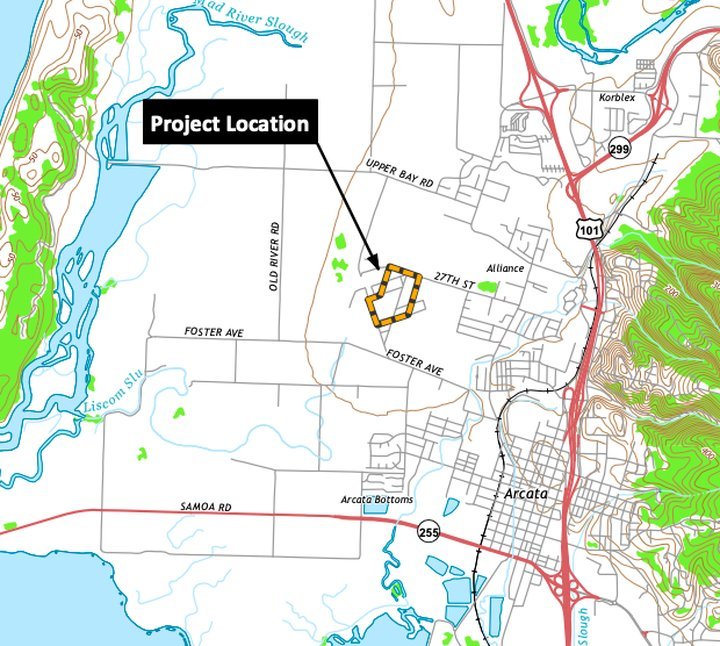

Map showing the site of Sun Valley Group’s planned cannabis farm in the Arcata Bottoms. | Image via County of Humboldt

###

We offered a cursory recap of yesterday’s meeting in the post linked above, but let’s take a closer look at the details of the 5.7-acre cannabis cultivation project that the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors approved on Tuesday — and also at the circuitous and sometimes confused decision-making process that got them there.

At the outset, Planning and Building Director John Ford reminded the board where they’d left off back on June 22 — namely, asking staff to investigate the effectiveness of the patented odor-control technology proposed for use in Arcata Land Co.’s weed farm. The smell of growing cannabis has been one of the major concerns among neighbors of the property, which is owned by the Sun Valley Group and located in the Arcata Bottoms.

Since the last meeting on this project, county staff talked with officials down in Santa Barbara County, where the smell-absorbing product is already in use, and they vouched for its effectiveness, Ford said. The applicants plan to use a combination of carbon scrubbers and a waterless vapor-phase system called Ecosorb to neutralize the skunky aroma.

The board had also asked staff to explore some additional conditions of approval for the project. These included more thorough odor-control measures; the dedication of a public easement for future trail development; another easement for the two parcels directly east of the project to preserve them as open space and/or an organic farm; and development of a solar system capable of providing all the power needed to operate the project.

Staff also modified an existing condition of approval, requiring Sun Valley to submit a “Neighborhood Odor Complaint Response Plan” to the county for review and approval.

As was the case three weeks ago, staff recommended denying the appeal of the Planning Commission’s approval of the project in May and approving eight total acres of greenhouse grow, including 5.7 acres of mixed-light cultivation and 2.3 acres of outdoor light-deprivation cultivation in enclosed, gutter-connected greenhouses — plus 30,000 square feet of ancillary propagation activities inside existing hoop houses.

After Ford’s staff presentation, Jim Cotton spoke on behalf of himself and the other appellants, saying that in their opinion the odor-control technology remains unproven and potentially dangerous.

“Bottom line is we don’t want to be a guinea pig for this [technology] until it’s been proven safe,” he said. He suggested the board go with an option proposed during the June 22 hearing by Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson and Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone — permitting just one acre of cultivation area and, if all goes smoothly, allowing a second acre after a year.

A series of speakers then weighed in on behalf of Arcata Land Company. Land use consultant Jordan Main argued that county staff and multiple outside agencies have vouched for the efficacy and safety of the odor-control technology.

“The proposed conditions [of approval] completely eliminate the possibility of an odor issue,” he said, adding that the additional measures, including the employment of a certified hygienist, “do more to address odor than any I’ve ever seen.”

Nearly two-thirds of the 29 public speakers voiced either outright opposition to the project or support for capping it at two acres. They expressed concerns about odor, air quality, public safety, declining property values and the market impacts of an industrial-scale cannabis operation.

Supporters who spoke focused mostly on the potential economic benefits while decrying what one man called the “NIMBY loudmouth group” that opposes the project.

The board took a 10-minute break after the public comment period, resuming deliberations around 3:40 p.m., and their ensuing discussion lasted roughly two hours. While odor was at least nominally the main reason for continuing the June 22 hearing, the board proceeded to discuss a wide range of issues, including noise, land use/zoning, the proposed easements, energy sources, toxic chemicals and much more.

Madrone was the first supervisor to lay his cards on the table. He argued that the applicant probably should have been required to prepare a full environmental impact report (EIR) rather than the less-comprehensive mitigated negative declaration (MND), but he nevertheless said he planned to stand firm with his support of a phased-in project starting with one acre, going up to two if all goes well.

Madrone also spoke about the importance of supporting the existing local “craft” cannabis growers rather than bulk producers who aim to supply the commodity market with consistent, if inferior, product.

Wilson reiterated a point he made at the June 22 hearing — that the land in question was slated to be rezoned from heavy industrial to agriculture-exclusive, and that the change would have been implemented if not for a lawsuit that halted implementation of the general plan update. That rezoning would have capped the weed grow at two acres, and thus Wilson felt two acres should be the limit.

Lane DeVries, the CEO and president of Sun Valley Group, was clearly frustrated, saying he thought odor was the topic at hand. He said he’d be willing to consider phasing in the project as long as phase one was 5.7 acres and phase two was the remaining 2.3.

First District Supervisor Rex Bohn made a motion to approve exactly that. He noted that the project was originally proposed at 33 acres before getting cut down to 22 and reduced again to eight.

“If we cut this half up any more, the baby’s out with the bathwater,” he said.

Bohn didn’t get a second on his motion, and the conversation veered into talk about the proposed trail easement and solar infrastructure.

After a while, Madrone inched toward some possible middle ground, saying he’d be willing to approve more than two acres — maybe up to three or four — if they were phased in slowly, ensuring that the neighbors weren’t negatively impacted.

From there, the conversation just got more convoluted. Wilson suggested a process whereby the board could consider amending sub-motions to the main motion on the table — that is, considering amendments pertaining to project details before voting on the primary motion pertaining to the whole project.

This suggestion only seemed to confuse people.

Bohn’s motion belatedly died for lack of a second, and Second District Supervisor Michelle Bushnell then took a stab, making a motion to approve a grow of up to 5.7 acres, phased in one acre at a time over multiple years.

Bohn seconded the motion for purposes of discussion, and there was no shortage of that.

Wilson made an impassioned pitch for requiring a dedicated easement on the land between the proposed weed farm and the nearby neighborhood, two large parcels of land that currently host an organic quinoa farm operated by Sun Valley.

But each of the other four supervisors had concerns of their own, and the discussion rapidly lost focus.

Fourth District Supervisor and Board Chair Virginia Bass made a few attempts to bridge the divide between her colleagues. Wilson stayed focused on the conservation easement. DeVries argued against being told what to grow on that stretch of land.

At one point, Bushnell turned to Wilson and asked whether his dogged pursuit of this easement proposition meant he was willing to vote “yes” on her motion, approving up to 5.7 acres of cultivation area.

“That’s a good question!” Wilson said with a smile. “Now you’re playing hardball!” He considered this quandary before saying that no, he was still not willing to support more than two acres. But he still considered the easement — preferably for an organic farm — very important.

Amid more confusion about the process and deliberations over the dimensions of the potential easement in question, Wilson wound up amending his amending motion. He modified his proposal to require not the entirety of the two parcels to be dedicated as an easement but just a portion of them — a 500-foot-wide swath along the eastern edge of of the project site.

DeVries said he’d feel a lot better about making all these concessions if the board were willing to permit the full eight acres he was requesting, and Bass made a comment suggesting she’d be willing to go for that.

Wilson balked. He said that if his proposal for a conservation easement was used as a vehicle to negotiate up to eight acres, “there’s no way.”

Eventually, the board got around to voting on Wilson’s amending motion. To clarify, they were voting on whether to attach a new condition of approval establishing a 500-foot-wide conservation easement directly east of the project site.

Madrone and Wilson voted yes; Bohn and Bass voted no; and after a dramatic pause, Bushnell voted yes. The amending motion passed.

Next it was time to vote on the main motion — whether to approve 5.7 acres of cultivation with all the conditions that had been added along the way.

Madrone called the decision “a tough one” and said he appreciated all the efforts to make the project more palatable, but 5.7 acres was just too big. He voted no, as did Wilson.

But Bass, Bohn and Bushnell all voted yes, and the motion carried. Sun Valley Group, which has been in the cut-flower business for decades, is about to diversify into the cannabis business.

CLICK TO MANAGE