Shelter Cove | Copyright (C) 2002-2015 Kenneth & Gabrielle Adelman, California Coastal Records Project, www.Californiacoastline.org.

On a steep coastal property in Shelter Cove lies a trail that descends several hundred feet from a tall bluff to the black sand beach below. The top of the bluff, which is accessible by car, offers a panoramic view of the majestic Lost Coast. From there the trail switchbacks down the bluff face and narrows to a gravel footpath, which runs through thick chaparral before arriving at a clearing that sits on a shelf overlooking the beach. A large rock fire circle has been built at the edge of this little plateau, and longtime local surfer Steve Mitchell sits on the edge of the circle eating a sandwich, sipping a beer and gazing at the breakers rolling in.

The switchbacks at the top of the trail are relatively new, providing a wider and steeper route than the previous footpath. Mitchell first noticed the new way down early this year. He’d come for the first good south swell of the new year, and while floating with his board he glanced back at the bluff and noticed something different.

“I paddle out, turn around and look up, and there’s this big cut going down the hillside,” he said. Brush had been cleared and earth had been moved, leaving swaths of exposed soil. Mitchell didn’t think much more about it that winter day, but others had noticed the trail work, too, and somebody (it’s unclear exactly who) complained to the county.

Turned out the work had been done without a permit, and that was a problem. After an inspection county workers found that the grading and brush clearing had potentially destabilized the hillside, and officials suspected that Roundup herbicide had been used to kill off some of the vegetation. This despite the proximity of Dead Man’s Creek, a picturesque little waterway that rolls down the bluff and empties into one of Humboldt County’s premier surfing locations.

The property is owned by a wealthy Florida man named Ben Yomtob, who says he was unaware that he needed a permit for the trail work. He’s now working with local and state officials to address the problems created by this unsanctioned development, but he says the real threat to the environment here lies at the other end of his private trail, on the little plateau with the fire circle.

Local surfers, including Mitchell, built the pit 15 years ago in memory of a friend, unaware that they were building on private property. And in the years since, the spot has become a magnet for locals and visitors alike. The owner looks down from the top of the bluff — where he hopes someday to build a home — and sees people building huge, dangerous bonfires. Illegal campers urinate and defecate into the creek. And visitors toss garbage into this sensitive habitat.

Yomtob blames surfers — or at least he did initially. The local surf community says the blame lies with out-of-towners, including some surfers but also the so-called trimmigrants: people drawn to this remote corner of Humboldt County in hopes of finding work trimming marijuana buds.

Now, although Yomtob and surfers seem to have reached a temporary truce, locals and regulators alike are watching to see if it holds.

All together, the trail connects not just a bluff and the beach but also some of the cultural forces that have shaped Shelter Cove, California’s most remote coastal community, including surfers and real estate investors, outlaws and government regulators. And while those cultures have historically clashed, county government officials are working to unite Yomtob with the local surf community behind a shared ideal: Protecting this stunning coastline.

A surfer walks past the mouth of Dead Man’s Creek | Ryan Burns

Local lore has it that the first surfing ever done in Humboldt County was done in the frigid waters of Shelter Cove. Back in 1952, a surfing dentist named John H. Ball moved with his family from Southern California to Garberville, where he set up a dental practice. Better known by the nickname “Doc,” Ball was a charter member of the Palos Verdes Surf Club, California’s first such club, and though he died in 2001 at age 94 he’s still renowned as “the original surf photographer.”

Ball hadn’t been in town long before he drove 24 winding miles west to the coastline, put his board in the frothy waters of the Cove and began riding the waves. By the mid-’60s a Shelter Cove surf scene had developed, complete with a pair of ragtag surfing contests in 1964 and ‘65.

To this day, the Cove remains remains arguably the most cherished spot among local wave-riders, particularly the steep break in the bay’s rocky, southern crescent, near the mouth of Dead Man’s Creek. The spot, which is particularly good during a south swell, is known simply as Deadman’s.

From the narrow, black sand beach — or, even better, from out on the water — you get a great view of the rugged shoreline, where tectonic uplift and the pounding tides have carved the western edge of the King Range mountains. Slopes covered in redwoods and fir end abruptly with a jagged rock wall that stretches from the Eel River delta to Rockport Bay in Mendocino County.

Shelter Cove | Ryan Burns

This is the Lost Coast, so named because its imposing terrain has made it nearly impervious to development. The exception is the remote and delightfully odd little town of Shelter Cove (pop. 693), a fishing village partially transformed into a fly-in vacation destination through a rash of late-‘60s development so haphazard, so poorly conceived and executed that it would later be recognized as a debacle and a con job.

In 1966 developers embarked on an ambitious subdivision, hoping to build more than 4,000 homes across 2,500 rugged acres. Forty miles of asphalt were laid like ribbon along the steep hills of Shelter Cove. But many of the resulting lots were on ground so steep and unstable that they simply weren’t buildable. Over the years, many out-of-towners have purchased these lots sight unseen, often with hopes of retiring on this beautiful coastline, only to find out later that their property could never accommodate a house.

The houses that are here — along with a couple stores, restaurants and cliffside motels — are scattered around an airstrip on a plateau that juts into the Pacific. There’s a bleak romance to this town, where buildings cling like barnacles to the crumbling edge of America. The region has inspired surfers, travelers and writers.

Facebook profile picture of Ben Yomtob

Facebook profile picture of Ben Yomtob

It also inspires Ben Yomtob, a commercial real estate investor from Boca Raton, Fla. In 2004 Yomtob purchased the 65-acre oceanfront parcel that runs along the majority of the bay at the south end of town. Known as Seaside Ranch, it’s the largest private landownership in Shelter Cove.

Yomtob hired a trail crew in the summer and fall of 2014 to cut the switchbacks with hand tools and attack vegetation with herbicide to clear a path he hopes to use as a private trail. According to Humboldt County Senior Planner Steve Lazar, this pathway wasn’t new.

“It looks like it was a road at some point in ’60s, but it fell into disuse,” Lazar said. Like other projects of the era, the road was built without the rigorous government oversight required today. In fact, the reckless development of places like Shelter Cove sparked political blowback that led to the 1972 Coastal Initiative, which established the California Coastal Commission, and the 1976 Coastal Act, which extended the new agency’s authority indefinitely.

Lazar said the narrow road may have been covered by a landslide at some point. Regardless, any clearance or property reclamation in the state’s Coastal Zone nowadays is considered development. And since Humboldt County has a certified local coastal plan, the county has exclusive authority for coastal permitting.

“He claims he had no idea the work he was doing needed a permit,” Lazar said. “He’s learning the hard way.”

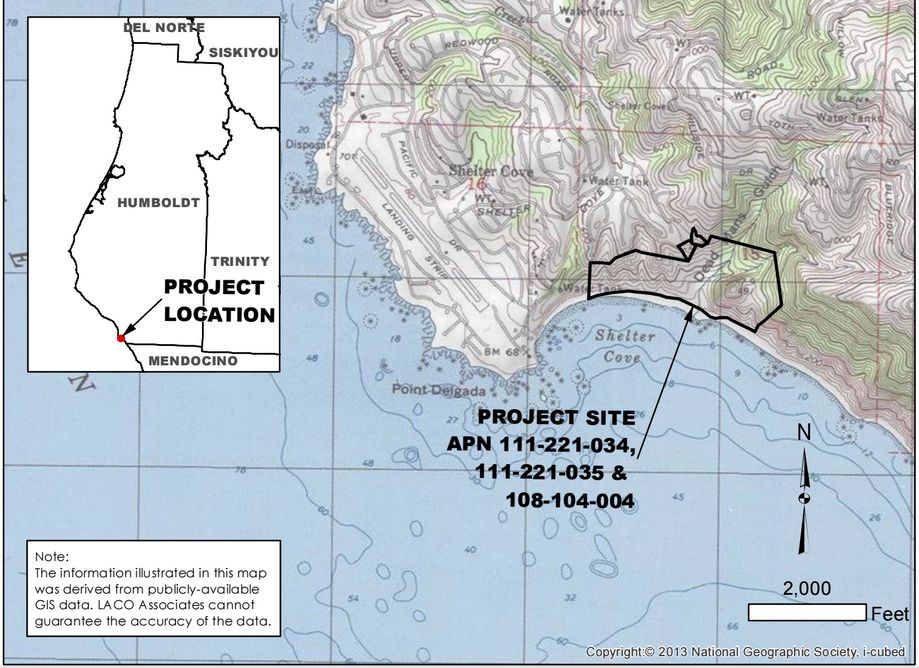

Map of Yomtob property created by LACO Associates | Courtesy Humboldt County

Map of Yomtob property created by LACO Associates | Courtesy Humboldt County

The county didn’t find out about the trail work until February of this year, and when it did officials ordered a geologic and engineering evaluation. Given the season’s usual threat of rain (though not so much this year, as it turned out), officials felt immediate action was necessary to prevent erosion and protect the sensitive resources in the gulch below. They were worried that the newly exposed soil could succumb to slope failure, causing dirt runoff into Dead Man’s Creek.

“The principle concern we had was to get some measures in place to stabilize what had been done and prevent worsening of the disturbance,” Lazar said.

Yomtob — much to his credit, Lazar said — responded quickly. He flew out from Florida to meet with the Planning Department, and after learning about the rules and regulations he hired local geological engineering firm LACO Associates to do emergency stabilization measures. By all accounts that work has been thorough and successful. LACO installed biodegradable jute netting and fiber rolls on the exposed soil slopes and constructed “rock armoring” at the outlet of a recently installed culvert. For the time being, the hillside appears stable.

“That [work] was approved under an emergency coastal development permit,” Lazar explained. Which doesn’t mean that the trail itself has been approved. Yomtob is working with LACO on a background investigation on the property, hoping to get an after-the-fact permit application. But Lazar said it’s not an open-and-shut matter.

“This is an unusual piece of private real estate,” he said. “We don’t see a lot of projects like this.” With the exception of the very top of the parcel, which is zoned single-family residential, Yomtob’s property is zoned Natural Resources. Such land is primarily intended for fish and wildlife habitat management, coastal access facilities and resource-related recreation. A trail would seem to fit those latter two uses, but since this is a private trail, Lazar said, “we’re kind of treading new ground.”

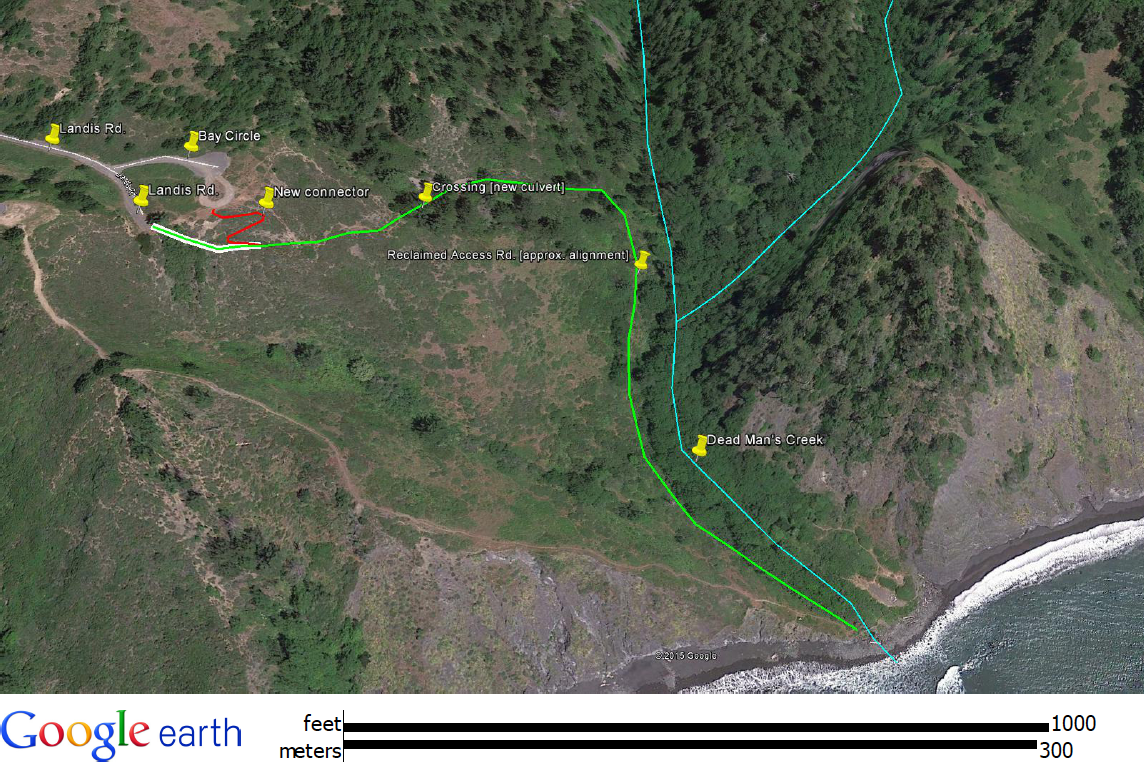

In this image created by the Humboldt County Planning & Building Department, the crooked red line in the upper left shows the path cleared by Yomtob. The green line represents the historic access road at the site, and the forked blue line follows Dead Man’s Creek. (Click to enlarge.)

In this image created by the Humboldt County Planning & Building Department, the crooked red line in the upper left shows the path cleared by Yomtob. The green line represents the historic access road at the site, and the forked blue line follows Dead Man’s Creek. (Click to enlarge.)

In pursuing both the emergency permit and coastal development permit, Yomtob has had to coordinate with the agencies he was supposed to contact in the first place, including the Coastal Commission, the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, which will be consulted regarding any unearthed artifacts from the native Sinkyone people, who were once the only inhabitants of Shelter Cove.

“LACO is in the process of drafting a larger plan that will be presented to the county and also the Coastal Commission,” since both agencies have jurisdiction, Lazar said. The permit process will require an evaluation of alternatives, including full restoration of the site to its pre-development condition.

This is how the trail looked earlier this year before LACO Associates performed stabilization work.

This is how the trail looked earlier this year before LACO Associates performed stabilization work.

The Outpost tried to arrange an interview with Yomtob, leaving several messages on his work and cell phones and sending emails. He eventually responded via email, saying that due to a series of events in his personal life, including a looming surgery, he would be unable to comment for more than a month. Instead he directed us to correspondence he’s had with the local surfing community, including Humboldt Surfrider, the local chapter of the nonprofit Surfrider Foundation.

Lazar had reached out to the surfing community for help in addressing Yomtob’s concerns about fire, garbage and abuse at the other end of the trail. Lazar contacted veteran local surfers Steve Mitchell and Bill Hoopes as well as Humboldt Surfrider Chair Jennifer Savage and put them in touch with Yomtob. Yomtob told them in an email that the situation is dire.

“The land is at risk,” he wrote. “There are raging fires emanating from the campground/surfer staging area. Also there is use by some that is causing disturbances and leaving wakes of residue. As I see the disturbances that are left behind when visitors come and go and the raging fires that are happening in and outside of the fire ring, it makes me CRINGE.”

Yomtob has reached out to various agencies in recent years, looking for help managing the lower regions of his property. According to correspondence with the the county he has contacted the Shelter Cove Resort Improvement District; the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District; and the federal Bureau of Land Management.

“It is my understanding that no agency ever expressed significant interest,” Lazar said.

The slope has now been reinforced with biodegradable jute netting and fiber rolls | Courtesy Humboldt County

The slope has now been reinforced with biodegradable jute netting and fiber rolls | Courtesy Humboldt County

Yomtob says the liability concerns are one reason why he cleared the trail. In his email to the surfers he said the trail could function as a firebreak while also providing access to firefighters and paramedics should someone get injured below.

A member of the Shelter Cove Volunteer Fire Department told the Outpost that while they weren’t contacted ahead of time, the trail could help them reach people when the tide is too high to access the beach by vehicles. The department even conducted a fire drill onsite recently.

Yomtob admits to having personal reasons for the trail, as well. While exploring the property in 2007, he explained in his email to surfers, he was bitten by a tick and infected by Lyme disease. He has also contracted poison oak and torn his meniscus, leading to arthritis, he wrote. The trail seemed a logical solution.

Now that he’s working with the appropriate agencies to address the top of the trail, Yomtob implored the surfers to help control the abuses at the other end.

“I am unable to control what is happening on my property in this highly sensitive area,” he wrote. “From my observations over the last 11 years, 90% of the property users are surfers. … I ask you to please consider jumping on board with this worthy cause that lands so close to home for you. I’m not asking for much and the impacting benefits could be enormous.”

Surfer Steve Mitchell enjoys a sandwich at the fire pit he and some friends built as a memorial for their deceased friend, Carlos Mier. “We didn’t realize we were putting it on private property or we never would have done it,” Mitchell said. | Ryan Burns

Surfer Steve Mitchell enjoys a sandwich at the fire pit he and some friends built as a memorial for their deceased friend, Carlos Mier. “We didn’t realize we were putting it on private property or we never would have done it,” Mitchell said. | Ryan Burns

Steve Mitchell and Bill Hoopes grew up surfing at Deadman’s, and they describe it in reverent tones.

“Deadman’s is pretty much a diamond in the rough,” Mitchell said in a recent phone interview. “You got the redwoods, the fir forest, big mountains that come right out into the ocean.” He remembers standing on the coastline with a young guy from Kauai, which has a pretty stellar surf scene of its own. “This kid was looking up and down the coast. His head was on a swivel, and he kept saying, ‘Big country,’” Mitchell recalled with a chuckle.

Hoopes, who started surfing the Cove in 1964 or ‘65, said, “The Cove is special because it’s a great place to learn.” From town there’s a ramp down to a boat launch where a jetty (made from boulders taken from Dead Man’s gulch) serves as a wavebreak for smooth entry. This jetty is called “the rock.”

“Most of us guys learned to surf there,” Hoopes said. The Cove has three distinct breaks, he explained: the rock, first reef and second reef, aka Deadman’s. “We just kind of gravitated towards Deadman’s eventually because the waves are bigger, and we discovered you could go both ways, right or left.”

Surfers prepare to paddle out at Deadman’s | Ryan Burns

Surfers prepare to paddle out at Deadman’s | Ryan Burns

While Hoopes and Mitchell were concerned about Yomtob’s trail work, they agree that people are abusing this land, and something needs to be done.

“This is a magical spot, man,” Hoopes said. “It’s a great wave. And what someone does to that watershed is affecting all of us — the fish, abalone, everything. It’s just awful.”

“He’s concerned about fire,” Mitchell said of Yomtob. “I am too. That’s a big concern.” People don’t confine their fires to the pit, instead lighting blazes further up the gulch among the foliage and dumping their garbage without a second thought.

But it’s not locals, Mitchell insisted. “Local surfers have been good stewards of this property,” he said. “Local surfers don’t camp there; we live here.”

Hoopes said the beach has gotten exponentially busier since he was young, largely because of road improvements. The road from Garberville used to wash out fairly regularly. But people keep moving into Shelter Cove and setting up “full-time lives” there, Hoopes said.

“And face it,” he added, “more people, more garbage. That’s the way it is anywhere in the world.”

The marijuana industry in Southern Humboldt has exacerbated the problem. “There’s a bunch of young-ass wannabe gangsters out there,” Mitchell said, referring to newcomers hoping to make their fortunes growing weed. They don’t care about the environment, Mitchell said, and that attitude extends to the hired help.

A dog waits patiently while its owner rides the waves | Ryan Burns

A dog waits patiently while its owner rides the waves | Ryan Burns

Last summer Mitchell encountered a group of “trimmigrants” who’d come to Humboldt from France and Belgium. He saw them urinate and defecate into Dead Man’s Creek and leave garbage everywhere. “I asked, ‘Is this how you live in France?’ They didn’t think they were doing anything wrong. I guess they thought there was trash service.”

Since there isn’t, Mitchell and a few of his friends decided to clean up the trash themselves. Last summer they gathered two full loads of trash in the back of his Toyota Tundra. “That’s a lot,” Mitchell said. “We’ve found medical waste, just white trash nasty-ass bullshit.”

Surfers like Mitchell and Hoopes often rinse off their wetsuits in a pool at the bottom of Dead Man’s Creek, but Mitchell said he won’t get in that water anymore. It recently smelled like chicken manure, he said.

Yomtob is right to be concerned about these problems, Hoopes said. “The guy has his rights,” he said. “People are literally trespassing on his land. That’s a fact. He owns it. He’s got his rights. We have to recognize that and work together.”

Kicking people off his land entirely might be impossible. According to state law, once the general public has an established history of coastal access somewhere, including trails, beaches and bluff tops, those areas are generally granted a permanent public easement.

Some local surfers were concerned that Yomtob might contest those rights, but in his email he insisted that’s not the case.

“There is no threat of access down my beach for the surfers,” he wrote. “In fact, I am going to climb the tallest mountain and let all surfers know that as the owner of the beach that accesses Dead Man’s surf break and the voice of this beach: WE WELCOME YOU!”

But with that access comes some shared responsibility, Yomtob suggested.

While local surfers aren’t the problem, Mitchell said, “Surfers as a group … are the least conscientious of anyone who comes to our area. Not all of ‘em, but some just don’t seem to care.” He called these out-of-towners “aggro surf nazis” and described some of their crimes. One crew made lean-tos using plastic tarps at Big Flat, another beloved surf spot, and then left them to decompose. The blue plastic broke down in the sun and got scattered all over the beach. Local surfers try to police such activity, but it’s an uphill battle.

“We’ve already been policing [Yomtob’s] property as good stewards of land,” Mitchell said. “We’ve already taken on that responsibility, and we’re trying to get people to be more respectful.”

What he’d like, though, is permission from Yomtob to act as official spokespeople and run people off his property when necessary. It’s unclear what Yomtob thinks of this, but the issue is likely to come up as the cooperative efforts continue.

Looking down at the coastline from the improved trail | Courtesy Humboldt County

Looking down at the coastline from the improved trail | Courtesy Humboldt County

Hoopes took it a step further, saying some restrictions should be placed on the bluff. “I think, honestly, people ought not to camp there,” he said, adding, “You can quote me. There are no bathrooms there. Unless people are going to haul out their waste, we have a problem.”

In some ways, Mitchell and Hoopes don’t have a whole lot in common with Yomtob. They grew up in this small and wild community, and they’ve been surfing the break at Deadman’s for decades. They can reminisce about the town before it was transformed by greedy developers, before surfers from across the country and beyond started making the trek to Deadman’s, and before the county’s underground marijuana industry became the violent, unruly beast it sometimes is today.

Yomtob’s perspective is different. He first visited this place with his family in the 1970s and then left. He has returned many times as a visitor, as a potential investor and finally as a property owner. But he makes his living on a coast that’s as far away from Shelter Cove as you can get in the United States, both geographically and culturally.

And yet all three men used the same terms when describing the place — “sacred” and “special.”

While Yomtob tries to straighten out the permitting for the work at the top of the bluff, he hopes to strengthen the connection with local surfers down below. In an email to them earlier this year he observed, “The many surfers and other visitors that I have spoken to consider this spot spiritual and sacred and I do as well.”

CLICK TO MANAGE