Eureka police take an attempted murder suspect into custody earlier this year. File photo: EPD.

###

NOTE:

With an uncommonly crowded field of candidates for city council and

mayor in Eureka this year, the Outpost

is

taking a closer look at some of the city’s most significant and

oft-discussed issues, including economic development, needles, and, in this installment, crime and policing.

###

To hear the internet tell it, Eureka is going down the tubes.

Log on, and it’s hard to escape the anguish – whether it’s right here on the Outpost, or on Nextdoor.com, or on Facebook, where groups with names like “Eureka Neighborhood Defense,” “Humboldt Thieves” and others proliferate. If you’re looking, you can easily find fresh, up-to-the-minute evidence that the town is spiraling toward ruin, and it’s just as easy to find people who share your woe.

What’s causing Eureka’s decline? Petty thieves. Drug addicts. The homeless. The mentally ill. They choke our sidewalks and public spaces, frightening straight citizens and out-of-towners with their disheveled looks and odd behavior.

Things are only going to get worse, it seems, unless … something. Something must be done. The solution, we are given to understand, is maddeningly obvious, even if no one can quite articulate it. The general sense is that the malefactors must be “run out of town,” but specific proposals on how to accomplish this are thin on the ground. Certainly they must be denied services. Perhaps, some hint, they should also be knocked about a bit. The police must be “unleashed.”

STATE OF EUREKA

• As Candidates Promise Job Creation, Holmlund Says the City is Already in ‘a Renaissance’

• Following Citizen Outcry, the City is Ratcheting Up the Pressure on Needle Litter (and Hoping Things Won’t Snap)

• In Today’s Eureka, Policing is About Much More Than Arresting Bad Guys

But how much of this anxiety is due to actual, real-world conditions, and how much of it is a product of our unusually anxious age? Eureka has always been a rough-and-tumble place, and crime statistics suggest that it hasn’t become more rough and tumble recently. Rather the opposite: According to the numbers, property crime has been on a steady decline. Violent crime is currently higher than usual, but it’s far from off-the-charts high.

And to the degree that the city is still plagued by crime, how much of that is due to circumstances beyond our control – the opioid epidemic, a tight market for police officers, a jail at full capacity, changes to state laws on crime and punishment?

We’re on the eve of an election, and these topics – crime, homelessness, drug addiction, generally unruly citizens – are again somewhere near the top of the electorate’s mind. Many candidates for office have one of two stances on these issues – either “Things are getting better!” or “Things are getting worse!”

The Eureka Police Department isn’t going to bludgeon loiterers or drive them off to the city limits to be dumped on the other side of the line, no matter how much some dark corner of the Eureka psyche might pine for that. Those days are gone. You can get tough on crime up to a limit, but it’s not reasonable to urge police officers to break the law. It’s not a legitimate policy option.

“We want people to trust that we are working hard for the people of the city,” Eureka Police Chief Steve Watson said over coffee the other day. “We have a plan.”

###

What is actually going on with crime in Eureka?

The best indication we have — unfortunately — are the numbers that are reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigations Uniform Crime Reports program each month. Those numbers are published every year, with a bit of delay. (The FBI hasn’t published them for 2017 yet, so we requested them from the EPD directly.)

These numbers are broad and don’t allow us to drill down with much detail. Eureka police do keep track of every actual crime, and every call for service, that they get in a day. Most of those calls for service posted in near-real time right here on our PATROLLED page. But the Eureka Police Department recently switched its records management system; it doesn’t have old stats on — say — vagrancy or public alcohol consumption or the like.

On a per-capita basis, Eureka has always scored far higher than neighboring jurisdictions in the Uniform Crime Reports. (See this story from 2016, for example.) Part of this is undoubtedly due to Eureka’s particular qualities, but part is undoubtedly due to the fact that Eureka’s daytime population is far higher than its actual number of citizens.

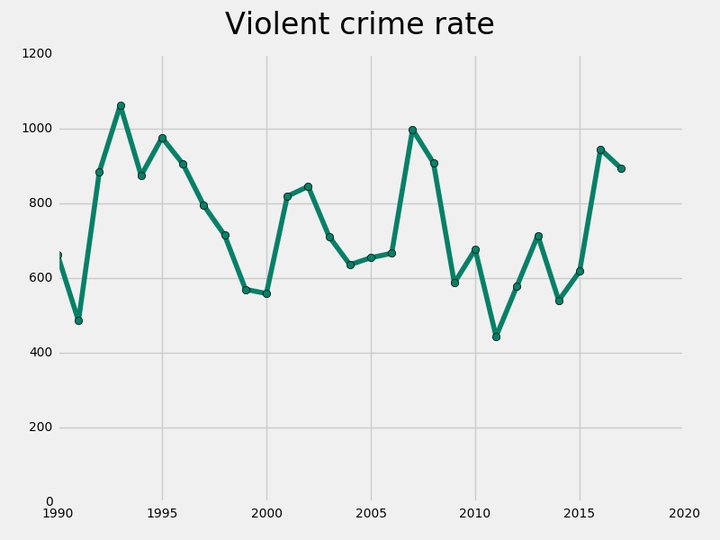

Eureka violent crime rate — homicide, rape, robbery and assault — from 2000 to the present. Graph represents number of incidents per 100,000 people.

Violent crime surged in 2016 for reasons that are unclear. Andy Mills, then the city’s police chief, laid it at the feet of the opioid crisis. But even that spike didn’t bust any records, and violent crime fell somewhat in the next year.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that an unknown but probably significant number of violent incidents — particularly aggravated assault, which account for the majority of violent crimes — occur between people who already know one another. The number of people randomly subjected to aggravated assault while walking down the street, minding their own business, is much smaller than these numbers would indicate.

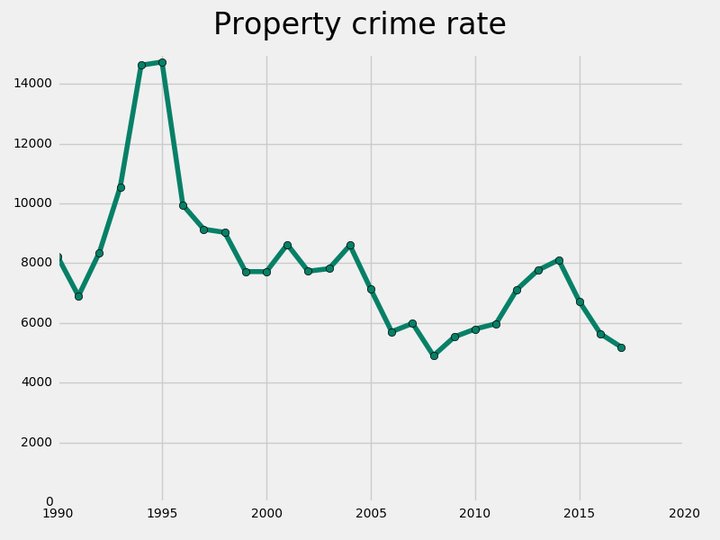

Meanwhile, property crime — theft, burglary and the like — occurs far more frequently than violent crime, and has been dropping steadily for some time.

Eureka property crime rate — burglary, larceny and motor vehicle theft — from 2000 to present. Graph represents number of incidents per 100,000 people. Click to make it bigger.

There are many things these numbers don’t reflect. Drunk-in-public calls, vandalism and other “lifestyle” infractions are nowhere to be found, here. But the best data we have indicates that we have less and less reason to worry about someone stealing from us.

###

What’s going on with policing in Eureka?

The Eureka Police Department employs detectives, an evidence technician, an analyst and a whole team — the Problem-Oriented Policing unit — whose mission is to identify and dig deep on particular sources of crime. The average Eureka police officer, though, still spends the great bulk of his time ping-ponging around the city in response to citizens’ calls to 911. The department averages over 150 calls per day — more than 6 calls in the average hour, or one every 10 minutes. There are usually no more than four or five patrol officers on duty at any given time. The job is to drive to a place, handle a situation, and make an arrest or write a report if necessary. And then to do it all over again, as quickly as possible.

A large number of those calls are for lifestyle crimes. They fall under a variety of headings — vagrancy, disturbing the peace, etc. — but the perpetrators are often guilty of nothing more than drug addiction, mental illness or homelessness. The police department is, by default, the front-line social services agency. When someone is standing at the Gazebo screaming at the sky, say, the police are going to get the call, even if no real crime is being committed. Even if you find some excuse to arrest such a person, they’re back out in hours, doing the same thing.

In recent years, the Eureka Police Department — under Mills and increasingly under Watson — the department has been partnering with other city and county agencies to urge people with such problems toward existing programs that can offer them help, and perhaps to actually solve the problem, or at least ameliorate it.

In early 2015, the department partnered with the county’s Department of Health and Human Services to found the Mobile Intervention and Services Team (MIST). Through MIST, beat cops who come into regular contact with a homeless person, or a person with other needs, are able to steer particularly problematic cases out of the criminal justice system and into treatment, or into a shelter. Last year, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that a number of people on the EPD’s “most contacted” list were reaching services through MIST.

The department launched another interdisciplinary effort — one that interfaces with MIST — earlier this year, shortly after the completion of the city’s Waterfront Trail. Called the “Community Safety Enhancement Team” (CSET), this new unit is meant to patrol and otherwise keep an eye on the city’s public spaces like parks and the waterfront. The CSET team includes one dedicated park ranger and another officer, along with support staff.

After the team arrested a man sleeping in Halvorsen Park (while allegedly holding a bunch of meth packaged for sale), Watson, on his Facebook page, offered a summary of its work to date. An excerpt:

Since the unit’s inception in July, CSET has removed approximately 17,115 lbs. (8 1/2 tons) of trash from our open spaces, made 153 arrests, issued 107 EMC citations for public offenses, and towed 28 abandoned autos. CSET has balanced these substantial (but needed) enforcement actions with significant outreach and engagement efforts among the homeless community while working collaboratively with the joint EPD-DHHS Mobile Intervention and Services Team (MIST). This has included linkage with services and arranging transitional and long term housing opportunities for several unsheltered homeless individuals. The team also connected several individuals with Waterfront Recovery Services in Eureka (a residential detox and substance use disorder treatment center).

The general thrust is to put people who need social services into the hands of social workers, so that police might get back more time to do more actual police work.

By himself, a police officer can’t do much for a homeless person walking down the street screaming at the sky. The only real card the officer has to play is to arrest that person, if the person can be found to be disturbing the peace. But the jail is often overcrowded, and the courts can’t do much to address this person’s issues, either — he’ll soon be back out on the streets, screaming more. Tomorrow, the same officer will be called upon to deal with the same offender, maybe in the same place. The police department’s bet — and the city’s as a whole — is that it’s better to patiently nudge such offenders toward people who have the resources and training to help them.

This is consistent with the city’s (officially adopted) “Housing First” approach to homelessness, and the interdisciplinary approach that the city increasingly has been using to tackle its biggest problems, or to accomplish its larger goals. In the last few years, after the mass evictions at the Palco Marsh, the city has been encouraging all sorts of efforts to put roofs over heads — the container village, a big Danco development, mother-in-law units. (The PG&E trailer village, which the city was set to approve a few months ago, was stalled after the owner of nearby Pierson’s Building Center threatened litigation.) More people in housing means fewer police calls to deal with homelessness.

Someone on city staff encouraged Los Bagels to put a bathtub flower planter in the alcove on the side of its old brick building at the corner of Second and E streets, where people had taken to loitering. (Development Services Director Rob Holmlund can’t remember if it was his idea or Public Works Director Brian Gerving’s.) Photo: Andrew Goff.

The department is also paying much more attention to design solutions to crime and other undesirable behavior. Earlier this year, more than a dozen city employees — several of them from the police department — completed a 40-hour course in a field called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.

The EPD had long offered citizen tips on how they could help secure their home with better fencing, or by making sure to remove newspapers from their porch, but lately the whole city has been paying much more attention to it. According to Development Services Director Rob Holmlund, he and several other city employees, including from the EPD, get together monthly to talk about particular problem spots, and how the city might work with business owners to ameliorate them using CPTED principles. This team also reviews new building applications to see if the developers’ plans might have unwittingly included crime-friendly design.

Miles Slattery, the city’s director of community services — the department that maintains the city’s public parks, trails, marina and neighborhood facilities — recently told the Outpost that he and the police department found common cause during the ongoing revamp of Highland Park, one of the city’s largest and previously most neglected. The police used some money from its asset forfeiture funds to help install lighting in the park — a cost-effective way to cut down criminal activity in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

“I think [Chief Watson] has a really good understanding that you can’t police your way out of these things,” Slattery said.

Watson himself lit up when asked to talk about new EPD efforts like these. To him, they point toward an exit ramp off the endless treadmill of doing nothing but sprinting between calls, dealing with situations as best you can, with no larger strategy in mind. And he said that it’s working.

“Creativity is a great word to describe what is happening,” Watson said. “And I love it. It gives you hope.”

###

To Watson’s mind, the Eureka Police Department’s biggest problem is also one of its oldest: It seems unable to ever get up to full staffing. New recruits — many of them fresh out of the local police academy at College of the Redwoods — are continuously lured away, often out of county, to police departments that can offer more money, better benefits, a calmer pace of life.

About this time last month, the EPD had three vacant positions for sworn officers, and was just about to lose two of its current officers to other jobs. At the same time, it was in the process of getting a former EPD officer back from a different agency, had one recruit from CR in the pipeline, and was doing background checks on an officer looking to move here from out of state. The department is continuously hiring. It hasn’t been at full staffing for a very long time.

Watson doesn’t think this problem is going to go away anytime soon, and a lot of it, he believes, is out of the city’s hands. Despite decent pay and good benefits, he says fewer and fewer people are looking to law enforcement as a career. (And this industry publication seems to back him up.)

But even though it may a tight labor market, the city is continuously tinkering with ways to position itself as a more attractive buyer. City Manager Greg Sparks told the Outpost a story about this the other day. Not so long ago, the city was down 10 sworn officers, he said. In an attempt to solve the problem, the city offered large signing bonuses to entice trained officers into making the leap to the EPD. It didn’t seem to garner much interest, so the city raised the bonus. And then it raised it again. A couple of people signed, but not enough to make a serious dent.

So they rethought the strategy. The bonuses might have attracted a few new officers, but it didn’t do anything to stanch the flow of EPD officers out of the department. So the city made a decision to discontinue the bonus, to freeze several positions that it didn’t look like the department was going to fill anyway, and to instead offer the rank and file a five percent raise, across the board.

It didn’t solve everything overnight, but city management is fairly confident that this little tweak — a more competitive salary — will pay dividends. This, in a nutshell, seems to be the city’s current approach to the problem, and to many others: Nothing is going to be fixed with the stroke of a pen, or a vote of the city council, but if we’re clever and we work hard we can make things a little better. And tomorrow we can do it all over again, and make it a little better still.

CLICK TO MANAGE