Eureka police officers take abatement actions to address code violations while people pick through the property collected onsite. | Photo: Andrew Goff.

Last Thursday around 8 a.m. Eureka police officers and city staff descended on a parcel on Bayshore Way to execute a criminal search warrant and take abatement actions on a variety of serious code violations. including illegally built structures, abandoned vehicles, stockpiles of garbage and debris, and makeshift communal latrines that had been draining human effluent into the adjacent wetlands, according to a press release.

The property had become a homeless camp, with nearly three dozen people living in various jury-rigged structures. They were given two hours to pick up and clear out in what was Eureka’s largest homeless eviction since the Palco Marsh was cleared out in May 2016.

The property itself was striking for its ornate professional landscaping — what remained of it, anyway. As we noted last week, one of the property’s homeless residents had given the Outpost a tour of the place barely 24 hours before the raid took place. We’d been reporting on volunteers in the countywide Point-in-Time homeless count who had set up in the Applebee’s parking lot across the street. (City staff says the timing of the raid the following day had nothing to do with the homeless census, though residents at the camp weren’t buying it.)

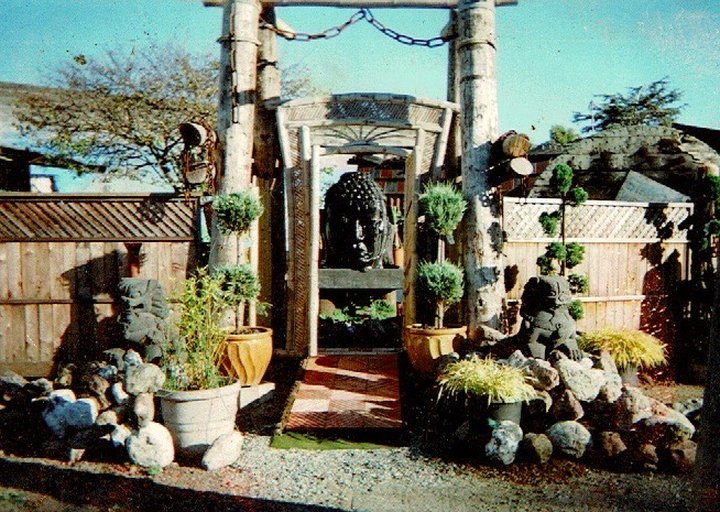

Photos from that tour:

A homeless man named Joseph giving a tour of the gardens on Bayshore Way last week. | Photo: Andrew Goff.

The garden was extraordinary, its mossy beauty and craftsmanship incongruous with the wasteland of chain stores and parking lots lining that southern stretch of Broadway. Turns out the garden was little more than a ruin, a neglected shadow of its former glory.

It’s been half a century since Ed Kirkpatrick bought this triangular parcel. The flat lot, just a block off the bustling freeway, sits wedged between a block of drab industrial buildings to the east and, to the west, a verdant greenbelt bordered by alders growing in a row atop an old railroad berm.

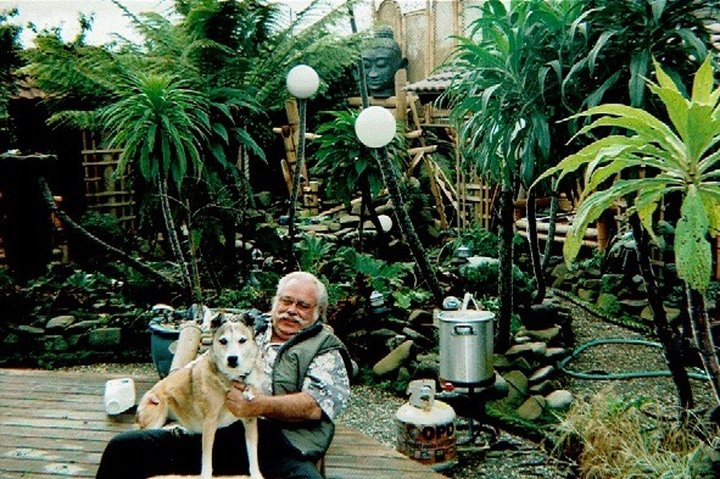

A retired landscaper, Kirkpatrick, now 77, spent years developing the property into what he calls “a spiritual garden,” a sanctuary that was capable, he says, of healing people and inspiring wonder.

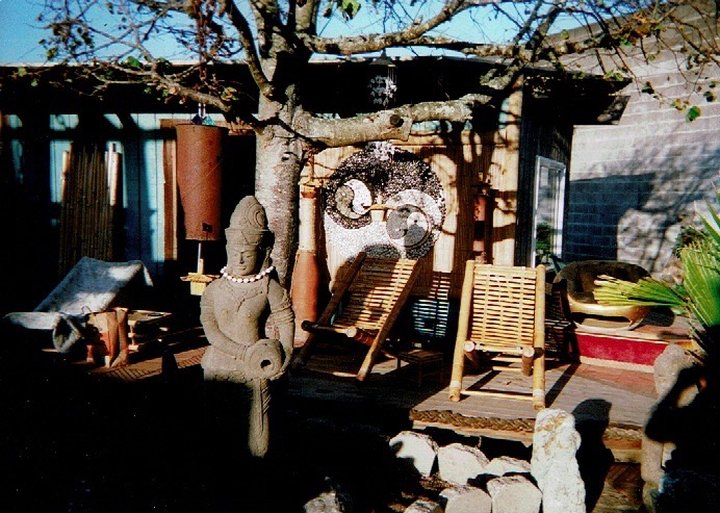

With careful planning, hard labor, and plenty of help from his utopian artist friends (Kirkpatrick was a contemporary of Hobart Brown, “glorious founder” of the Kinetic Sculpture Race), he built an elaborate ornamental garden complete with palm trees, bamboo structures, a mural of a tropical beach, and a little bungalow set amid the meticulously landscaped grounds, which he adorned with large-scale Buddhist statuary.

It looked like a Southeast Asian zen garden had somehow materialized on a gravel lot on the south side of Eureka, a lot that now sits wedged between an Applebee’s, a Taco Bell and the Bayshore Mall.

Photos in a dusty old album show the property in its heyday. We scanned a few:

There’s even one of Ed, looking happy amid the lush foliage with a canine companion on his lap:

Last Thursday, several hours into the City’s raid and demolition, this reporter picked Kirkpatrick up at his home in Eureka’s Henderson Center and drove him the 1.2 miles down to his Bayshore Way property. With his bushy white beard and wire-rim glasses he looks a bit like Santa Claus, and for the most part he has the jovial demeanor to match.

He was waiting to be picked up on the sidewalk outside his house, gripping a lacquered walking stick and accompanied by his tiny dog, a short-legged chihuahua named Taco.

Kirkpatrick consults his notes as he stands on property between his own and the Bayshore Mall. A mattress and accumulated garbage suggested that people had been living in the woods. | Photo: Andrew Goff.

Kirkpatrick explained that in recent years he’s been letting his friend Theresa take care of the property. A while back they allowed a few homeless people to stay there at night. Soon a few more showed up, followed by more still, with a big influx after the Palco Marsh evictions, and before long the situation got out of hand.

“You know what it is — they just bring stuff with ‘em and they never take it away!” he said on the drive to his property. “If I can teach ‘em to take it away I think I’ve accomplished more than anyone in the city.”

He’s had a number of ideas for the property over the years, but he’s been somewhat hamstrung by the zoning. He says the property was zoned commercial industrial when be bought it but was changed without notice to “upper wetlands” about 30 years ago.

City staff could not confirm the prior zoning, if any, and noted there’s no such zone in Eureka as “upper wetlands.” The parcel is currently zoned natural resources.

At any rate, in the late 1990s Kirkpatrick wanted to build some VA housing there. More recently he had the idea of creating a campground with tent cabins for cyclists traveling through Eureka. He also heard there might be grant money available for providing shelter to the homeless, and he met with city staff in late 2017 to see what he’d have to do to make the situation legitimate, turn the property into something along the lines of Betty Chinn’s container village. Kirkpatrick was tempted by the prospect of grant money to help pay his taxes, but he never followed through.

When we pulled up, Bayshore Way had been blocked off to traffic and Eureka police officers weren’t allowing anyone on the property. The sounds of heavy machinery were coming from behind a fence that Kirkpatrick had built without a permit.

Matt Morgan, Eureka’s code enforcement program manager, came out to the street to talk to Kirkpatrick.

“What’s happening in there?” Kirkpatrick asked.

“We’re abating the issues,” Morgan responded.

“Thank you,” Kirkpatrick said, sounding surprisingly chipper. He wanted a drive around to the other side of his property and he called to his little dog in a cartoonishly high-pitched voice: “C’mon Taco! C’mon my friend! … I do need to go in and see what those guys are doin’.”

An officer was stationed at the back side of the property, which is accessible via a path from the Taco Bell parking lot, but he wouldn’t let Kirkpatrick enter. So we meandered a bit through the woods, noting piles of garbage and an old mattress lying in the dirt. Kirkpatrick pulled out a spiral-ring notebook that included a rough sketch of his bike campground concept as well as bills he’s received from the City over the past year.

Kirkpatrick shows one of his monthly statements from the City of Eureka.

One was for $7,000 and change. Another was for $11,919.77. To date the fines and penalties had accumulated to nearly $20,000. “They keep fining me, and I keep tellin’ ‘em, ‘I’m doing the best I can,’” Kirkpatrick said.

Several times that afternoon he said he doesn’t blame the City; he understands that staff are just doing their jobs. But in other moments he voiced grievances.

“Why should they fine me? I’m helping the city, not hurting ‘em,” he said. “They should be cleaning this up anyway. … It’s not my problem; it’s the city’s problem to take care of these people.”

He hadn’t seen the City’s official justification, so I called up the press release issued earlier in the day by the Eureka Police Department and read it aloud:

“… conditions which pose a threat to public health and safety —”

“I agree,” Kirkpatrick said.

” … illegally built structures … electrical and fire hazards, accumulated garbage and debris —”

“Come and help me if you know all that!” he interjected.

“… abandoned vehicles in sensitive habitat —”

“That’s right. … When you get this element that’s what you get.”

So the press release was accurate?

“That’s exactly what’s happening down here,” Kirkpatrick said. “I can’t blame the city. All those things they say, you go back there, you’ll see ‘em.”

But this sanguine attitude didn’t last. By the next day, after he’d seen how his property looked post-demolition, Kirkpatrick was accusing the City of “raping” his gardens, stealing his belongings, and failing to treat him with humanity. At one point, according to city staff, he had to be escorted from his own property.

# # #

Many of the people who’d been living amid Kirkpatrick’s bamboo and statuary were chronically homeless. Several who the Outpost spoke to last week had lived in the camps at Palco Marsh, aka Devil’s Playground, before being evicted. One of them, Jack Sarter, subsequently moved into the former Mycroft Supportive Care facility in Eureka’s Pine Hill neighborhood.

The facility quickly became overrun with squatters and abandoned vehicles, and neighbors were soon up in arms over the noise, crime and refuse. The situation led to heated community meetings organized by Supervisor Rex Bohn and a court battle that led to another round of evictions.

Nearly three years after the Palco Marsh evictions, Eureka’s struggles to address the homelessness crisis don’t appear to have made much headway. The results of last week’s Point-in-Time count probably won’t be released for several weeks, but it’s clear to anyone living and working in Eureka that many people are still living on our streets, in cars and alcoves, and out in the elements during the coldest and rainiest period of the year.

Last Thursday evening, the day after the evictions at Bayshore Way, Sarter and some friends sat on the curb next to Kirkpatrick’s illegal fence. A young puppy lay sleeping at their feet. None of them knew where they’d sleep that night.

“I got $55 but it’s not enough for a motel room,” Sarter said. The cheapest one in the city is $73, he said, so he’d have to wait until getting paid two days later. The two women he was with said they didn’t know where they’d sleep, either.

In the bright light of the following morning, people walked across the muddy tractor tracks and picked through the piles of stuff that had been gathered between a shipping container and a large dumpster: clothes, tools, bicycles, plastic totes, lawnmowers, a barbecue, an American flag. It was all heaped next to some of Kirkpatrick’s garden statues.

A man who gave only his first name, Darren, said he’d been living there for six months, his friend for two years, and the two of them had tried to keep things nice.

“But we couldn’t watch the gate 24 hours a day, so people started moving in and nobody was able to tell who lived here and who didn’t live here,” he said. “Literally like overnight tents are popping up, and with that comes the people and the characters, the stolen property. We tried the best we could to keep the people from coming and going and doing what they were doing, but it was a little overwhelming.”

Darren was picking things up and putting them into a plastic tote. “This is my stuff,” he said. “We were trying to get it all picked up and figure out what we were gonna do. There wasn’t any kind of notice. It was like, ‘You’ve got a couple hours to pick up and get out.’”

Photos: Ryan Burns.

In one pile of property, next to the decapitated head of a terracotta Buddha, lay a rusty metal sign for Kirkpatrick’s old landscaping business.

Darren looked around at the property, the bulldozer tracks and litter, the massive Buddha head behind fluttering red caution tape. City personnel had already hauled off more than 640 cubic yards of debris from the property.

“We didn’t do this. We did not do this,” Darren said. “We had our stuff put away in camps. And the camps may look like camps; they didn’t look like condominiums. But this” — he gestured around — “was not how we were livin’. My stuff was neat. I had everything put away and clean.”

If so, he was the exception to the rule, according to Eureka Public Works Director Brian Gerving. After attempting for more than a year to get Kirkpatrick to address the issues on the property, the situation had become dangerous. Not only did crime and stolen property radiate from the site, but there were safety concerns, too. Some the unpermitted structures were dilapidated, had been outfitted with makeshift, generator-powered electrical systems, “and inside, just an overwhelming stench of urine and feces,” Gerving said.

He and other members of city staff met with Kirkpatrick before the “formal enforcement actions” of last Thursday to discuss the problems and try to develop options, Gerving said, but Kirkpatrick didn’t respond. Nor had he responded to the notices of violation and fines sent via mail over the past year. Gerving said Kirkpatrick will be charged for last week’s enforcement actions, including the costs of staff time, equipment and disposal. That hefty bill will be added to Kirkpatrick’s $20,000 in outstanding fines, and if he’s unable to pay, the City will place a lien on the property.

Gerving said such fines are a last resort.

“The only reason they ever are issued in the first place — or continue to accrue to the extent that they did in his case — is that people ignore those enforcement actions.”

As to the extent of the destruction, Gerving said, “The inspection and abatement warrant authorized us to take any means necessary to resolve those violations, and the only reasonable way to do that was to demolish the structures.”

And what about the people who’d been living there? Why not give them — or Kirkpatrick, for that matter — more of a heads up before descending on the property en masse and allowing just two hours to clear out?

Gerving said the City’s actions vary based on the situation but the warrant in this case didn’t require any notice. In previous evictions, such as the Blue Heron and Budget motels, extra people moved in after eviction notices were served because they heard the city would be providing vouchers or money, Gerving said. It just made the eviction process more complicated.

The City offered no such vouchers to the former residents at Bayshore Way.

There’s some disagreement between Eureka staff and the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) about how the evictions were carried out. Gerving said that “the plan” had been for MIST, the county’s Mobile Intervention Services Team, a collaborative initiative with the Eureka Police Department, to be at the site on Thursday when the initial contacts with residents were made.

“As it turns out,” Gerving said, “those county staff didn’t come.”

County staff pushed back on that claim. In an emailed statement, DHHS Public Information Manager Heather Muller said, “DHHS Mobile Outreach was informed of the eviction shortly before it began. MIST was not contacted. There was never a ‘plan’ on DHHS’s part to be there. DHHS is not in the eviction business, and we’ve learned from past events that our presence during sweeps and decampments can obscure that fact.”

DHHS staff was familiar with most of the people who’d been living on the property, and they decided to reach out later, away from police presence, to help them find housing, Muller said.

DHHS Director Connie Beck also expressed concerns about the timing of the evictions. Last Thursday, the day of the enforcement actions, she issued a statement saying, “I hope today’s evictions will not have a chilling effect on participation in future PIT [Point-in-Time] counts. A full and accurate count is critically important for us to receive the funding we need to address homelessness in Humboldt County.”

Eureka City Manager Greg Sparks said the City is continuing its efforts to provide transitional housing, building off the progress made by Betty Chinn’s container village at Washington and Koster streets. The City provides roughly half of the $150,000 required annually for 24-hour management of that site, which has the goal of finding residents employment and more permanent housing within 90 days of moving in.

The City hopes to establish a similar and complimentary model with trailers donated by PG&E. Sparks said staff is finalizing a site plan for a parcel on Hilfiker Lane and hoping to meet with adjacent property owners later this month.

“We have funding from the county to put in water, sewer, and other improvements at the site,” Sparks said. Once up and running, the trailers will be able to house about 50 people at a time.

Meanwhile, the City is still trying to figure out how to implement a 2018 ruling from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which found that banning homeless people from sleeping outdoors on public property when there’s no other shelter available is effectively criminalizing homelessness and, in some cases, may violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

The City is also developing a smartphone app that will show where shelters are available. Homeless people may not have smartphones, Sparks admitted, but Eureka police officers and other service providers certainly will.

Such measures may help, but with the region’s dearth of affordable housing, plus the high incidence of mental health and substance abuse issues, progress on the homelessness crisis continues to be slow.

# # #

Last Friday, shortly after the sun had gone down, Kirkpatrick walked unsteadily, sans walking stick, through the muddy tractor ruts on his Bayshore Way property. Perusing the wreckage of his garden he seemed to vacillate between grief, anger and a sort of Zen Buddhist detachment.

“If I’d have died yesterday it would have happened anyway,” he said.

He glanced at the giant Buddha head. He’d constructed an “observatory” in a van that was camouflaged on the south side of his property, a place where he’d sometimes sleep overnight and observe the homeless. That had been torn down.

“The City, you can tell, they ripped it apart,” he said. “I mean, they had to in one manner, but I really feel that the City has an agenda and wants to steal my property away from me.”

He spun around, looking in one direction and another. A 12-foot-by-20-foot shed was gone, he observed. There was the sound of an engine revving, and in the fading twilight Kirkpatrick saw a pickup truck peeling out, spraying mud from its back tires before it gained tractions.

“Oh, where are you goin’?” Kirkpatrick said. He flashed with anger. “What a jerk! GET THE HELL OUTTA HERE!” He started tottering toward the moving truck, searching the ground as he went. “Goddamnit. When I find a rock you’re gonna get it.”

He approached the truck as it was picking up speed and yelled again: “GET THE FUCK OUTTA HERE! Son of a bitch! WHAT THE HELL’S WRONG WITH YOU? STICK YOUR HEAD UP YOUR ASS, BUDDY!”

The truck pulled away, turned right on Bayshore and drove off.

“Damn,” Kirkpatrick said as he regained his composure. “See? I’m not supposed to yell. This isn’t the place to yell. You know, I’ve been yelling more than I ever have in my whole life, and I sound like my brother when he used to yell at my mom … . Oh, he used to yell at her and I’d say, ‘Oh, you can’t do that.’ But that’s the way I sound. And I don’t wanna sound that way. But this is a real nightmare.”

This property used to have a spirit to it, he said. It was his sanctuary, his summer vacation retreat, a place to gather with friends or just sit with his dog and bask in the energy. Some of the homeless people didn’t feel or appreciate that spirit, he said, and their abuse of the place made some of it disappear. He doesn’t think city staff felt it either, and they tore more of it away.

Last week, Kirkpatrick stood in the gardens he’s built in the backyard of his home in Henderson Center. They, too, are elaborate and lush, with huge statues and bamboo benches. Kirkpatrick wore a silk kimono and, looking calm once again, he talked about his past: his childhood growing up with an “alcoholic tyrant” for a stepfather, his own struggles with alcoholism, his reverence for his mother, who he considered a healer.

He’s still angry at the City, and he talked idly about maybe suing them. But he also spent time on his bamboo bench, eyes closed, listening to the wind rustle through the palm fronds and the sounds of traffic on the streets of Eureka.

Kirkpatrick’s backyard garden.

CLICK TO MANAGE