Conceptual drawing of the Creamery Row Townhomes affordable housing project in Arcata.

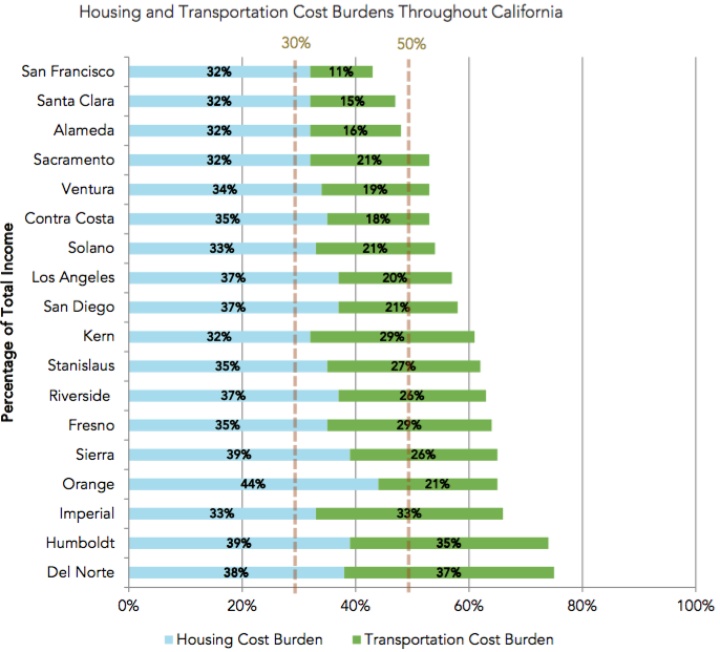

If someone told you that it’s more expensive to live in Humboldt County than in San Francisco, you’d probably be skeptical — and rightly so: San Francisco has the highest rents in the state by a pretty wide margin. But if you add in the cost of transportation and then measure costs as a percentage of total income, things start to look a lot different.

In fact, Humboldt County residents spend a higher percentage of their income on housing and transportation than almost anyone else in the state, according to a recent report from the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD).

See the graph below:

Source: Center for Neighborhood Technology, Housing and Transportation Index.

Housing is considered “affordable” if it takes up no more than 30 percent of your income, including utilities. That’s the benchmark set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This HCD report expands the picture a bit by looking at both housing and transportation costs and using a combined affordability threshold of 50 percent of income.

As the graph shows, most counties in the state exceed that mark, but Humboldt is among the worst. Living here it takes roughly 75 percent of our income, on average, to cover housing and transportation costs. (The graph, as you may have noticed, shows just a sampling of California’s 58 counties; Humboldt actually has the fourth-highest cost burden in the state, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Housing and Community Development.)

Transportation costs are naturally higher in rural counties like ours. The HCD report, and this post, focus instead on the challenge of providing affordable housing. Humboldt County, like many other counties throughout the state, isn’t providing enough housing to meet our needs. In fact, according to the HCD, Humboldt County didn’t build even half as many homes as we should have based on our Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) between January of 2007 and June of 2014 (the period examined in the report).

The limited supply drives up demand, inflating housing costs beyond the reach of the poorest residents.

“Working full-time at a minimum wage of $10 an hour, a renter or homeowner can afford $520 per month in housing costs,” the HCD reports. The average monthly rent on two-, three- and four-bedroom houses in Humboldt County is $1,760, according to the latest Humboldt Economic Index, a report produced by Humboldt State University’s Economics Department. In order for that to be considered “affordable” by the HUD standard you’d need a household income of $70,400 a year. That’s more than 23 percent higher than Humboldt County’s average household income of $57,163.

Of course, there’s always an asterisk when discussing income in Humboldt County — an asterisk shaped like a pot leaf. Much of the revenue generated by the county’s largest cash crop remains off the books, though the industry is also fueling a land rush, driving property values higher. Topics for another day.

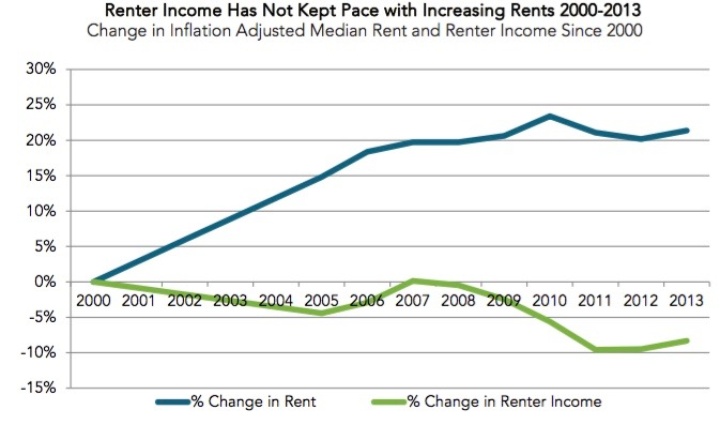

Across the state, renters’ incomes actually declined between 2000 and 2013 while rents climbed by more than 20 percent:

Graph courtesy the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

Why does all this matter? The HCD notes that the lack of adequate and affordable housing has “far-reaching policy impacts on the quality of life in California, including health, transportation, education, the environment, and the economy.” It especially hurts vulnerable populations such as seniors, tribes, people with disabilities and, obviously, the homeless.

The Outpost spoke with officials from the county and several local cities to find out how they’re dealing with the challenge of providing housing. While a big part of the equation lies beyond their control (government doesn’t actually build new housing on its own, after all), these local officials are bringing a number of resources to bear as they try to stimulate the local housing industry.

Rio Dell

“Cities aren’t always in control of developers’ interest in the town,” said Rio Dell City Manager Kyle Knopp. Development is primarily market-driven, and no place in Humboldt has likely had a tougher go in recent years than Rio Dell. This was a lumber town, home to employees of the Pacific Lumber Company and Eel River Sawmills, both long gone.

“With the demise of that industry combined with the recession, Rio Dell is probably the epicenter or ground zero for a lot of the economic occurrences of the past 15 to 20 years,” Knopp said.

For roughly 40 years developers have been eyeing the Dinsmore Plateau for a subdivision project, but Knopp said it would require a huge investment in infrastructure, including tens of millions of dollars to build new roads.

The city has already faced infrastructure hurdles, like when the Regional Water Quality Control Board issued a cease-and-desist order for Rio Dell’s wastewater treatment plant, forcing the city to build a new, state-of-the-art facility, which came online in 2014.

But large housing projects have failed to materialize. Danco planned to build a 30-unit senior housing project in Rio Dell, but the project didn’t materialize because Danco was unable to leverage state and federal financing, Knopp said.

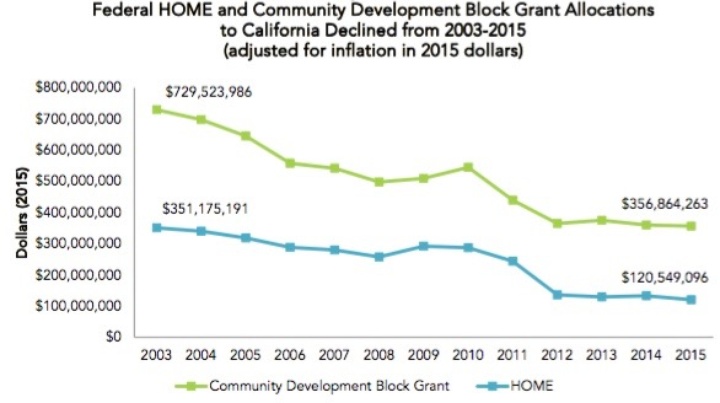

This is one of the main challenges to building new housing: the increased scarcity of government subsidies. Federal grant money has steadily declined in recent years (see graph below), and state funding has become more competitive since the legislature dissolved redevelopment agencies in 2012.

Graph courtesy the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

“That leaves it kind of up to local governments to subsidize [projects] and move them forward,” Knopp said. “It becomes next to impossible for us to dedicate local funds to meet what is really a statewide objective.”

But the city has taken measures to improve the situation. Rio Dell recently lowered its minimum lot size for developable properties, which has led to some new housing units being built. The city has also updated its zoning and is currently updating the housing element of its general plan.

”The good news: There is definitely an uptick of interest in investing in the town,” Knopp said.

Arcata

If Rio Dell has had the toughest go among local cities in recent years, Arcata may be doing the best. Since the beginning of 2014 Arcata has seen 118 new housing units built, including 49 units of low- or very low-income housing. And the city has hundreds more units in the pipeline.

“We have a robust affordable housing program in Arcata,” said David Loya, the city’s director of community development. That has long been the case, but the city has changed strategies in recent years. In the absence of redevelopment money Arcata now relies more heavily on community development block grants, with extra help in the form of tax credits and, when possible, federal HOME grants.

Loya said the city tries to be developer-friendly, too.

“We generally work to support our housing partners [and the] developer community,” he said. “We help make loans, make land available and make sure the permitting goes through.”

Some of the recent projects in Arcata include a series of low-income townhouses in the Creamery District, three low-income units on O Street in the Arcata Bottoms and Arcata Bay Crossing, the 31-unit apartment complex serving the homeless, very low-income and mentally ill.

The Unincorporated Areas

For many years the development community griped about Humboldt County’s Planning and Building Department, saying it had an anti-development bias and hindered projects with red tape.

The HCD report agrees that bureaucratic barriers and constraints such as lengthy review processes and political opposition can delay or prevent housing projects. But Humboldt County’s new planning and building director, John H. Ford, says the county is more than willing to facilitate new growth.

“I would also say that in the environment I believe we’re in there is desire to see appropriate housing built,” Ford said. “I think we have that direction and support from the supervisors to planning commission.”

Housing construction tends to happen in boom-and-bust cycles, Ford said, and many different factors have to come together to create a boom, including financing and the developers’ perceived return on investment.

Paula Mushrush, the county’s housing and grants coordinator, said the county faces a couple of extra challenges in outside pursuing funding. “Our poverty rate went down substantially in the 2010 census,” Mushrush said. That makes it harder to compete against cities like Arcata, which has a lower-income population and thus qualifies for more grants.

Plus, many of the available grants are going to support “smart growth” development, financing projects that are close to utilities and public transit.

”Today’s marketplace is highly directed toward walkable communities, more of an urbanized setting,” Ford said.

Since the county government excludes incorporated cities it has fewer areas that meet those parameters. (McKinleyville and the Cutten and Myrtletown neighborhoods of Eureka are the primary exceptions.)

Another factor: “We don’t have a lot of big investors,” Mushrush said. In more urban areas like Santa Rosa, big corporate partnerships and LLCs will finance projects of 120 units at a time. That wouldn’t necessarily work well here.

“It’s not like our growth rate is significant,” Ford pointed out. Humboldt County’s population is projected to grow by less than 9,000 from its 2010 mark (131,600) to 2020.

“What Arcata’s building right now is going to flood the market for a few years,” Mushrush said.

But Humboldt County still has unmet housing needs — particularly for seniors and the homeless.

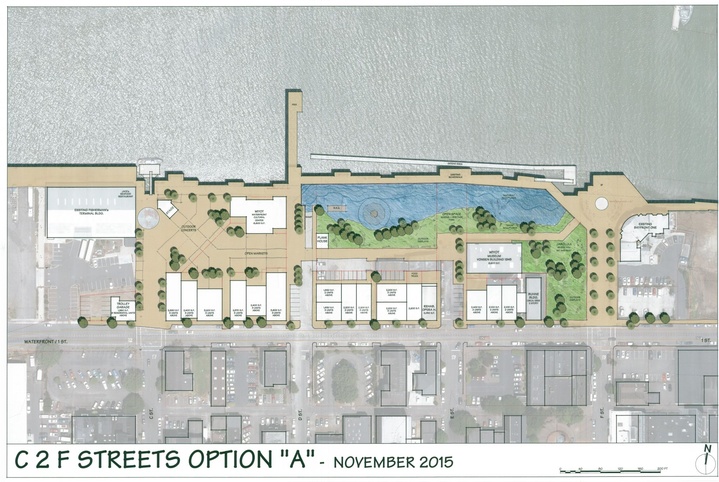

A conceptual design for a mixed-use development along Eureka’s waterfront. | Image courtesy City of Eureka.

Eureka

Eureka Community Development Director Rob Holmlund said that building new low-income housing isn’t the only way to solve that problem.

“We need to create market-rate housing as much as we need affordable housing,” he said. The American dream is to buy a starter home and then eventually, as your career advances, move up to something larger. This keeps the inventory of cheaper homes available. But when there’s a limited supply of market-rate homes it becomes harder for people to move up that chain, Holmlund said.

But with Eureka more or less “built out,” meaning most of the city’s available residential-zoned land is already developed, how can it meet the housing demand?

“Eureka is working toward creating more urban housing,” Holmlund said. “It’s one thing we can do that no one else [in Humboldt] can — create upper-floor housing in taller buildings in downtown Eureka and Old Town.”

This style of development was incorporated into the conceptual designs for the waterfront development project between the C and F street plazas, with retail businesses on the ground floor and apartments above. Holmlund is excited by the idea, saying there will be demand for “really killer studio apartments and condos that are hip.” The city is looking to do this kind of development anywhere north of Sixth Street, from Broadway to Myrtle Avenue.

The city has a strong historical precedent for this type of development.

“It’s like what was build from the 1870s to 1940s,” Holmlund said, “build big buildings we can all be proud of and htve housing on the upper floors.”

To allow such projects, the city’s zoning code will have to be changed, but Holmlund said the City Council is supportive of that concept.

Meanwhile, the city has officially adopted a “housing first” strategy to addressing homelessness. Rather than making people qualify for housing by participating in readiness programs and proving they’re sober, the housing first model aims to get people into permanent housing as a first step before following up with services.

The county has been working the City of Eureka and local landlords to try to meet that housing need. Eureka’s housing stock is quite old. Only about three percent of the city’s houses were built after 2000. Holmlund believes the upper-story developments could result in hundreds of new units downtown. And even if they aren’t specifically designed for low-income renters the increased housing stock should relieve pressure on the market and help lower rents.

CLICK TO MANAGE