company

Ponsi Trivisvavet (Thailand) CEO and Director, Inari

OBITUARY: Brian Gallagher McCaughey, 1975-2023

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, June 28, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Brian Gallagher McCaughey

December 18, 1975 - June 13, 2023

Brian Gallagher McCaughey beloved son, brother, nephew, cousin, colleague, employee and friend. He passed away June 13, 2023, following a year- long battle with esophageal cancer at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Eureka. He was born December 18, 1975, to Timothy McCaughey and Sarah Ann (Griffin) McCaughey.

He resided with his parents and his younger sister at 63 East Fifteenth Street. He grew up and attended Sunset Elementary School and Sunnybrae Middle School. He attended and graduated from Arcata High School. Following high school, he moved to Lake Tahoe and attended junior college. He returned and attended College of the Redwoods. He graduated from Humboldt State University in 2016.

He was preceded in death by his father, Timothy Hoyt McCaughey; his sister, Katherine Hoyt McCaughey; his maternal grandparents, James and Katherine (Hund) Griffin; his paternal grandparents Hamilton and Roberta Hoyt McCaughey (Reno); his aunt Sally (McCaughey) Jeffers, Reno.

He is survived by his mother, Sarah Ann (Griffin) McCaughey of Arcata; his maternal uncle James Edward Griffin, Jr. and his aunt Annibet (Bauman) Griffin, Glenwood Springs, Colo.; his paternal aunt, Susan (McCaughey) Stone; his cousin Jon Griffin of Glenwood Springs, Colo.; his cousins David Stone, Mark Stone, Penny Stone and Sherri Stone of Reno; Judy Jeffers, Michael Jeffers of Reno; his special friends Amy Davis and her son, Roak, of McKinleyville; special neighbors Mike and Hope Reinman of Arcata; and his colleagues at Hoopa Tribal EPA, Hoopa.

Memories of his intense love for family and friends will be with us always as will his strength and support of others. His love for science and his mastery of scientific data and application thereof will be a reminder of how we must live to protect our water and our air. His love for the ocean, trees and rocks will remind us that this planet is what we must protect.

A celebration of his life will take place Saturday, July 15, at noon, at Redwood Park in Arcata. All are invited to attend.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Brian McCaughey’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Fred Van Vleck, the Sometimes Controversial Superintendent of Eureka City Schools, is Stepping Down After Next Semester

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 27, 2023 @ 5:23 p.m. / Education

ECS Superintendent Fred Van Vleck addresses school board members in closed session following a student walk-out last year. File photo: Andrew Goff.

Press release from Eureka City Schools:

On June 27, 2023, Dr. Van Vleck announced to the Eureka City Schools Board of Education his intent to leave his post as Superintendent in January of 2024.

The Eureka City Schools Board of Education would like to thank Dr. Fred Van Vleck for his 11 years of service (nearly 12 when he departs in January) to the students of Eureka City Schools. Board President Mike Duncan said, “The work Dr. Van Vleck has done in Eureka City Schools will impact our students for generations to come.”

“Dr. Van Vleck is a native of Humboldt County and we are pleased he chose to come home and serve our students,” notes Board Clerk Susan Johnson. “I had the pleasure of serving on the interview panel for Dr. Van Vleck back in 2012. We were looking for a new superintendent who understood our community and was willing to make a long-term commitment to our District. We are proud that when he leaves the District during the next school year, he will be the longest-currently-serving superintendent in Humboldt County. This is a testament to his commitment to the students attending Eureka City Schools.”

While we are disappointed at the news Dr. Van Vleck shared with us on June 27, 2023, we would like to celebrate his many accomplishments as our Superintendent and wish him luck in his future endeavors. We are particularly pleased that he is willing to provide services as the Superintendent in the interim, during our search process. He has committed to work half of the 2023-24 school year to help ensure the transition of the next Superintendent is successful.

During Dr. Van Vleck’s tenure, some of the more notable projects include an over 75 million dollar construction program with projects on every site in the District. He was able to leverage our local dollars and bring in 10’s of millions of dollars from Sacramento. He has been active in the Association of California School Administrators (ACSA), serving as the Regional Vice President and representative to the State Superintendent’s Advisory Council. He has also served on the California School Boards Association Superintendents’ Advisory Council.

As a former Agriculture and Career and Technical Education teacher, Dr. Van Vleck champions programs for students seeking a career in the trades. During his work in Eureka, he was recognized as the California Association FFA Star Administrator for the State of California. Dr. Van Vleck has also been very active in the community, helping to raise millions of dollars for nonprofits, charities, and students with his skill as an auctioneer. He has been an active member of the Eureka Rotary and a member of the Humboldt County Fair Board.

Moving forward, the Board plans to conduct a statewide search for the new Superintendent. The process starts with selecting a firm to work with the community to establish priorities in what qualities and characteristics we are looking for in our next Superintendent. The same firm will then attract and recruit candidates for the Board to interview and select from. The Board is anticipating the new Superintendent to start in January 2024.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Eureka City Schools Settle Lawsuit With ACLU, National Center for Youth Law

- OP-ED: Local Cops Come Out Strong Against Proposition 64, Marijuana Legalization

- Parents Concerned as Eureka City Schools Looks to Restrict Inter-District Transfers

- Cutten School District Will Pay $260,000 for Improperly Enrolling Eureka Kids

- Still Dealing With Declining Enrollment, Eureka City Schools Threatens to Sue Alder Grove Charter School

- As Pressure From Neighbors Mounts, Eureka School Board Poised to Decide What to Do With Abandoned Jacobs Campus

- ‘ERASURE’: A Blistering Report Highlights Disparate Education Outcomes for Native Students, Charts a Course Forward

- After Eureka City Schools Board Votes to End Murals, Community Rallies for BIPOC Student Clubs That Were Planning Murals of Their Own

- With Eureka City Schools Superintendent as Their New Boss, South Bay Union School District Staff Fear a Merger with ECS is on the Horizon

- Eureka City Schools Board Overturns Mural Ban, Making Way for BIPOC Student Art

- As School Districts Pursue Developer Impact Fees, Local Builders Say Added Cost Will Stifle Development

- Hundreds of Eureka High Students Stage Walkout in Support of Beloved Administrator, and They Say His Departure is Part of a Troubling Trend

- Students, Teachers Confront Eureka School Board, Saying Van Vleck’s Bullying Has Sparked Staff Exodus

- ‘Hostile Takeover’: Eureka City Schools Looks to Seize Operation of Academy of the Redwoods, Threatens to Sue Fortuna Union High School District Unless it Complies With That Demand

DRIVE SOBER, DUMMY! CHP Says it Will Implement ‘Maximum Enforcement Period’ To Deter Unsafe and Drunk/Stoned Driving This Fourth of July Weekend

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 27, 2023 @ 1:08 p.m. / Traffic

Don’t be this doofus this holiday weekend. Image by DALL-E, an artificial intelligence

###

As we near the Fourth of July extended weekend, the California Highway Patrol would like to remind you that it will be on the lookout for unsafe drivers. Here is a press release from the CHP:

While the holidays are a time of celebration for the public, they can also be a time of concern for the California Highway Patrol (CHP) and the California Office of Traffic Safety (OTS). The CHP and its public safety partner, the OTS, are working together ahead of Independence Day to address the crisis on California’s roadways by encouraging safe driving behaviors through education and enforcement.

“Reckless driving is a serious concern on California’s roadways, and it is the responsibility of CHP and OTS to help keep the public safe,” said CHP Commissioner Sean Duryee. “Every year, speed is the leading cause of roadway crashes in our state, resulting in thousands of injuries and hundreds of deaths. Slow down and help us make our roads safer for everyone.”To help people arrive safely at their destination, the CHP will implement a statewide Maximum Enforcement Period (MEP) beginning at 6:01 p.m. on Friday, June 30, and continuing through 11:59 p.m. on Tuesday, July 4. Throughout the extended holiday weekend, all available uniformed members of the Department will be on patrol to enhance public safety, deter unsafe driving behavior, and, when necessary, take appropriate enforcement action.

“Maximum enforcement helps save lives and protects everyone on our roads by holding drivers accountable for dangerous, unlawful behaviors like speeding and impaired driving,” said OTS Director Barbara Rooney. “Whether you are traveling near or far, make a plan to go safely before heading to your destination. We want you and your loved ones to enjoy a safe and happy Fourth of July weekend.”Forty-four people were killed in crashes in California during last year’s Independence Day weekend. In addition, CHP made nearly 1,000 arrests for driving under the influence throughout the 78-hour holiday enforcement effort.

Keep yourself and others who are on the road safe by designating a sober driver or using public transit or a ride-share service. If you see or suspect an impaired driver, call 9-1-1 immediately. Be prepared to provide the dispatcher a description of the vehicle, the license plate number, location, and direction of travel. Your phone call may save someone’s life.

“We encourage you to safely enjoy your holiday weekend,” added Commissioner Duryee. “Travel at a safe speed, avoid distraction behind the wheel, buckle up, and drive sober. Rest assured, CHP officers will be working diligently to protect those who are traveling on California’s roadways.”

The mission of the CHP is to provide the highest level of Safety, Service, and Security.

NEED FRUIT AND VEGGIES? Food for People Handing Out Fresh Produce Throughout the Summer, Starting At the Bayshore Mall This Week

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, June 27, 2023 @ 11:08 a.m. / Community , Food

File photo: Food for People

###

Food for People press release:

Food for People will once again host seasonal Free Produce Markets this summer in Eureka and Garberville. The Free Produce Market distributions will run June-September to ensure that everyone can have access to nutritious, seasonal produce, and some pantry staples needed for good health.

The first drive-thru Bayshore Mall distribution will take place on June 29 from 11 am - 1 pm at the North Parking Lot. The Bayshore Mall distribution is a drive-thru distribution while Garberville will be walk-up only.

Upcoming Free Produce Market Distributions:

Eureka Bayshore Mall - 11 am - 1 pm

June 29, July 27, August 24, September 28 (Drive-Thru)Garberville Presbyterian Church – 10:30 am - 12 pm

July 11, August 8, September 12 (walk up only)Food for People, the Food Bank for Humboldt County, provides vital food resources for the community through hard times- from economic downturns to wildfires, and so many of life’s challenges. As pandemic assistance programs come to an end and food costs are on the rise many people are having a tough time putting food on the table.

Food for People works to alleviate local hunger and improve the health of the community through its 18 programs and strong community partnerships. These programs include a countywide network of emergency food pantries; mobile produce distribution to rural areas of the county; food assistance for children, seniors, and homebound individuals; nutrition education; and local food recovery and gleaning efforts. Food for People distributes nearly 2 million pounds of food annually to the county’s most vulnerable members. For more information, go to www.foodforpeople.org or call (707) 445-3166.